by Robert K. Fitts

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Rob Fitts writes about how Lefty O’Doul brought a MLB all-star team, featuring Joe DiMaggio, to Japan in 1951.

In 1951 American troops still occupied Japan, but their mission had shifted. Rather than seeing the country as a former enemy to be subjugated, Japan was now viewed as an ally in the fight against communism. As the war in Korea raged, Japan became a strategic center for United Nations troops, providing a supply base, command center, and behind-the-lines support that included hospitals. It became vital to US policy that democracy flourish in Japan and that ties between the two nations remain strong.

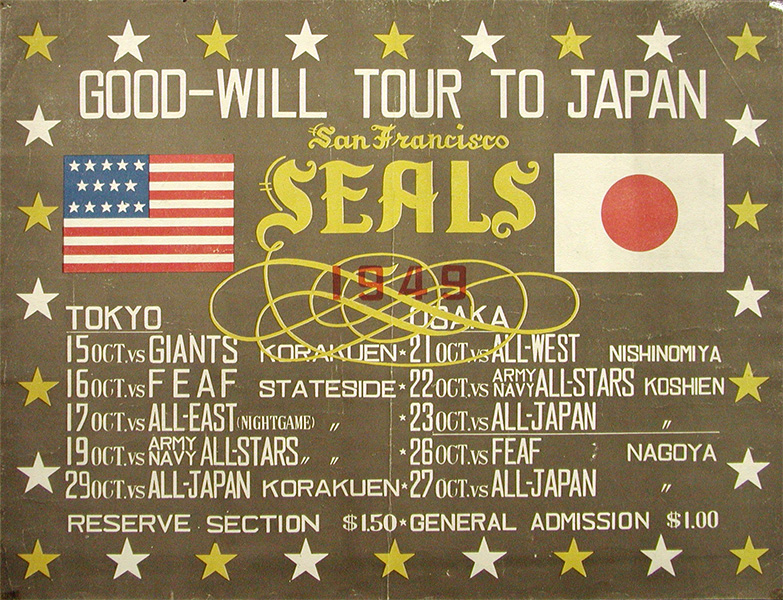

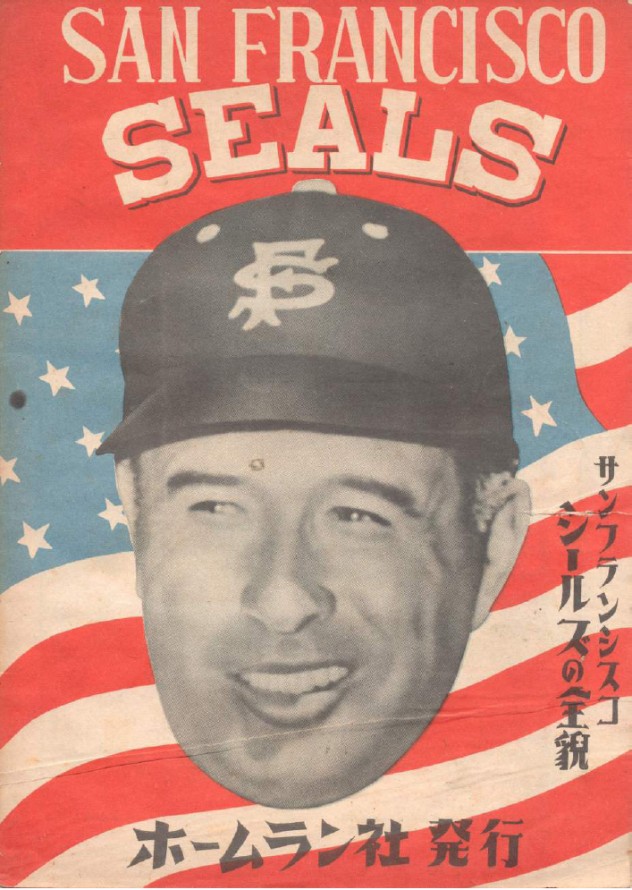

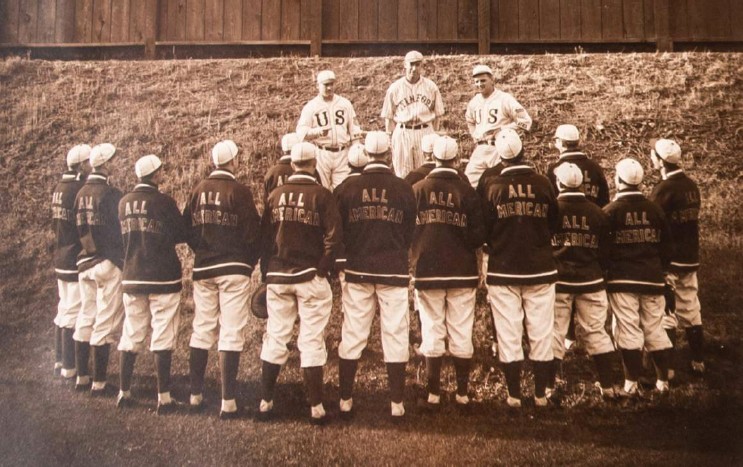

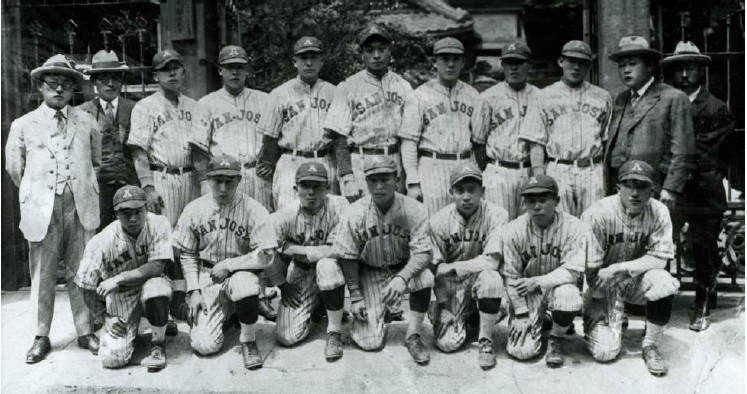

Since the end of World War II, US forces had consciously used the shared love of baseball to help bind the two nations together. To this end, Maj. Gen. William F. Marquat, the occupation forces’ Chief of Economic and Scientific Section, had restarted Japanese professional and amateur baseball immediately after the war. He also worked closely with Frank “Lefty” O’Doul to organize baseball exchanges. O’Doul made three trips to Japan between 1946 and 1950, bringing over the San Francisco Seals in 1949 and Joe DiMaggio in 1950. In August 1951, O’Doul announced that after the season he would return to Japan for the fourth time; this time taking an all-star team of major leaguers and Pacific Coast League stars on a goodwill tour to bolster ties between the two countries.

Sponsored by the Yomiuri newspaper, and organized by Sotaro Suzuki, the team was to play 16 games during a four-week trip starting in mid-October. The roster included American League batting champ Ferris Fain, Bobby Shantz, and Joe Tipton of the Athletics; Joe DiMaggio, Billy Martin, and Eddie Lopat of the Yankees; Dom DiMaggio and Mel Parnell of the Red Sox; Pirates Bill Werle and George Strickland; and PCL standouts Ed Cereghino, Al Lyons, Ray Perry, Dino Restelli, Lou Stringer, Chuck Stevens, and Tony “Nini” Tornay. To accommodate the All-Stars’ schedule, Japanese baseball Commissioner Seita (also known as Morita) Fukui canceled the final games of the Nippon Professional Baseball League so that the Japan Series could be concluded before the all-stars arrived.

As the all-star squad was about to depart, Joe DiMaggio made a stunning announcement. He was considering hanging up his spikes. In a meeting in New York, Yankees President Dan Topping supposedly told his star, “You are going to Japan. … You will have a lot of time for thought. So, think it over, and when you get back to New York, call me up and we will go over this matter again.”

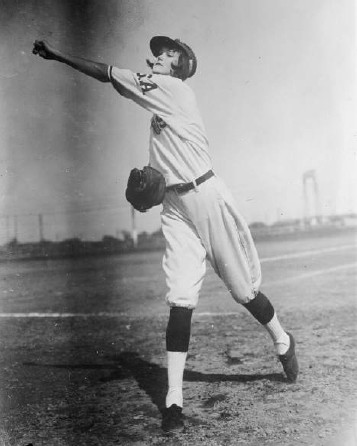

O’Doul’s team gathered in San Francisco on October 15 and the next day boarded a Boeing 307 Stratoliner for the long flight to Hawaii. After an hour’s delay before takeoff, the plane finally departed. Thirty minutes later, an engine began to sputter and then died. “Boy, was I scared,” recalled Bobby Shantz. “It’s no fun to have a motor conk out and see nothing below you but Pacific Ocean!” The Stratoliner returned safely to San Francisco and after three hours of repairs tried again. As the plane neared Hawaii, O’Doul told his players to change into their uniforms. The team was scheduled to play a 7:30 P.M. game in Honolulu and although they would be late, Lefty planned to keep the engagement.

Once they touched down at 9:45 P.M., a police escort whisked the ballplayers to Honolulu Stadium, where 15,000 fans were still waiting for the visitors to arrive. By 10:30 they were playing ball. The exhausted All-Stars put in a poor performance against the local semipros. The Hawaiians scored six off Shantz and Lopat as starting pitcher Don Ferrarese (who had played minor-league ball and eventually had an eight- year major-league career) held the visitors to a single run in four innings before the All-Stars erupted for five in the fifth inning to tie the score. Reliever Ed Correa, however, stymied the All-Stars for the remainder of the contest, striking out eight, as the Hawaiians pushed across two more runs to win 8-6. To the great disappointment of the crowd, Joe DiMaggio did not start and only appeared as a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning -Correa fanned him on three pitches. One irate fan later wrote to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

Do you honestly think that the way you let 15,000 people down the other night is true sportsmanship? Folks came piling into the Honolulu stadium at7:00 PM and waited for six hours. … They came in droves, young and old. Old women carrying babies, dads with their kids, who should have been in bed in order to be ready for school the next day. And for what? … they all came for the one purpose of seeing one man in action, Joe DiMaggio. All through the game an old grandmother sat holding her grandson, who kept asking, ‘Where’s DiMaggio, Gramma, where’s DiMaggio? And when he finally did appear for an instant in the 8th, I looked over at them, and they were still waiting there, sound asleep! Yep, Lefty, you sure let us down.

After the game ended at 12:55 A.M., the All-Stars trudged back to the airport and boarded a flight to Tokyo.

General Marquat met the team when it arrived at Haneda Airport at 4:30 P.M. After a brief press conference, Marquat ushered the players into 15 convertibles for a parade through downtown Tokyo.

As dark fell, nearly a million fans lined the streets of Tokyo to welcome the team. “I never saw so many people in my life,” recalled Shantz. “Baseball worshipping Japanese fans choked midtown Tokyo traffic for an hour and rocked the city with screams of ‘Banzai DiMaggio!’ … in a tumultuous welcome,” the United Press reported.“Magnesium flares flashed through the sky as the motorcade inched through the mob. DiMaggio and O’Doul were in the lead convertible, just behind a Military Police jeep that used its hood to push back the mob to clear a path. ‘Banzai DiMaggio! Banzai O’Doul!’the mob shouted. Scraps of paper rained from the windows of office buildings.”

Yets Higa, a Honolulu businessman who accompanied the team to Japan, said, “The cars finally slowed down to almost a snail’s pace as thousands of Japanese baseball fans walked right up to the cars to touch the celebrities from America. The crowd intensified its enthusiasm as an American band played Stars and Stripes [Forever]. The whole thing was so fantastic that I couldn’t believe my eyes. Never in my life have I seen such a tremendous welcome given to any team.” The “surging crowds gave the ball players one of the greatest receptions ever accorded any visitors to Japan,” added the Nippon Times}

The next afternoon, Thursday, October 18, 5,000 spectators showed up at Meiji Jingu Stadium (renamed Stateside Park by the occupation forces) to watch the visiting ballplayers practice. O’Doul and DiMaggio remained the center of attention. “When O’Doul walks off or on the field, going to his car, walking to the locker room or any other time he appears in public, people seemed to spring right out of the ground. Baseball fans of all ages press in on him and beg for an autograph or just mill around, trying to catch a glimpse of ‘Refty.’ Joe DiMaggio is the same way. … It becomes almost impossible for him to move from one place to another for the people who want him to sign cards, baseballs, scraps of paper, old notebook covers or anything they happen to have handy.”

That evening more than 3,000 fans jammed the Nippon Gekijo, Asia’s largest movie theatre, to see the ballplayers. Thousands more waited outside after being turned away from the sold-out event. During the brief ceremony, Sotaro Suzuki introduced the players as each stepped forward and bowed to the audience. After the introductions, O’Doul spoke: “The long war with cannons and machine-guns is ended. Let’s promote Japanese-American friendship by means of balls and gloves. There is no sport like baseball to promote friendship between two countries. Oyasuminasai [goodnight].”

On October 19, after 10,000 fans came to watch them practice, the ballplayers met with Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, commander of the United Nations forces in Korea and the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan. The general told the team that he was “very happy the major leaguers had come to Japan and felt sure their visit would promote good relations between the United States and Japan.” Ridgway also asked if the squad could travel to Korea to entertain the troops.

The gates of Korakuen Stadium opened at 8 A.M. the following day to accommodate the expected throng for the opening game against the Yomiuri Giants. The players themselves arrived for practice at 11:40. By 1:30, 50,000 fans packed the stands as baseball comedian Johnny Price began his show. Often known as Jackie, Price had been a longtime semipro and minor-league player (with 13 major-league at-bats for the Cleveland Indians in 1946), who had turned to comedy. During the 1940s and ‘50s, he performed at minor- and major-league parks across the United States. His act included accurately pitching two baseballs at the same time, blindfolded pitching, bunting between his legs, catching pop flies down his pants, and both playing catch and batting while hanging upside down by his ankles from a swing set. His signature act featured shooting baseballs hundreds of feet in the air with an air-powered “bazooka” and then catching them from a moving jeep. The Japanese fans adored the show, having never seen anything like it in their serious games.

At 1:45, an announcer introduced the two teams and numerous dignitaries as they lined up on the field. Just as the pregame ceremonies and long-winded speeches seemed endless, General Marquai yelled, “Let’s get on with the ball game!” and a few minutes later the teams took the field.

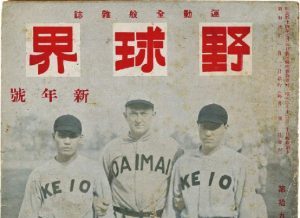

The Yomiuri Giants had just completed one of their most successful seasons, running away with the Central League pennant by 18 games and then topping the Nankai Hawks in the Japan Series, four games to one. Their star-studded roster included seven future members of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. Nevertheless, “manager Shigeru Mizuhara readily admitted that his championship team didn’t have a chance, but he promised his ball players will be hustling all the way to put up a good fight.”

It did not take long for the All-Stars to grab the lead. After starter Takehiko Bessho retired leadoff batter Dom DiMaggio on a fly to right field, Billy Martin beat out a grounder to the shortstop. Ferris Fain then stroked a line-drive single into center field, sending Martin to third. Joe DiMaggio stepped to the plate and on a 2-2 count, “answering the fervent pleas of the fans” slammed a sharp single by the third baseman to score Martin. But a nifty double play turned by second baseman Shigeru Chiba ended the inning.

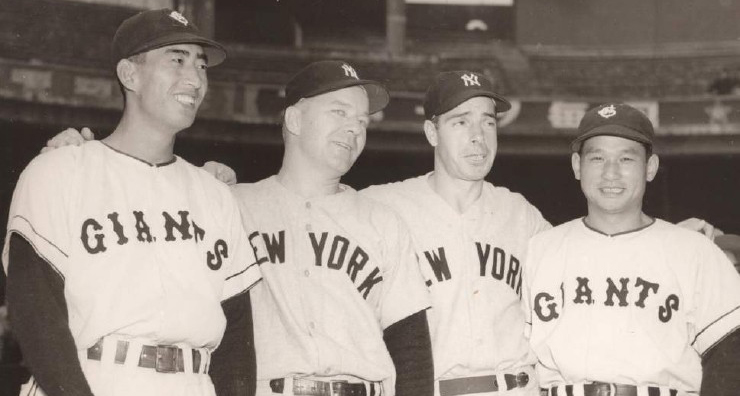

Leading off the bottom of the first for Yomiuri was Lefty O’Doul’s protégé Wally Yonamine. Yonamine was the first American star to play in the Japanese leagues after World War II. Frustrated by not reaching the inaugural Japan Series in 1950, Yomiuri executives wanted to import an American player to strengthen their lineup and teach the latest baseball techniques.

They reasoned that hiring a Caucasian player so soon after the end of the war would lead to difficulties, so instead they searched for the best available Japanese American player. They soon settled on Hawaiian-born Yonamine, who had not only just finished a stellar year with the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pioneer League but had also become the first man of Japanese descent to play professional football when he joined the San Francisco 49ers in 1947. In his first season with Yomiuri, Yonamine became an instant star, batting .354 with 26 stolen bases. He went on to have a 12-year Hall of Fame career in Japan.

Yonamine battled starter Mel Parnell before drawing a walk. With a one-out single by Noboru Aota, the Giants threatened to even the score, but Parnell got out of the jam and proceeded to shut down Yomiuri for the next five innings. In the meantime, Bessho retired the next 10 All-Stars and the fifth inning began with the score still 1-0. Two errors, a walk, and a single in the fifth, however, increased the All-Stars’ lead to 4-0. The Americans tacked on another three runs and Bill Werle came on in relief of Parnell, holding Yomiuri scoreless for the 7-0 victory.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website