by Bill Maloney

Victor Starffin was more than a great pitcher. He wasn’t just a Giant on the field, but also a giant off the field. The first 300 game winner in Japan amazed baseball fans all throughout his career, from his amateur days as a young teenager, wowing crowds in Asahikawa, to the end of his career, winning his 300th game with the Tombo Unions. Since his career and his tragic passing at the age of 40 years old, Starffin’s legacy as a ballplayer has been well documented and known.

However, due to his early passing, his two daughters, Natasha and Elizabeth, sadly did not have much time with their father. As a mother, while watching her children at play, it dawned on Natasha that her father had passed away by the time she was their age. Up until then, she had known about his achievements but, she says, “didn’t really care who he was.”

At its essence, the film Tokyo Giant: The Legend of Victor Starffin is about Natasha and Elizabeth connecting with their father all these years later, as well as reuniting with each other after over four decades. The film speaks to the unending bonds of family across centuries, wars, and oceans.

It shows Japan as the nation grows into an international power, following its Westernization, industrialization, and victory in the Russo-Japanese War. During this time, Japan and the U.S. gradually inch towards war, with hostilities increasing, despite their mutual admiration for each other, which was on display during the 1934 American League All-Star team’s tour of Japan.

Starffin’s family fled Russia during the violent, ghastly Russian Revolution. Victor’s father was an officer in the army of Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia, and bribed the drivers of carriages full of frozen corpses to let them hide amongst the corpses so they could escape the Red Army. The Starffins initially settled in Harbin, located in Manchuria, before emigrating to Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost prefecture, as refugees and the only Russians in their new city of Asahikawa.

Japan had recently started accepting refugees because of international pressure from nations criticizing them for not doing so. A little over ten years before Starffin was born, Japan defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War and agreed to the Treaty of Portsmouth. For his notable contributions in brokering the treaty between Russia and Japan, President Theodore Roosevelt became the first American to win a Nobel Peace Prize. Japanese leaders were denounced for what were perceived by the Japanese people to be the treaty’s lenient terms.

Tokyo Giant: The Legend of Victor Starffin captures the increasing hostility that foreigners in Japan, known as gaijin, faced. Victor was bullied as a kid and sports was the only way he could make friends and get along with his classmates. Because of his size and strength, he was seen as a leader. Even though he was the greatest pitcher in Japanese history, his daughters also experienced the same anti-foreigner sentiments. Due to this mistreatment, after Elizabeth left Japan in her youth, she did not return for forty-three years, when she returned for the filming of this documentary.

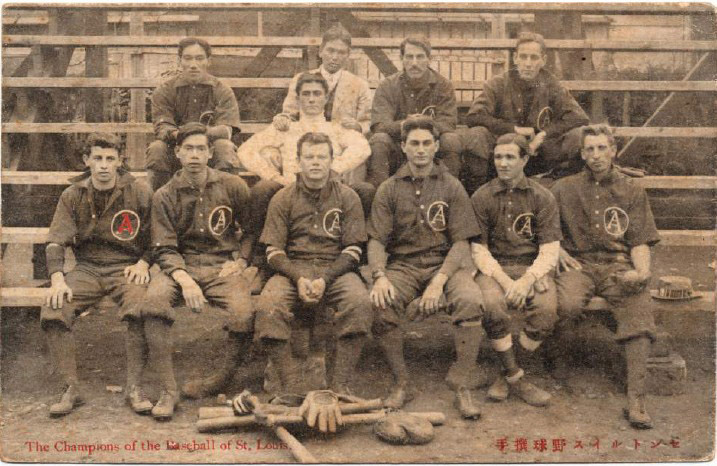

Starffin was a prodigious baseball talent during his youth, with his goal being that of winning the Summer Koshien baseball tournament. When Matsutarō Shōriki, the owner of the Yomiuri Shimbun, was forming a baseball team to compete against the 1934 American League All-Stars, he invited the high-school pitcher to join the team, but Starffin declined to. At the time, the elder Starffin was imprisoned after killing his lover, a Russian girl who worked at the family’s teahouse. Initially, he claimed it was a crime of passion, but later accused her of being a Soviet spy. Shōriki, who previously was the chief secretary of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, heard about the father’s crime and blackmailed Victor, saying that if he didn’t play for his All-Nippon team, then the Starffin family would be deported back to Russia, which, as it was then controlled by the Soviets, would be a death sentence for the family. Having no choice, Starffin joined Shōriki’s team.

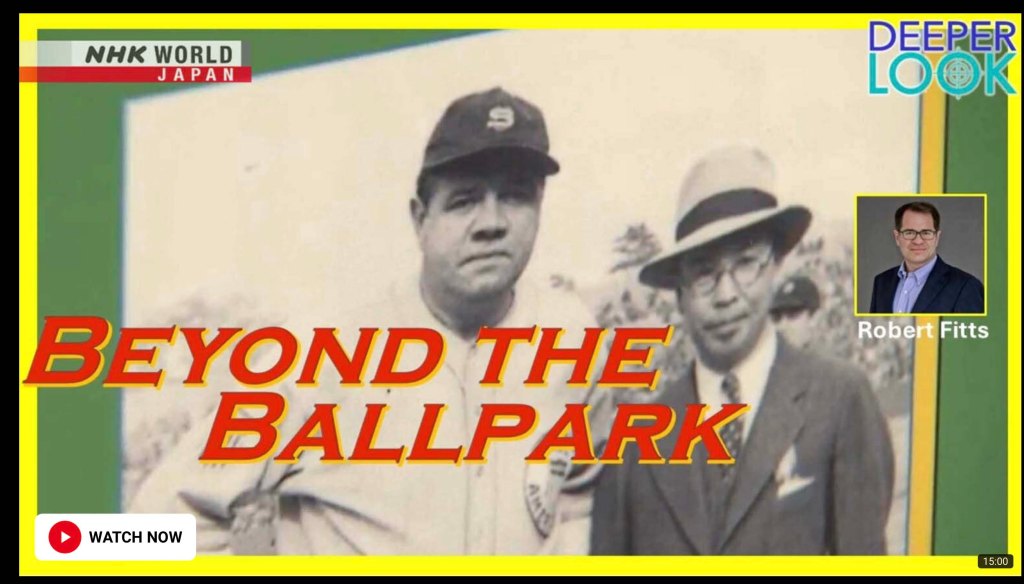

The 1934 All-American tour of Japan was years in the making, with Shōriki spending years trying to persuade Babe Ruth to come to Japan to play there. What convinced “The Sultan of Swat” to entertain the Japanese fans with his thunderous home runs was that he was to be celebrated as “The King of Baseball,” which was particularly important to him as he was at the very lowest of his career. Joseph Grew, the American ambassador to Japan, said “Babe Ruth… is a great deal more effective Ambassador than I could ever be.” Ruth’s family, including his adopted daughter Julia Ruth Stevens and granddaughter Linda Ruth Tosetti, make appearances in the documentary, providing insight about the tour and commentary about a parallel in Ruth and Starffin both being dissatisfied with how their careers ended.

Whereas the Americans perceived baseball to be a game that should be leisurely enjoyed, the Japanese viewed it as a training for the harsh battles of life. The games against Ruth and his fellow all-stars were about more than baseball. They were about national pride. Japanese fans thought that if they could beat Americans in their game of baseball, then they could also be victorious against them in other arenas.

The tour upset Japanese nationalists. One stabbed Shōriki for being “unpatriotic” for bringing Babe Ruth and other American ballplayers to Japan. After the All-Nippon team became Japan’s first professional baseball team following the tour, many more Japanese fans were upset. Professional baseball was seen as not pure and a “freak show.” When the team played at Meiji Jingu Stadium, near the shrine where Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken are worshipped, they were seen as committing sacrilege and defiling the area.

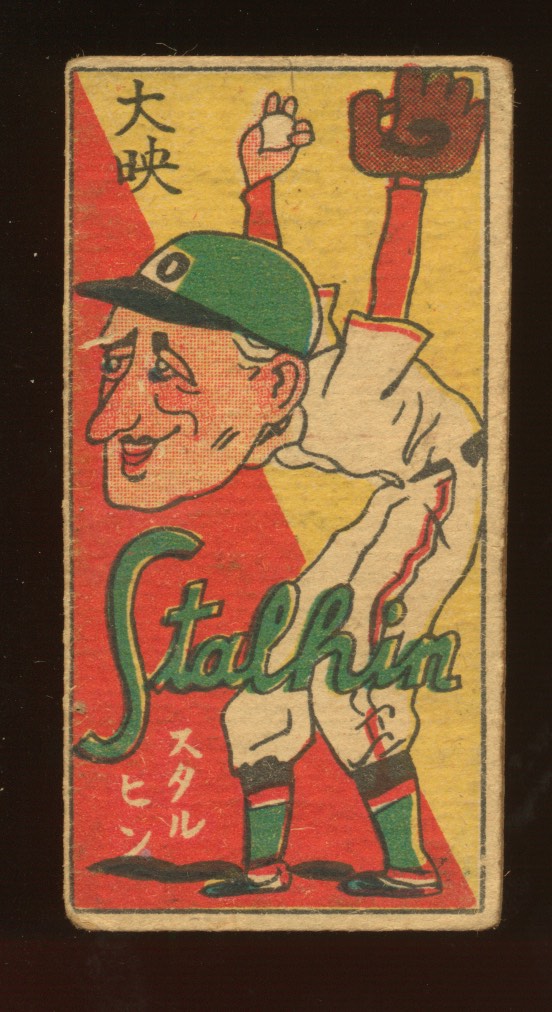

It is painful to see how Starffin and his daughters were so mistreated. He was suspected of being a spy and even had to change his name, which his daughters point out in a heartbreaking scene where they show league most valuable player awards he received in consecutive seasons while playing for the Tokyo Giants, one referring to him as Victor Starffin while another uses the name of Suda Hiroshi, a name he adopted when he was forced to use a Japanese name in order to continue playing. During World War II, he was sent to a detention camp.

The film’s highlighting of the discrimination and persecution that Starffin faced helps the viewer understand the spirit that he brought to the ballpark as he marched towards 300 wins as a member of the Tombo Unions, a new ballclub full of aged players. Japanese baseball historian Masaru Ikei says that “he might have been burning off his resentment from his wartime oppression.”

Interviews with former friends, classmates, and teammates of Starffin’s illuminate the person behind the astounding pitching. It’s heartening to see each of them share their warm memories of him. Starffin Stadium in Asahikawa is the only municipal stadium named after a private person in Japan. Yasuyuki Takakuwa, a childhood friend of Starffin’s, was so inspired by his friend that he worked to get the stadium named after him.

This documentary is about more than just Starffin himself. It is about a family reuiniting with each other. Natasha and Elizabeth, separated since they were young, come together with each other, their father, and other family members. Elizabeth says “I know who he[, my father,] is now, what kind of a person he was, and [that] makes him, in my mind, a lot bigger of a person.” Their cousin, Oleg, who Elizabeth visits in her father’s birthplace of Nizhny Tagil, a city slightly east of the Asia-Europe continental border, says “[f]or me, more than anything, it’s a family reunited. An entire century passed, and we’re together again.”

In an animated scene that brings to mind the catch between John and Roy Kinsella, father and son, in Field of Dreams, Tokyo Giant: The Legend of Victor Starffin concludes with a loving game of catch between Victor, Elizabeth, and Natasha, who says “my father has always been in my heart. I’ve felt that he always watches over me from heaven.” This heartwarming moment reminds the audience of the importance of family and is a testament to the enduring love that the Starffin family has for each other. Released in 2022 and directed by Tchavdar Georgiev, this film can be streamed on Amazon Prime Video and Roku. Tokyo Giant: The Legend of Victor Starffin is a film not only about baseball and history, but, most notably, also, one about the Starffin family’s grace, persevering courage, and motivating journey of reconnection. I highly recommend this film.