by Ralph Pearce

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Ralph Pearce discusses the Japanese American San Jose Asahi’s 1925 tour of Japan and Korea.

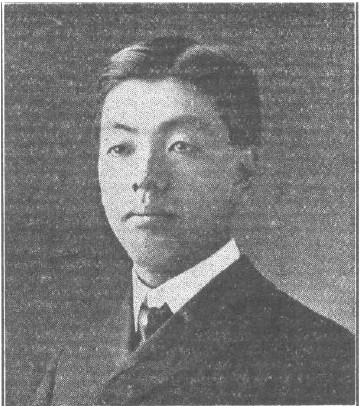

The San Jose Asahi Baseball Club was one of a number of Japanese teams to organize in Northern California between 1903 and 1915. Other cities to organize early teams included San Francisco, Oakland, Alameda, and Florin. The name Asahi means Morning Sun in Japanese and was a popular team name. San Jose’s first Asahi team was made up of Issei (first-generation immigrants) players and lasted only a few years. In 1918 one of the former Issei players encouraged a young Nisei (second-generation) fellow, Jiggs Yamada, to reconstitute the team with Nisei players. Jiggs, a catcher, enlisted the assistance of 15-year-old pitcher Russell Hinaga, and the two soon put a team together.

Unlike the Issei players, these young Nisei players were bom in the United States and had attended English-language schools with a largely Caucasian enrollment. Because of this, both a generational and cultural gap existed between the Issei and Nisei. Through the shared love of baseball, Nisei teams like the San Jose Asahi helped bridge this divide. In the early 1920s, a sympathetic newspaper columnist in San Jose, Jack Graham, encouraged the Asahi to extend that bridge by participating in games outside the Japanese leagues. This participation drew the larger San Jose community to the Asahi Diamond in Japantown, and there Caucasians began to mingle with Japanese Americans, helping to establish familiarity and friendship.

Another bridge in the making was the growing baseball friendship between the United States and Japan. Japan’s enthusiasm for the game had been spreading since its introduction in the 1870s. The tradition of international baseball exchanges began with Waseda University’s 1905 tour of the American West Coast and continues to this day. This friendship through the two nations’ shared love of baseball helped foster cultural appreciation and understanding.

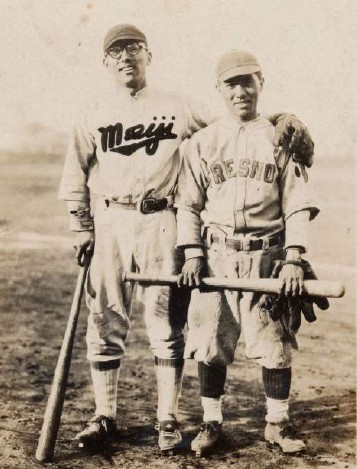

San Jose’s opportunity to visit Japan came in 1925 at the invitation of Meiji University, whose baseball club had toured the United States the year before. The timing couldn’t have been better for the Asahi; several of the players—Jiggs Yamada, Morio “Duke” Sera, Fred Koba, and Earl Tanbara—were anticipating retirement from the team. It was agreed that they would stay with the Asahi until their return from Japan.

It is believed that Meiji University provided some funds for tour expenses, though much of the burden was on the team and its Issei supporters. The first obstacle was the cost of transporting 17 passengers to and from Japan. Jiggs Yamada explained how this was accomplished:

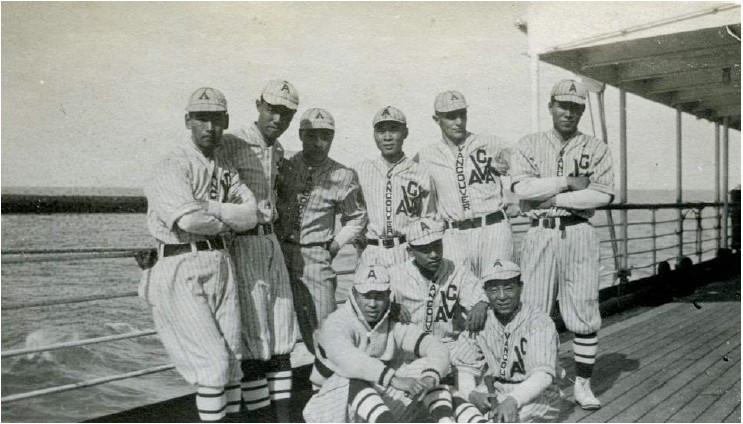

Well first, we had to get some way to go to Japan. A boat was the only thing we could get. We happened to have a boy, Earl Tanbara. … Tanbara’s folks, mother and father, worked for the Dollar Steamship Company family in Piedmont. So when he graduated high school, we had his father talk to Mr. Dollar and ask him if he could do us a favor. He said, “Sure, as soon as Earl [goes] to Cal [Berkeley] and graduated, he’s got to work for me at the steamship company.” They were going to open up an agent in India. So he said, “Sure, if he promises to do that, I can have him going on our boat to Japan.” .. .So that’s how we got to go to Japan on a boat. People figured it was funny how we got to go to Japan . because at that time the steamship boat was expensive.

A few days before departure, Asahi supporter Seijiro Horio gave $800 to Nobukichi Ishikawa, the team’s treasurer. This appears to have been the primary funding source for the team’s trip.

Jack Graham publicized the coming tour to Japan in a number of articles. On March 18, 1925, the day before the team departed, he wrote: “There will be a big delegation of fans in attendance and a bumper crowd of Japanese fans will be on hand to see their favorite sons in their final game in this city. The Asahi team will sail on Saturday for Japan, where they will play a series of games in the flowery kingdom. On their return, they will stop in the Hawaiian Islands, where they will play seven or more games. It will be the latter part of June before they return. The Asahi team has made many friends in this city by their gentlemanly manner in playing the national game, and whenever they stage a game here there is always sure to be a big turn-out.”

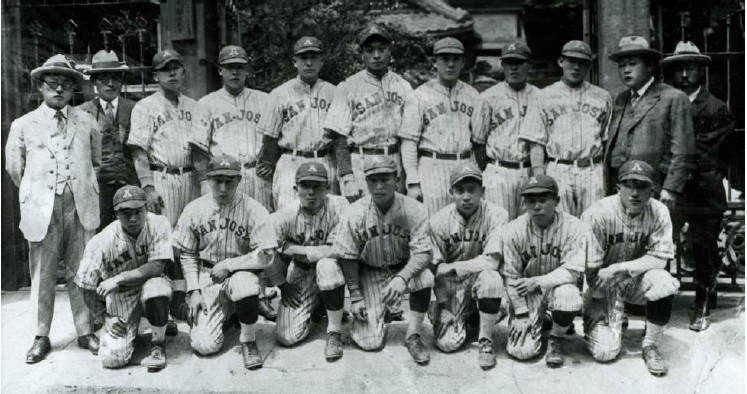

The next day, Graham ran a column praising the Asahi and encouraging local pride in the team as representatives of San Jose. A large photograph of the team ran at the top of the sports section, remarkable in that images of local teams rarely appeared in either American or Japanese American papers at the time. The caption read in part: “The Japanese Asahi baseball team will leave San Jose on the first leg of its joumey to the land of cherry blossoms this morning, when it takes the train to San Francisco where it will stay until Saturday, when it will embark on the President Cleveland for Japan.”

The team members making the trip to Japan were pitchers Jimmy Araki and Russell Hinaga; catchers Ed Higashi and Jiggs Yamada; first baseman Harry Hashimoto; second baseman Tom Sakamoto; third baseman Morio “Duke” Sera; shortstop Fred Koba; third baseman-outfielder Sai “Cy” Towata; outfielders Frank Takeshita, Frank Ito, and Earl Tanbara; and utility players Jitney Nishida and Jimmie Yoshida. While the team was in Japan, the strong Asahi “B” team continued to play in San Jose against teams of its caliber. Asahi Diamond was also made available for use by other local teams and management of the diamond was temporarily turned over to locals Happy Luke Williams and Chet Maher.

The Asahi, along with the trip’s manager, Kichitaro Okagaki, and its treasurer, Nobukichi Ishikawa, left San Francisco on March 21, 1925, and a little over two weeks later they arrived in Japan, giving them about a week to recover before their first game. When the team arrived in Japan, Earl Tanbara purchased two Mizuno baseball scorebooks. Earl kept meticulous track of each game, including dates, locations, and the names of all the players.

The Asahi played their first game on Thursday, April 9, against their hosts Meiji University. They lost 8-2 with Araki going the distance on the Meiji grounds. The Asahi played their second game on Saturday, April 11, against Waseda University. They were playing better now, though they lost in a 12-9 slugfest. Russ Hinaga and Jimmy Araki shared the pitching chores, Frank Ito got a double, Harry Hashimoto had a triple, and Cy Towata and Earl Tanbara hit home runs. Each side recorded only one error.

The Asahi played their third game two days later with a rematch against their hosts, Meiji University. Jimmy Araki again pitched the entire game with Ed Higashi doing the catching. Araki was knocked around for a 9-4 loss, despite a batch of errors by Meiji. Next up—the very next day—was Keio University, another tough team. If the Asahi were ready for a win, it would have to wait for another day. Araki and Hinaga pitched the team to a 20-4 shellacking, the Asahi racking up seven errors along the way.

Two days later, on April 16, the Asahi faced Tokyo Imperial University. Once again Araki and Hinaga teamed up. The team was sharper that day, making only one error. Harry Hashimoto hit two doubles, chalking up a run. That was the Asahi’s only run, though, to six for Tokyo and their fifth loss in five games. The Asahi played for the love of the game, but they were serious competitors and this situation was not acceptable. Jiggs Yamada explained the problem and the remedy:

We didn’t play so good because our legs were shaking and all that and the ball was different. It was a regular size American ball, but the cowhide, it slips. The pitcher couldn’t play, pitch curves or anything and the players themselves couldn’t throw the bases, so we couldn’t play good. So finally we told the manager [Okagaki] of our team “Get us some American balls.” So they sent us a one dozen box of American balls, then we started to play different. Then we started to play our regular play.

Teammate Duke Sera confirmed the situation, saying that after leaving Tokyo, the manager saw to it that future Japanese teams could use their own baseballs when they were in the field, and that the Asahi players would use American balls when they were in the field.

On April 18, the Asahi played yet another strong university nine. This time it was against Hosei. Jimmy Araki took to the mound for the Asahi and despite several errors, the team finally got its first win. The Asahi won 7-4 and scored all their runs in the first three innings, thanks in part to a home run by Araki himself. The team followed up a week later with a 25-5 victory over Sendai, with Hinaga pitching and Araki sharing left field with Tanbara. The Asahi suffered another loss on May 1, against Takarazuka before beginning a 13-game winning streak.

The Asahi had played their first six games in Tokyo against strong university teams before venturing north to Sendai. From Sendai, they headed south about 500 miles to Osaka. They played three games in the Osaka area and one game in nearby Kyoto. In the game against Kyoto Imperial University, Tom Sakamoto hit a dramatic “Sayonara Home Run” or walk-off home run in the 10th inning to win 3-2.

From Osaka, the team headed south to Hiroshima for two games. As they traveled the country by train, they continued to accumulate wins and, more importantly, became acquainted with the land of their parents.

One of the players, Duke Sera, had been bom in Hawaii, and then raised by his uncle in Hiroshima. His uncle had sent him to Stanford University to complete his education. When the team visited Hiroshima, Duke’s uncle held a reception for the team. According to Yamada, when the uncle met Duke and the team he quipped, “What the hell are you doing with this bunch here? You’re supposed to be studying!”

After the final game in Hiroshima on May 12, the Asahi traveled 400 miles back to Tokyo. It was the team’s original intention to return to the United States sometime in June. Whatever plans they may have had, however, were altered upon their return to Tokyo (except for Duke Sera, who had to return to his studies at Stanford). Jiggs shared the change of plans:

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website