SABR member Ray Nickson work on early Japanese baseball in Australia is featured on the website The Conversation.

Category: Nikkei

-

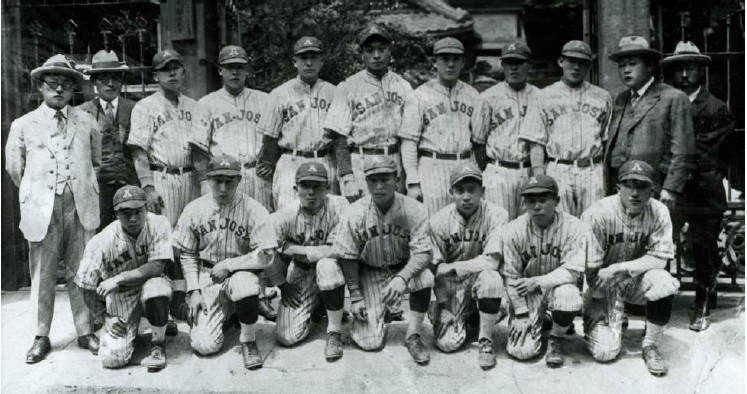

San Jose Asahi’s 1925 Tour of Japan and Korea

by Ralph Pearce

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Ralph Pearce discusses the Japanese American San Jose Asahi’s 1925 tour of Japan and Korea.

The San Jose Asahi Baseball Club was one of a number of Japanese teams to organize in Northern California between 1903 and 1915. Other cities to organize early teams included San Francisco, Oakland, Alameda, and Florin. The name Asahi means Morning Sun in Japanese and was a popular team name. San Jose’s first Asahi team was made up of Issei (first-generation immigrants) players and lasted only a few years. In 1918 one of the former Issei players encouraged a young Nisei (second-generation) fellow, Jiggs Yamada, to reconstitute the team with Nisei players. Jiggs, a catcher, enlisted the assistance of 15-year-old pitcher Russell Hinaga, and the two soon put a team together.

Unlike the Issei players, these young Nisei players were bom in the United States and had attended English-language schools with a largely Caucasian enrollment. Because of this, both a generational and cultural gap existed between the Issei and Nisei. Through the shared love of baseball, Nisei teams like the San Jose Asahi helped bridge this divide. In the early 1920s, a sympathetic newspaper columnist in San Jose, Jack Graham, encouraged the Asahi to extend that bridge by participating in games outside the Japanese leagues. This participation drew the larger San Jose community to the Asahi Diamond in Japantown, and there Caucasians began to mingle with Japanese Americans, helping to establish familiarity and friendship.

Another bridge in the making was the growing baseball friendship between the United States and Japan. Japan’s enthusiasm for the game had been spreading since its introduction in the 1870s. The tradition of international baseball exchanges began with Waseda University’s 1905 tour of the American West Coast and continues to this day. This friendship through the two nations’ shared love of baseball helped foster cultural appreciation and understanding.

San Jose’s opportunity to visit Japan came in 1925 at the invitation of Meiji University, whose baseball club had toured the United States the year before. The timing couldn’t have been better for the Asahi; several of the players—Jiggs Yamada, Morio “Duke” Sera, Fred Koba, and Earl Tanbara—were anticipating retirement from the team. It was agreed that they would stay with the Asahi until their return from Japan.

It is believed that Meiji University provided some funds for tour expenses, though much of the burden was on the team and its Issei supporters. The first obstacle was the cost of transporting 17 passengers to and from Japan. Jiggs Yamada explained how this was accomplished:

Well first, we had to get some way to go to Japan. A boat was the only thing we could get. We happened to have a boy, Earl Tanbara. … Tanbara’s folks, mother and father, worked for the Dollar Steamship Company family in Piedmont. So when he graduated high school, we had his father talk to Mr. Dollar and ask him if he could do us a favor. He said, “Sure, as soon as Earl [goes] to Cal [Berkeley] and graduated, he’s got to work for me at the steamship company.” They were going to open up an agent in India. So he said, “Sure, if he promises to do that, I can have him going on our boat to Japan.” .. .So that’s how we got to go to Japan on a boat. People figured it was funny how we got to go to Japan . because at that time the steamship boat was expensive.

A few days before departure, Asahi supporter Seijiro Horio gave $800 to Nobukichi Ishikawa, the team’s treasurer. This appears to have been the primary funding source for the team’s trip.

Jack Graham publicized the coming tour to Japan in a number of articles. On March 18, 1925, the day before the team departed, he wrote: “There will be a big delegation of fans in attendance and a bumper crowd of Japanese fans will be on hand to see their favorite sons in their final game in this city. The Asahi team will sail on Saturday for Japan, where they will play a series of games in the flowery kingdom. On their return, they will stop in the Hawaiian Islands, where they will play seven or more games. It will be the latter part of June before they return. The Asahi team has made many friends in this city by their gentlemanly manner in playing the national game, and whenever they stage a game here there is always sure to be a big turn-out.”

The next day, Graham ran a column praising the Asahi and encouraging local pride in the team as representatives of San Jose. A large photograph of the team ran at the top of the sports section, remarkable in that images of local teams rarely appeared in either American or Japanese American papers at the time. The caption read in part: “The Japanese Asahi baseball team will leave San Jose on the first leg of its joumey to the land of cherry blossoms this morning, when it takes the train to San Francisco where it will stay until Saturday, when it will embark on the President Cleveland for Japan.”

The team members making the trip to Japan were pitchers Jimmy Araki and Russell Hinaga; catchers Ed Higashi and Jiggs Yamada; first baseman Harry Hashimoto; second baseman Tom Sakamoto; third baseman Morio “Duke” Sera; shortstop Fred Koba; third baseman-outfielder Sai “Cy” Towata; outfielders Frank Takeshita, Frank Ito, and Earl Tanbara; and utility players Jitney Nishida and Jimmie Yoshida. While the team was in Japan, the strong Asahi “B” team continued to play in San Jose against teams of its caliber. Asahi Diamond was also made available for use by other local teams and management of the diamond was temporarily turned over to locals Happy Luke Williams and Chet Maher.

The Asahi, along with the trip’s manager, Kichitaro Okagaki, and its treasurer, Nobukichi Ishikawa, left San Francisco on March 21, 1925, and a little over two weeks later they arrived in Japan, giving them about a week to recover before their first game. When the team arrived in Japan, Earl Tanbara purchased two Mizuno baseball scorebooks. Earl kept meticulous track of each game, including dates, locations, and the names of all the players.

The Asahi played their first game on Thursday, April 9, against their hosts Meiji University. They lost 8-2 with Araki going the distance on the Meiji grounds. The Asahi played their second game on Saturday, April 11, against Waseda University. They were playing better now, though they lost in a 12-9 slugfest. Russ Hinaga and Jimmy Araki shared the pitching chores, Frank Ito got a double, Harry Hashimoto had a triple, and Cy Towata and Earl Tanbara hit home runs. Each side recorded only one error.

The Asahi played their third game two days later with a rematch against their hosts, Meiji University. Jimmy Araki again pitched the entire game with Ed Higashi doing the catching. Araki was knocked around for a 9-4 loss, despite a batch of errors by Meiji. Next up—the very next day—was Keio University, another tough team. If the Asahi were ready for a win, it would have to wait for another day. Araki and Hinaga pitched the team to a 20-4 shellacking, the Asahi racking up seven errors along the way.

Two days later, on April 16, the Asahi faced Tokyo Imperial University. Once again Araki and Hinaga teamed up. The team was sharper that day, making only one error. Harry Hashimoto hit two doubles, chalking up a run. That was the Asahi’s only run, though, to six for Tokyo and their fifth loss in five games. The Asahi played for the love of the game, but they were serious competitors and this situation was not acceptable. Jiggs Yamada explained the problem and the remedy:

We didn’t play so good because our legs were shaking and all that and the ball was different. It was a regular size American ball, but the cowhide, it slips. The pitcher couldn’t play, pitch curves or anything and the players themselves couldn’t throw the bases, so we couldn’t play good. So finally we told the manager [Okagaki] of our team “Get us some American balls.” So they sent us a one dozen box of American balls, then we started to play different. Then we started to play our regular play.

Teammate Duke Sera confirmed the situation, saying that after leaving Tokyo, the manager saw to it that future Japanese teams could use their own baseballs when they were in the field, and that the Asahi players would use American balls when they were in the field.

On April 18, the Asahi played yet another strong university nine. This time it was against Hosei. Jimmy Araki took to the mound for the Asahi and despite several errors, the team finally got its first win. The Asahi won 7-4 and scored all their runs in the first three innings, thanks in part to a home run by Araki himself. The team followed up a week later with a 25-5 victory over Sendai, with Hinaga pitching and Araki sharing left field with Tanbara. The Asahi suffered another loss on May 1, against Takarazuka before beginning a 13-game winning streak.

The Asahi had played their first six games in Tokyo against strong university teams before venturing north to Sendai. From Sendai, they headed south about 500 miles to Osaka. They played three games in the Osaka area and one game in nearby Kyoto. In the game against Kyoto Imperial University, Tom Sakamoto hit a dramatic “Sayonara Home Run” or walk-off home run in the 10th inning to win 3-2.

From Osaka, the team headed south to Hiroshima for two games. As they traveled the country by train, they continued to accumulate wins and, more importantly, became acquainted with the land of their parents.

One of the players, Duke Sera, had been bom in Hawaii, and then raised by his uncle in Hiroshima. His uncle had sent him to Stanford University to complete his education. When the team visited Hiroshima, Duke’s uncle held a reception for the team. According to Yamada, when the uncle met Duke and the team he quipped, “What the hell are you doing with this bunch here? You’re supposed to be studying!”

After the final game in Hiroshima on May 12, the Asahi traveled 400 miles back to Tokyo. It was the team’s original intention to return to the United States sometime in June. Whatever plans they may have had, however, were altered upon their return to Tokyo (except for Duke Sera, who had to return to his studies at Stanford). Jiggs shared the change of plans:

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

-

Kenichi Zenimura, ‘The Father of Japanese American Baseball,’ and the 1924, 1927, and 1937 Goodwill Tours

by Bill Staples, Jr.

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Bill Staples, Jr. tell us about one of the most important Japanese American baseball players–Kenichi Zenimura and three of the tours he organized.

Few baseball fans know the story of early twentieth-century Nikkei (Japanese American) baseball. Despite this lack of awareness, the Nikkei impact is still visible in today’s game. It’s subtle, though, visible only to the well-informed. The legacy is not a retired uniform number displayed inside a major-league ballpark, but the names on the back of the uniforms. In 2022 those names are Akiyama, Darvish, Kikuchi, Maeda, Ohtani, Sawamura, and Suzuki—and in 2025, it will almost certainly include Ichiro on a plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The national pastime has unofficially become the international pastime, and this is the enduring legacy of Nikkei baseball and the work of pioneers like Kenichi Zenimura (1900-1968).

During the years 1923 to 1930, no major-league team barnstormed in Japan. The highest-caliber competition from the United States during this time came in the form of Nikkei and Negro League teams like Zenimura’s Fresno Athletic Club (FAC) and the Philadelphia Royal Giants. During this major-league void, Nikkei and Negro Leaguers helped elevate the level of play in Japan and set the stage for the 1931 and 1934 tour of stars like Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, and the start of the professional Japanese Baseball League in 1936.

In 1962 Zenimura was crowned the “Dean of Nisei Baseball” by veteran Fresno Bee sports reporter Tom Meehan. Shortly after Zeni’s death in 1968, the same sentiment was echoed by Bee reporter Ed Orman. Approximately 25 years later, baseball historian Kerry Yo Nakagawa refined that tribute for a new audience, calling Zenimura “The Father of Japanese American Baseball.” Nakagawa and others believe that Zeni deserves this title for his unparalleled career and collective impact as a player, manager, and global ambassador.

PREWAR GOODWILL AMBASSADOR

Between 1905 and 1940, roughly one out of four (26.5 percent) tours across the Pacific featured a Nikkei team visiting Japan. When examining the tours between 1923 and 1940, Zenimura’s impressive impact becomes apparent. Of the 53 tours during this period, Zenimura was involved, to some degree, with 17 (32 percent) of those efforts. When he himself was not traveling, Zeni supported or influenced 14 different tours by other Nikkei teams, visiting Japanese ballclubs, Negro League teams, and major-league all-stars.

The following is an in-depth look at Zenimura’s three major tours—1924, 1927, and 1937—in which he participated directly, allowing him to shine in his homeland of Japan.

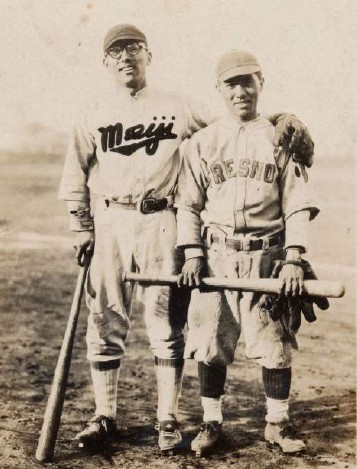

Kenichi Zenimura (right) with his cousin Tasumi Zenimura (left) in 1928. THE 1924 TOUR

The seeds for Zenimura’s 1924 tour were planted on Independence Day in 1923 when the Fresno Athletic Club battled the Seattle Asahi for the National Nikkei Baseball Championship. The Asahi had earned the respect of the baseball world by winning the majority of their games during tours to Japan between 1915 and 1923. In a best-of-three series, the FAC defeated the Asahi to become the undisputed Nikkei baseball champions. With the victory, Fresno also won the right to tour Japan the following year.

In preparation for the tour, the FAC scheduled games against high-caliber competition, including the Pacific Coast League Salt Lake City Bees, who conducted spring training in Fresno. In a three-game series, the FAC surprised the Bees with a 6-4 victory in game one, marking the first time a Nikkei team defeated a PCL ballclub. The series also marked the presence of Frank “Lefty” O’Doul. Newly signed from San Francisco, O’Doul did not compete in the loss, but his powerful bat helped the Bees take games 2 and 3.

More important than O’Doul’s on-field performance was the historical significance of his involvement. The gregarious southpaw would later be enshrined in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame for his life’s work as a celebrated ambassador of US-Japan baseball relations. Most likely, this 1924 encounter marks O’Doul’s first interaction with ballplayers of Japanese ancestry.

On September 2, 1924, the FAC boarded the SS President Pierce for Japan.Six weeks later they stepped inside Koshien Stadium to play their first opponent, Daimai. The FAC recorded a shutout 5-0 victory behind the arm of Kenso “The Boy Wonder” Nushida. Fresno pitchers did not allow a run until their third game, on October 14, a 4-3 loss in a rematch with Daimai.

During their 46-day stay in Japan (October 11 to November 26), the Fresno team traveled approximately 1,300 miles (about 2,100 kilometers), covering nine cities—starting in Osaka, with stops in smaller locales between Hiroshima, Tokyo, and Yokohama. They played 27 games, finishing with a 20-7 record and an overall .741 winning percentage.

After watching the Fresno captain compete on the field, a reporter with the Japan Times wrote, “Zenimura is one of the smartest and most colorful players the writer had ever seen. He was the terror of the diamond, a man who played every position in baseball. He was tricky, shrewd and positive poison to every opponent.”

In Tokyo, Zeni penned his thoughts on the Japan tour experience in a letter to the Fresno Morning Republican, which was published on December 5. It read:

Tokyo, Japan

November 16, 1924Mr. T.P. Spink

Sports Editor,

The Republican.Dear Sir: –

The Fresno team is doing a [sic] good work in Japan and so far our record stands 18 victories and 5 lost. In today’s game we played against Keio and defeated them by the score of 8-to-4. We gave the last four runs in the last of the ninth after two men gone.

In Japan it doesn’t pay to win a game in a far margin. If we do then there won’t be any crowd coming to the next game, saying that we are too strong for this Japan team and so on. We had many examples in Osaka.

Beat Diamonds

One day we played against the pro team of Osaka which is known as Diamonds and in our first game we defeated them by a score of ll-2. In this game quite a many fans [sic] came to see the outcome but on the following day with the same teams there was hardly any people in the stand[s]. For this reason, it is hard for the visiting team to play a game in Japan.

Another thing disadvantaging us is the way these Tokyo umpires calls [sic] on decisions against us. … I can’t figure the way these umpires make a bad decision when ever the play is close. We had enough of the raw decisions in Tokyo, but what can we do in Japan!!!

Meet Champions

Tomorrow we are playing against Waseda, the intercollegiate champions of Japan. We hope to beat them badly and by the time this letter reaches you, you will be able to get the result.

On the way to the States I am figuring of stopping over to Honolulu and spend my Christmas and New Year’s there. About five of the players are going to do the same and eleven of the remaining players will be in Fresno by 13th of December 1924.

As soon as the team reaches to Fresno we would like to play a three game series with the Fresno Tigers.

Yours truly,

K. ZENIMURA

(Captain).The Waseda contest mentioned in the letter resulted in a 3-2 loss for Fresno. FAC lost the game, but won the respect of the opposing manager, Chujun Tobita. He praised the visiting team’s baseball skills, saying they were “amazing” in their demonstration of technique and power.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

-

1921 Vancouver Asahi’s Tour to Japan

by Satoshi Matsumiya and Yobun Shima

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Satoshi Matsumiya and Yobun Shima focus on the 1921 tour of Japan by the Vancouver Asahi.

The Vancouver Asahi team was formed in 1914 with players who were mostly graduates of the Vancouver Japanese Community National School. Ihachi Miyasaki (a.k.a. Matsujiro Miyasaki), who ran a transportation business, became the manager of the team, which was organized through the Shiga Prefecture network and Matsumiya stores’ connections. The team played and practiced in vacant lots near the school and at Powell Grounds.

In 1918, the Asahi was reorganized under the leadership of president Sotojiro Matsumiya by recruiting top players from nearby Japanese Canadian teams (such as the Yamato, Mikado, and Victoria Nippon) to form a stronger team now named the Asahi Baseball Club. In July 1918 they formed the Vancouver International League with Caucasian teams and started to play league games. That year, the Asahi finished second in the International League but lost the playoffs. The following year, they won the International League with an overwhelming record of 11 wins and 1 loss. Although the Asahi featured a full lineup of Japanese players against White teams who were bigger and more powerful, they showed that teamwork and smart game play could win the league championship. Japanese Canadian baseball fans were excited by the victory and gathered at the Powell Street Grounds to share their hopes for an Asahi tour to Japan. But team members said, “No, it’s too early for that. We will have to polish our team’s skills before demonstrating them to the Japanese people in our ancestral country.”

In 1920 the presidency of the Asahi team changed to Henry Masataro Nomura, who decided to rename the team the Asahi Athletic Club, withdraw from the International League, and join the higher-ranked Vancouver City League to improve Asahi’s performance. Nomura had relocated in 1917 from St. Louis to Vancouver, where he started practicing dentistry on the second floor of Royal Bank. He was a passionate advocate of a theory for healthy baseball and sports but some of the players did not agree with him and they sometimes rebelled.

Asahi finished third in the City League in the 1920 season with a record of 10 wins and 14 losses. At the end of the season, there was a resurgence of talk about a tour to Japan. Some Japanese Canadians enthusiastically proposed that the team should demonstrate their baseball ability in their ancestral country to help raise the spirits of the team’s players. It was around this time that Yuji Uchiyama, one of the Asahi players, had returned to Vancouver after accompanying the Seattle Mikado team on their Japan tour. Uchiyama told the Asahi players about the current baseball situation in Japan. The Japanese Canadian Nisei (second-generation) players, who hoped of visiting their motherland, listened to him with shining eyes, and the team’s expectations for a tour to Japan rose at once. Nomura, as the leader of the team, showed great interest in the idea of a Japan tour and told many people about the plan to help gain support. Nevertheless, six players (Barry Kiyoshi Kasahara, Harry Miyasaki, Junji George Ito, Bull Oda, Tom Nichi Matoba and Sotaro Matsumiya) decided to withdraw from the Asahi team to form a new baseball club named the Vancouver Asahi Baseball Team (also known as the Tigers). The two groups were not in agreement over whether to go on the Japan tour. It was also rumored that they were divided over Nomura’s management policy.

Nomura’s Asahi Athletic Club rejoined the City League while the new Vancouver Asahi Baseball Team (the Tigers) joined the Terminal League, which had been previously known as the International League. Therefore, the two Asahi teams played in separate leagues. At the end of the 1921 season, the Asahi Athletic Club decided to follow Nomura’s plan and go on a tour to Japan.

On August 24, the day of the departure for Japan, a send-off party for the team was held at the Yang Ming Lou restaurant. Tour leader Nomura said, “We have been negotiating with Makoto [Shin] Hashido of the Japan Athletic Association for a long time. And they decided to invite us to Japan officially, so here we are today. The games will be played mainly against the Japanese university teams. And we will also visit Hokkaido plus Kansai to foster friendship between Japan and Canada.”

The touring party consisted of 19 members: 12 Japanese players, four Caucasian players, and three leaders. These were Henry Masataro Nomura and his wife, Lovenda; scorer Yosomatsu (Nishizaki) Horii; umpire Dr. Fletcher; pitchers Mickey Kitagawa (captain), Tokikazu Tanaka, and Tat Larson; catchers Yo Horii, and Jack Wyard; first baseman Happy Yoshioka; second basemen Joe Nimi and Yuji Uchiyama (manager); third baseman Ernie Paepke (coach); shortstop George Iga; left fielders Joe Brown and Tamotsu Miyata; center fielder Eddie Kitagawa; right fielder Ted Furumoto; and substitute Takashi Kikukawa. The four Caucasian players were added to the Japan tour team for promotional reasons and to reinforce the squad.

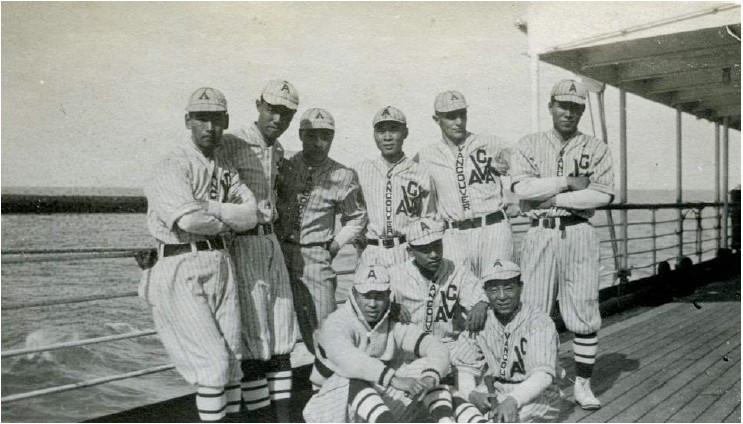

The players’ spirits were high because the Japan trip was not only a tour of their ancestral country but was also a mission to promote friendship between Canada and Japan and to introduce British Columbian industry. The players received new uniforms, enjoyed the send-off party, and each expressed his determination to do his best. At 11:30 P.M., about 200 Japanese Canadians and Caucasians gathered at the pier to see the team off. The players lined up on the deck of the Kashima Maru with bouquets of flowers in their hands, donated by volunteers, and shouted “Banzai! Banzai!” The ship sailed off with a whoosh that pierced the air. A series of reports about the tour were to be written by manager Yuji Uchiyama and sent to the Tairiku Nippo (Continental Daily Newspaper) in Vancouver under the title “The Baseball Tour.”

The trip to Japan took two weeks. Also traveling on the Kashima Maru was the University of Washington baseball team, which was also touring Japan. In all, 10 teams from North America and Hawaii toured Japan that year: the University of California, Washington University, the Hawaiian Nippon, the Hawaiian Hilo, the Hawaii All-Stars, the Canadian Stars, the Suquamish Indians, the Sherman Indians, the Seattle Asahi, and the Vancouver Asahi. All of them were hoping to play with Japanese university teams. This phenomenon showed how popular Japanese baseball had become and how active baseball exchanges between Japan and the United States were.

As the voyage progressed, the Asahis played catch, ran, and played pepper on the deck during the day to prevent their bodies from getting too slow. Sometimes, their precious baseballs flew overboard into the sea. In the evening they met to discuss strategy and learn the signs. There were some players, however, who could not get up from their beds owing to seasickness.

On September 9 in the evening, after the long voyage, the Kashima Maru at last dropped anchor at Yokohama Port.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

-

Baseball returns to a Japanese American detention camp after a historic ball field was restored.

article from The Conversation

In the spring of 1942, 15-year-old Momo Nagano needed a way to fill her time.

She was imprisoned at the Manzanar Relocation Center along with approximately 10,000 other people of Japanese ancestry. When she’d arrived with her mother and two brothers, she’d been horrified.

The detention facility was located in the middle of the desert, about 225 miles northeast of Los Angeles. As I describe in my book “When Can We Go Back to America? Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II,” barbed wire surrounded the perimeter and armed soldiers peered down from guard towers. The toilets and showers lacked partitions, and Nagano was forced to stand in long lines for hours in mess halls that served canned food. Her bed was a metal cot. She was directed to stuff straw into a bag for a makeshift mattress. She didn’t know whether she and her family would ever be able to return to their Los Angeles home.

One day, the teenager decided to pick up a glove and play softball. Her son, Dan Kwong, told me in an interview that Nagano ended up playing catcher for The Gremlins, one of the camp’s many women’s softball teams.

“In one game, a batter connected with the ball and then threw the bat, clocking my mom in the nose, breaking it,” he said. “But despite her injury, she still enjoyed playing, even though she didn’t think her team was very good.”

Eighty years later, the descendants of prisoners – such as Nagano’s son, Kwong – are playing baseball again in Manzanar. Thanks to an effort spearheaded by Kwong, a baseball field on the site has been restored as a way to both celebrate the resiliency of so many prisoners and memorialize this dark period in U.S. history.

READ the rest of the article at The Conversation

-

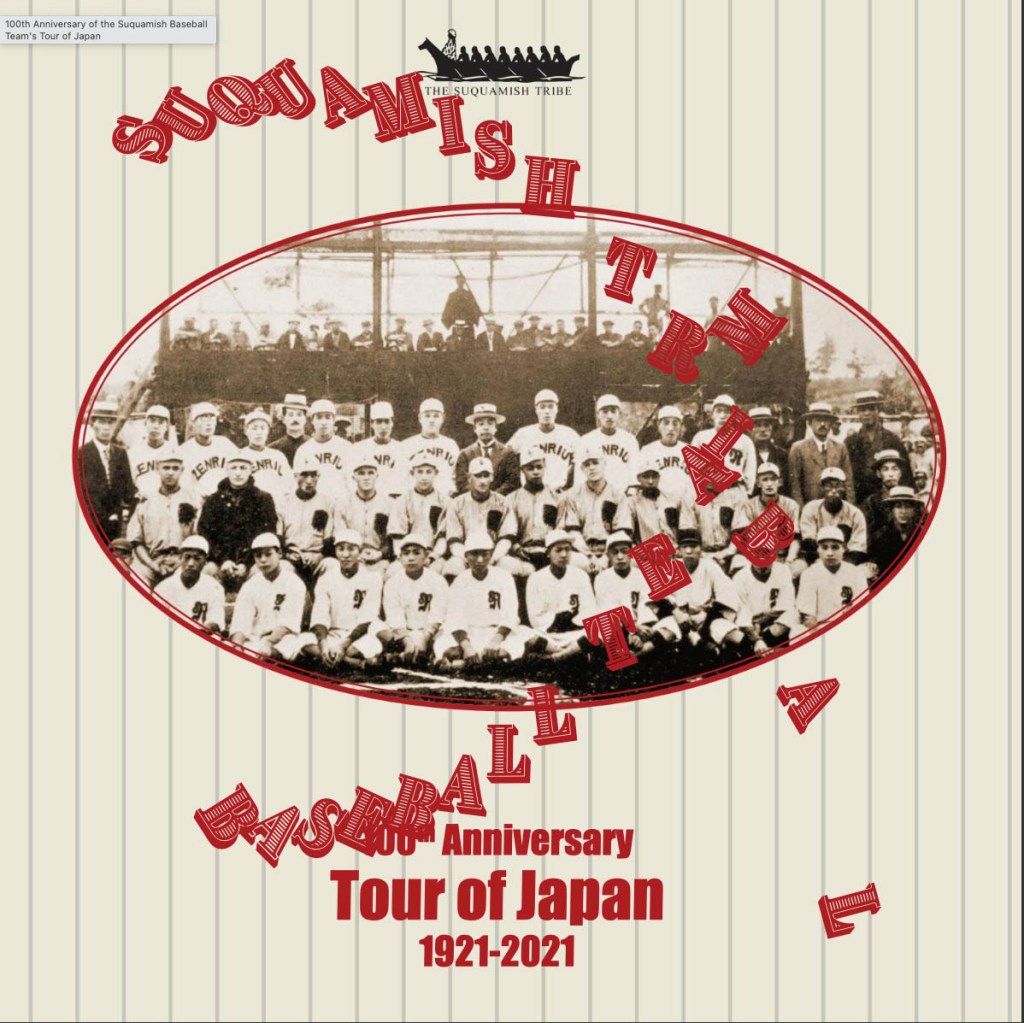

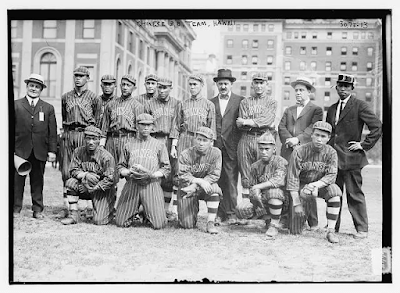

The 1921 Native American Tours of Japan

by Yoichi Nagata, Mark Brunke and Rob Fitts

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. Today Yoichi Nagata, Mark Brunke and Rob Fitts focus on the two Native American baseball tours of Japan which both took place in 1921. This article was selected as a winner of the 2023 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

In the late nineteenth century as the American frontier closed, the myth of the Wild West began. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, dime novels, and, later, Western movies created a fictitious past dominated by stereotypes of cowboys, gunslingers, and Indians. In most of these genres, Native Americans were depicted as exotic, almost non-human, wild and cruel savages. This stereotype proliferated throughout the United States, Europe, and even Japan. Nonetheless, Wild West entertainment became popular throughout the United States and Europe. In 1921 two baseball promoters tried separately to capitalize on this international fad by bringing Native American baseball teams to Japan. But neither tour turned out as planned.

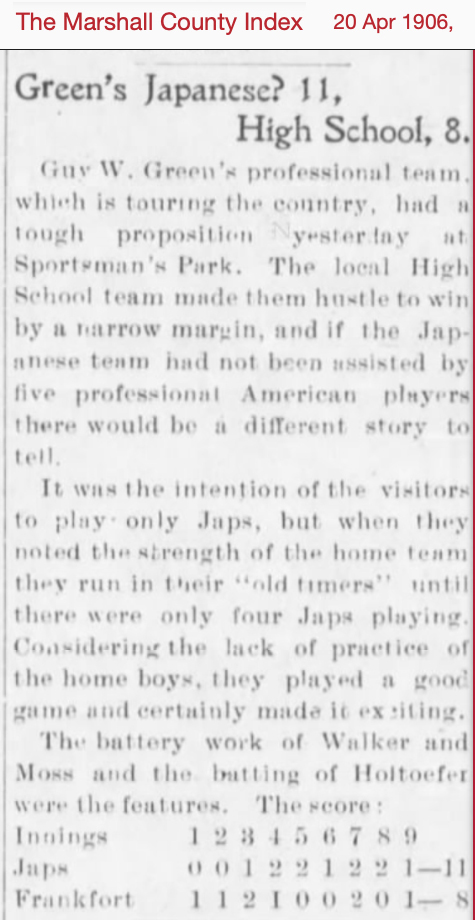

The genesis for these tours took place on the Nebraska plains in 1895 when Guy Wilder Green, a law student at the University of Nebraska and player-manager of the Stromsburg town baseball club, organized a game against the Genoa Indian Industrial School. To his surprise, “Even in Nebraska, where an Indian is not at all a novelty … when the Indians came to Stromsburg, business houses were closed and men, women and children turned out en masse. … I reasoned that if an Indian base ball team was a good drawing card in Nebraska, it ought to do wonders further east if properly managed.” After graduating from law school in 1897, Green created the All-Nebraska Indian Base Ball Team (soon shortened to the Nebraska Indians) which became one of the nation’s most popular barnstorming baseball clubs. From 1897 to 1906 the Nebraska Indians played 1,637 games in 17 states and Canada.

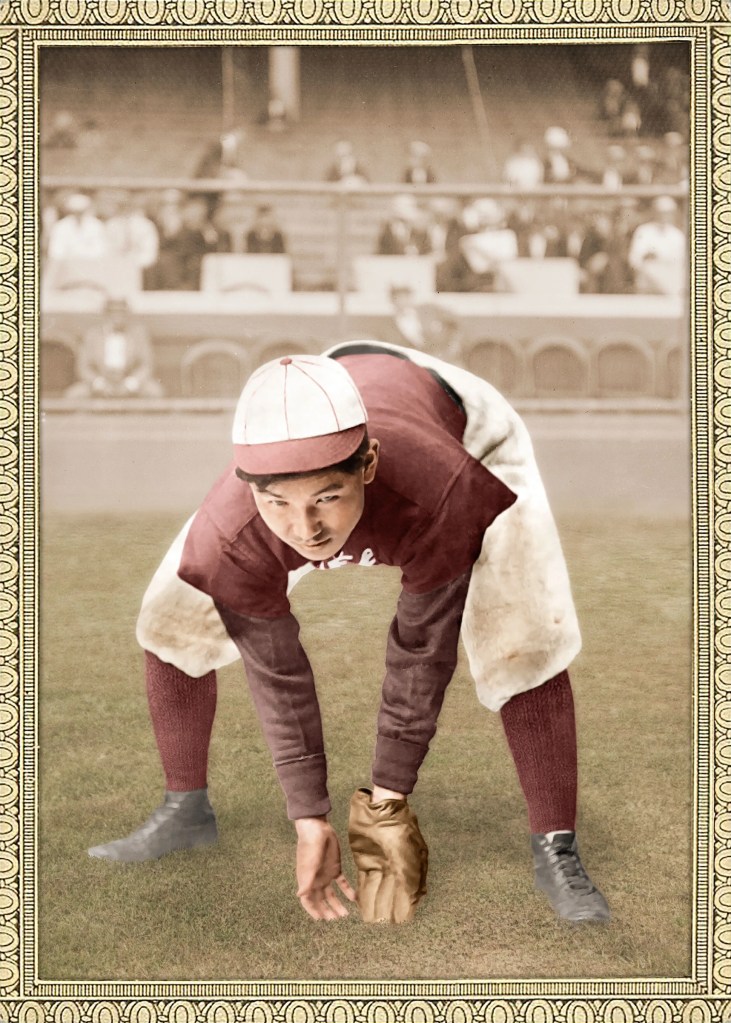

In 1906 much of the United States was enthralled by all things Japanese. Japan had just emerged as the improbable victor in the Russo-Japanese War, and the Waseda University baseball club had recently toured the West Coast. Green decided to capitalize on the fad by creating an all-Japanese baseball club to barnstorm across the Midwest. It became the first Japanese professional team on either side of the Pacific, as pro ball would not come to Japan until 1921.

1906 Advertising Card, Ken Kitsuse Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Although Green would advertise that he had “scour[ed] the [Japanese] empire for the best men obtainable,” he did nothing of the sort. In early 1906 Green instructed Dan Tobey, the Caucasian captain of the Nebraska Indians, to form a team from Japanese immigrants living in California. Led by player-manager Tobey, Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team embarked on a 25-week tour that covered over 2,500 miles through nine Midwestern states as they played about 170 games against town teams and independent clubs. Despite success on the diamond, Green disbanded the club at the end of the season. Two members of the squad, Tozan Masuko and Atsuyoshi “Harry” Saisho, went on to organize their own Japanese barnstorming teams and eventually the Native American tours of Japan.

TOZAN MASUKO AND THE 1921 SUQUAMSSH TOUR

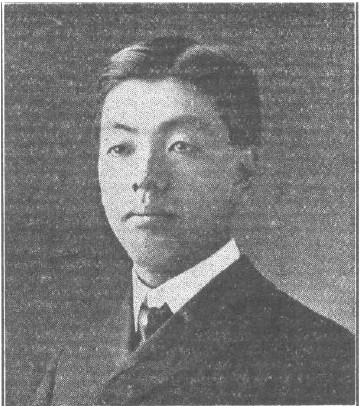

Born in 1881 in the village of Niida in Fukushima Prefecture, Tozan Masuko spent most of his childhood in Tokyo, where he became enamored with the newspaper industry.To further his education, he came to the United States on his own at the age of 14 in 1896. He attended an American high school, where he fell in love with baseball. After graduation, he became a reporter for Shin Sekai in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles to work for the Rafu Shimpo in 1904. There, he joined the newspaper’s baseball team and accompanied Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball team during its 1906 barnstorming tour, occasionally filling in as a utility player or umpire.

Tozan Masuko, promoter of the 1921 Suquamish tour In 1907 the Rafu Shimpo transferred Masuko to Denver, where he decided to create his own professional Japanese barnstorming team. The Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team played 22 games in the summer of 1908 in Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri before rain cut its season short. The following year, he teamed with Harry Saisho to organize another barnstorming team called the Japanese Base Ball Association, which planned to tour the Midwest. That tour also failed after just a few games. During both tours, Masuko tried to promote the teams with exaggerations and outright lies, claiming his squads of local immigrants were “composed of the best nine players from the Japanese Empire … picked from the colleges of Japan … straight from the Orient.” Tozan remained in Denver as editor of the Denver Shimpo for nine more years before moving to Salt Lake City to become editor of the Utah Nippo in 1917. By 1920, however, Masuko had moved to Yokohama, Japan. Drawing on his past experience promoting the Mikado’s and JBBA baseball teams, Tozan decided to become a sports promoter. The endeavor did not go well: A tendency to exaggerate and a lack of scruples got in the way.

Masuko began his new career by bringing Ad Santel and Henry Weber to Japan to “test the relative merits of American wrestling with Japanese jujitsu.” Santel, who is still considered one of the greatest “catch wrestlers” of all time, was the reigning world light-heavyweight champion. Since 1914 he had been wrestling Japan’s top judo champions—often defeating them easily. As a result, he was well-known in Japan. Weber, a 6-foot, 200-pound blond who “looked like a Greek god,” was not Santel’s equal on the mat but was nonetheless a renowned wrestler and Santel’s manager.

A large crowd met Santel and Weber on the pier as they arrived in Yokohama on February 26, 1921. Beneath banners bearing the wrestlers’ names in both English and Japanese, kimono-clad girls presented the visitors with wreaths of flowers and bouquets as the crowd cheered “Banzai!” Tozan accompanied the wrestlers to Tokyo, where they would spend the next week preparing for a match against Japan’s experts from the Kodokan Judo Institute—the school created by the sport’s founder, Jigoro Kano.

Although Masuko had arranged for a prominent judo expert to provide opponents for Santel and Weber, he had never contacted the Kodokan itself. Members of the school were outraged when they heard of Masuko’s plans. Kodokan representatives decreed that any student who took part in the match would be expelled, as “the spirit of Bushido prevents … taking part in any professional show of judo.”

Despite the edict, several judo experts accepted the challenge and wrestled Santel and Weber on March 5 and 6 at Yasukuni Shrine. Sellout crowds of 6,000 to 8,000 attended each day, bringing in an estimated 24,000 yen. After the matches, the wrestlers asked for their 35 percent cut of the gate receipts plus reimbursement for their travel expenses. Masuko, however, claimed that the matches had produced a profit of only 196 yen and promised to pay when cash became available. They next went to Nagoya, where Tozan had arranged two more matches. Despite strong attendance, the wrestlers still did not receive their money. A few days later in Osaka, Santel and Weber refused to enter the ring unless they were paid upfront. Masuko coughed up 300 yen and the matches took place. Noting the large crowds, the wrestlers demanded 1,000 yen prior to the third match. After much wrangling, they eventually accepted a check from a local promoter.

The next morning, when Santel presented the check at the bank, he was told that the promoter had no account, making the check worthless. Returning to the Osaka promoter’s office, Santel learned that Masuko and the local promoter “had drawn on the money due to them until there was nothing left.” The American wrestlers searched in vain for Tozan, who had left Osaka and gone into hiding.

A sympathetic judo expert stepped forward and arranged bouts to raise enough money for Santel and Weber to return to the United States. As he left, Santel told reporters, “Our stay in Japan has been very pleasant in some ways, and we will not carry away the impression that everyone here is bad. … There are swindlers everywhere and we just happen to become connected with two in Japan.” Santel and Weber declined to bring charges against Masuko as legal fees and further time in Japan would have been prohibitively expensive.

A few months later, Tozan once again brought athletes to Japan. This time he returned to the sport he loved and planned to bring the first Native American baseball club to Japan. On July 2, 1921, he arrived in Seattle on board the Fushimi Mara. By the first week of August, Masuko was making arrangements for a team of Suquamish Indians, a group of Native Americans from the western shores of Puget Sound, who had been playing baseball since the late nineteenth century, to accompany him back to Japan. How Masuko learned of the Suquamish team is unknown, but the Bremerton Searchlight reported, “In their efforts to secure an all-Indian ball team for the trip, the promoters have tried out practically every Indian ball team on the coast and the fact that the Suquamish team was finally chosen is a considerable boost for the local players.”

Masuko, who said he was a representative of the Sennichitochi Real Estate and Building Corporation of Osaka, claimed the Suquamish were being invited by Meiji University.

Howard Myrick, who ran the Seattle branch of the A.G. Spalding & Brothers sporting-goods company, was responsible for assembling the squad but the exact relationship between Masuko and Spalding is unknown. The Suquamish players believed their contracts were with Spalding, but, to their chagrin, that would not be the case.

On the morning of August 6, 1921, at 10 A.M., Masuko and the Suquamish ballclub boarded the Alabama Mara at Pier 6 in Seattle and sailed for Yokohama. The squad was an amalgamation of teenage outfielders, semipro veterans, and a legendary pitcher who was called “the Chief Bender of the Northwest.” He threw a fastball, a curve, and a signature pitch called the “clam ball” that would rise as it approached the hitter.Accompanying the Suquamish was a semipro team from Ballard, Washington, that had been renamed the Canadian Stars for the Japanese visit.The teams planned to stay in Japan for about two months.

Cover page of a history of the tour produced by the Suquamish tribe The Canadian Stars and the Suquamish teams were familiar with each other. They met two weeks earlier on July 24, with the Canadian Stars, at that time called the Ballard Merchants, winning, 11-3. The game was started by the main pitchers for both teams. The purveyor of the “clam ball,” 31-year-old Louie George, started for Suquamish, and a future major-league pitcher, 24-year-old Rube Walberg, in a breakout semipro season that would catapult him into professional baseball, started for Ballard. The Suquamish had Arthur Sackman pitching relief and Lawrence Webster was at catcher. The game was previewed in the Seattle Daily Times on July 22, giving us an idea of the perception of the Suquamish style of play: “The Ballard Merchants are going to Suquamish, looking for an easy game, but you never can tell about Indian ball players, as they do not do what is expected of them. In some cases, they break up all kinds of defensive plays by hitting pitch-outs for home runs and making their opponents very uncomfortable.” The Suquamish team was referred to in the same newspaper as being “made up of the best Indian ball players in the Northwest.”

The regular Suquamish team that competed in Seattle area semipro games formed the core of the team that traveled to Japan. Many of their regular players, however, could not travel for two months because of work and stayed home. Enough players stayed behind that the Suquamish had a separate team that continued playing to the end of the semipro season in October.

Seven players on the touring team were members of the Suquamish Tribe: Lawrence “Web” Webster, 22 years old, catcher and outfielder; Charles Thompson, 28, third base and shortstop; Harold “Monte” Belmont, 18, outfield; Roy Loughrey, 20, outfield; Woody Loughrey, 17, outfield; Richard Temple, 18, center field and utility; and Arthur Sackman, 17, outfield and pitcher. The five younger players had experience playing baseball at Indian boarding schools.

Needing to supplement the core of the Suquamish club, the team brought along Louie George and four nonnative players—known as “boomers.” The 31-year-old George was a member of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and, according to the Seattle Daily Times, “is the star of the team. This pitcher is a veteran of many tight pitching duels with Seattle hurlers, having played with Indian teams for years. He also is a heavy slugger and a good outfielder.” Having lost the end of his thumb in a motorcycle accident, George threw an unusual pitch he called a “clam ball.” His nephew Ted George remembered, “It was a pitch that rolled off a shortened thumb at a unique angle … rising as it approached the batter. … It befuddled hitters … and when mixed with a blazing fastball and killer curve became stuff of legend.”

The nonnative “boomers” were 31-year-old Lee “Bill” Rose, first base, catcher, and utility, who became the team’s captain; 27-year-old Roy “Cannon Ball” Woolsey, pitcher, outfield, and coach; 27-year-old James C. Smith, second base; and 23-year-old John Lukanovic, outfield, first base, and pitcher. All four were longtime Northwest Coast semipro players.

Woody Loughrey recalled that during the 16-day trip to Japan, the squad “worked out on the ship, out on the open deck. See it got pretty rough all right” and on “the better days, why, we worked out up there playing catch and running up and down the deck.” Lawrence Webster added, “[T]hat continued rise and fall of those boats itself was awful monotonous, so we started playing catch on the boat. And we started out with about three dozen baseballs so we could keep our arms in shape. By the time we got over there, we had two, just two, not two dozen. That’s all we had [the rest went overboard]. So we hung on to those two and we got over, and we got some new ones that was made over in that country. And there was quite a bit of difference in the baseball. While the size was practically the same, theirs was dead, you’d hit it and it wouldn’t go very far.”

The two clubs arrived in Yokohama on the steamer Alabama at noon on August 22,1921. The Suquamish immediately went to their inn to change into uniforms and then to the Yokohama Park Grounds to practice. “A big gathering of Japanese fans” waited at the park “to give the invading teams an enthusiastic welcome … and to watch their every movement with bat and glove.” The clubs were expected to stay in Japan for two months, playing collegiate teams in Tokyo and touring the country.

Promoter Tozan Masuko bragged to reporters that he had a big tour planned and that his powerful Native American squad would battle against the top Japanese teams. “The tour would start in Tokyo against Meiji University, and then the Indians will play Waseda, Keio, Hosei and Rikkyo Universities, Mita and Tomon Clubs and others. After the Tokyo series, they will go to the Tohoku region with Meiji University, playing in Fukushima, Morioka, Hokkaido, Niigata, and Nagaoka before heading to Kansai for games against Daimai and Star Clubs and other teams. Though depending on circumstances, they are eager to barnstorm even in Shikoku, Kyushu, Manchuria and Korea.”

But none of this was true. Meiji University had neither committed to sponsor the tour nor travel with the visitors to Tohoku. In fact, Masuko had not arranged any games and would put together the schedule on the fly.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

-

Returning Home: The 1914 Seattle Nippon and Asahi Japanese American Tours

by Robert Fitts

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. In this article Robert Fitts discusses the first Japanese American teams to visit Japan.

INTRODUCTION

Between 1890 and 1910, over 100,000 Japanese immigrated to the West Coast of the United States. Many settled in the urban centers of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Within a few years, each of these immigrant communities had thriving baseball clubs. The first known Japanese American team was the Fuji Athletic Club, founded in San Francisco around 1903. A second Bay Area team, the Kanagawa Doshi Club, was created the following year. That same year, newsmen at the Rafu Shimpo organized Los Angeles’s first Issei (Japanese immigrant) team. Other clubs followed in the wake of Waseda University’s 1905 baseball tour of the West Coast. Many players learned the game while still in Japan at their high schools or colleges. Others picked up the sport in the United States. The first Japanese professional club was created the following year by Guy Green of Lincoln, Nebraska. His Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, consisting of Japanese immigrants from Los Angeles, barnstormed throughout the Midwest in the spring and summer of 1906.

Seattle’s first Japanese American club, called the Nippon, was also organized in 1906. Shigeru Ozawa, one of the founding players, recalled that the team was not very good at first and was able to play only the second-tier White amateur nines. By 1907 the team had a large local following. In its first appearance in the city’s mainstream newspapers, the Seattle Star noted that “before one of the largest crowds seen at Woodlands park the D.S. Johnstons defeated the Nippons, the fast local Jap team, by a score of 11 to 5.” In May 1908, before a game against the crew of the USS Milwaukee,the Seattle Daily Times reported that the Nippon “have picked up the fine points of the great national game rapidly from playing the amateur teams around here every Sunday.”

Two months later, the Daily Times featured the team when it took on the all-female Merry Widows. Mistakenly referring to the Nippons as “the only Japanese baseball club in America,” the newspaper reported, “when these sons of Nippon went up against the daughters of Columbia, viz., the Merry Widow Baseball Club, it is a safe assumption that the game played at Athletic Park yesterday afternoon was the most unique affair in the annals of the national game.” Over a thousand fans, including many Japanese, watched the Nippons win, 14-8.

Soon after the game with the Merry Widows, second baseman Tokichi “Frank” Fukuda and several other players left the Nippon and created a team called the Mikado. The Mikado soon rivaled the Nippons as the city’s top Japanese team, with the Seattle Star calling them “one of the fastest amateur teams in the city.” In both 1910 and 1911, the Mikado topped the Nippon and Tacoma’s Columbians to win the Northwest Coast’s Nippon Baseball Championship.

As Fukuda’s love for baseball grew, he realized the game’s importance for Seattle’s Japanese. The games brought the immigrants together physically and provided a shared interest to help strengthen community ties. It also acted as a bridge between the city’s Japanese and non-Japanese population, showing a common bond that he hoped would undermine the anti-Japanese bigotry in the city.

In 1909 Fukuda created a youth baseball team called the Cherry—the West Coast’s first Nisei (Japanese born outside of Japan) squad. Under Fukuda’s guidance, the club was more than just a baseball team. Katsuji Nakamura, one of the early members, explained in 1918, “The purpose of this club was to contact American people and understand each other through various activities. We think it is indispensable for us. Because there are still a lot of Japanese people who cannot understand English in spite of the fact that they live in an English-speaking country. That often causes various troubles between Japanese and Americans because of simple misunderstandings. To solve that issue, it has become necessary that we, American-born Japanese who were educated in English, have to lead Japanese people in the right direction in the future. We have been working the last ten years, according to this doctrine.”

As the boys matured, the team became stronger on the diamond and in 1912 the top players joined with Fukuda and his Mikado teammates Katsuji Nakamura, Shuji “John” Ikeda, and Yoshiaki Marumo to form a new team known as the Asahi. Like the Cherry, the Asahi was also a social club designed to create the future leaders of Seattle’s Japanese community, and forge ties with non-Japanese through various activities, including baseball. Once again the new club soon rivaled the Nippon as Seattle’s top Japanese American team.

THE NIPPON TOUR

During the winter of 1913-14, Mitomi “Frank” Miyasaka, the captain of the Nippon, announced that he was going to take his team to Japan, thereby becoming the first Japanese American ballclub to tour their homeland. To build the best possible squad, Miyasaka recruited some of the West Coast’s top Issei players. From San Francisco, he recruited second baseman Masashi “Taki” Takimoto. From Los Angeles, Miyasaka brought over 30-year-old Kiichi “Onitei” Suzuki. Suzuki had played for Waseda University’s reserve team before immigrating to California in 1906. A year later, he joined Los Angeles’s Japanese American team, the Nanka. He also founded the Hollywood Sakura in 1908. In 1911 Suzuki joined the professional Japanese Base Ball Association and spent the season barnstorming across the Midwest. Miyasaka’s big coup, however, was Suzuki’s barnstorming teammate Ken Kitsuse. Recognized as the best Issei ballplayer on the West Coast, in 1906 Kitsuse had played shortstop for Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, the first professional Japanese club on either side of the Pacific. He was the star of the Nanka before playing shortstop for the Japanese Base Ball Association barnstorming team in 1911. Throughout his career, Kitsuse drew accolades for his slick fielding, blinding speed, and heady play.

To train the Nippons in the finer points of the game, Miyasaka hired 38-year-old George Engel (a.k.a. Engle) as a manager-coach. Although Engel had never made the majors, he had spent 14 seasons in the minor leagues, mostly in the Western and Northwest Leagues, as a pitcher and utility player. Miyasaka also created a challenging schedule to ready his team for the tour. They began their season with games against the area’s two professional teams from the Northwest League. On Sunday, March 22, they lost, 5-1, to the Tacoma Tigers, led by player-manager and future Hall of Famer Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity. The following Sunday the Seattle Giants, which boasted seven past or future major leaguers on the roster, beat them 5-1. Despite the one-sided loss, the Seattle Daily Times noted, “the Nippons … walked off Dugdale Field yesterday afternoon feeling well satisfied with themselves for they had tackled a professional team and had made a run.”

In April 1914, Keio University returned for its second tour of North America. After dropping two games in Vancouver, British Columbia and a third to the University of Washington, Keio met the Nippons on April 9 at Dugdale Park in what the Seattle Daily Times called “the world’s series for the baseball championship of Japan.” On the mound for Keio was the great Kazuma Sugase, the half-German “Christy Mathewson of Japan,” who had starred during the school’s 1911 tour. The team also included future Japanese Hall of Famers Daisuke Miyake, who would manage the All-Nippon team against Babe Ruth’s All-Americans in 1934, and Hisashi Koshimoto, a Hawaiian-born Nisei who would later manage Keio.

Nippons manager George Engel was in a quandary. His usual ace Sadaye Takano was not available and as Keio would host his team during its coming tour of Japan, he needed the Nippons to prove they could challenge the top Japanese college squad. Engel reached out to William “Chief’ Cadreau, a Native American who had pitched for Spokane and Vancouver in the Northwestern League, one game for the 1910 Chicago White Sox, and would later pitch a season for the African American Chicago Union Giants. Pretending that he was a Japanese named Kato, Cadreau started the game. According to the Seattle Star, “Engel was very careful to let the Keio boys know that Kato, his pitcher, was deaf and dumb. But later in the game Kato became enthused, as ball players will, and the jig was up when he began to root in good English.” Nonetheless, Cadreau handled Keio relatively easily, striking out 13 en route to a 6-3 victory.

Throughout the spring and summer, the Nippons continued to face the area’s top teams, including the African American Keystone Giants, to prepare for the trip to Japan. Yet in their minds, the most important matchup was the three-game series against the Asahi for the Japanese championship. The Nippons took the first game, 4-2, on July 12 at Dugdale Park but there is no evidence that they finished the series. Not to be outdone by their rivals, the Asahi also announced that they would tour Japan later that year. Sponsored by the Nichi-nichi and Mainichi newspapers, the Asahi would begin their trip about a month after the Nippons left for Japan.

The Nippon left Seattle aboard the Shidzuoka Maru on August 25. Their departure went unreported by the city’s newspapers as international news took precedence. Germany had invaded Belgium on August 4, opening the Western Front theater of World War I. Throughout the month, Belgian, French, and British troops battled the advancing Germans. Just days before the ballclub left for Japan, the armies clashed at Charleroi, Mons, and Namur with tens of thousands of casualties. On August 23, Japan declared war on Germany and two days later declared war on Austria.

After two weeks at sea, the Nippon arrived at Yokohama on September 10. The squad contained 11 players: George Engel, Frank Miyasaka, Yukichi Annoki, Kyuye Kamijyo, Masataro Kimura, Ken Kitsuse, Mitsugi Koyama, Yohizo Shimada, Kiichi Suzuki, Sadaye Takano, and Masashi Takimoto. Accompanying the ballplayers was the team’s cheering group, consisting of 21 members and led by Yasukazu Kato. The group planned to attend the games to cheer on the Nippon and spend the rest of their time sightseeing.

As the Shidzuoka Maru docked, a group of reporters, Ryozo Hiranuma of Keio University, Tajima of Meiji University, and a few university players came on board to welcome the visiting team. The group then took a train to Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, where they were met by the Keio University ballplayers at 2:33 P.M. The Nippon checked in at the Kasuga Ryokan in Kayabacho while the large cheering group, which needed two inns to accommodate them, settled down at the Taisei-ya and Sanuki-ya.

Only two hours later, the Nippon arrived at Hibiya Park for practice. Not surprisingly, after the voyage they were not in top form. The Tokyo Asahi noted, “Even though the Seattle team is composed of Japanese, their ball-handling skills are as good as American players, and … their agile movements are very encouraging. … They hit the ball with a very free form, but yesterday, they did not place their hits very accurately, most likely due to fatigue. … The Seattle team did not have a full-fledged defensive practice with each player in position, so we did not know how skilled they were in defensive coordination, but we heard that the individual skills of each player were as good as those of Waseda and Keio. In short, the Seattle team has beaten Keio University before, so even though they are Japanese, they should not be underestimated. On top of that, they have good pitching, so games against Waseda University and Keio University are expected to arouse more than a few people’s interest, just like the games against foreign teams in the past.”

The Nippon would stay in Japan for almost four months, but the baseball tour itself consisted of just eight games—all played during September against Waseda and Keio Universities. The players spent the rest of the time traveling through their homeland and visiting family and friends.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

-

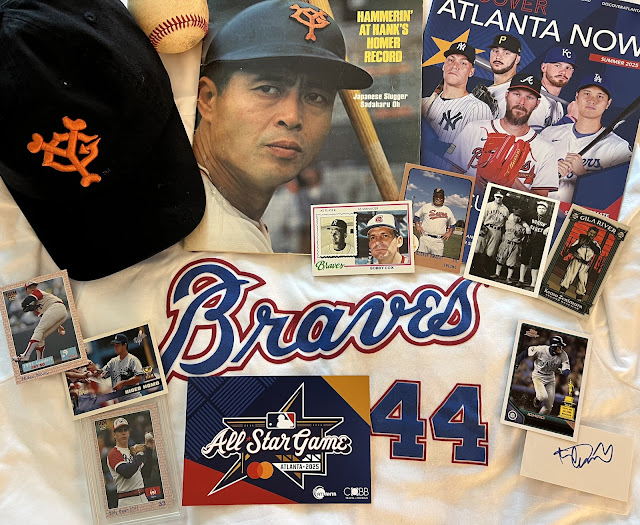

Baseball’s Bridge Across the Pacific Returns to MLB’s All-Star Village

by Bill Staples, Jr.

The Baseball’s Bridge Across the Pacific exhibit made a powerful return at the 2025 MLB All-Star Game in Atlanta, drawing thousands of fans to Truist Park from July 12–15. Presented by the Nisei Baseball Research Project with Major League Baseball, the Japanese American Citizens League, and MLB’s Diverse Business Partners program, the showcase celebrated the enduring legacy of Japanese American baseball, U.S.-Japan baseball relations, and its influence on the global game. This year’s edition featured new Georgia connections in Japanese baseball, rare artifacts, tributes to baseball pioneers Hank Aaron and Sadaharu Oh, and thought-provoking art by Ben Sakaguchi, while honoring the late MLB Ambassador Billy Bean. With its blend of history, culture, and human stories, the exhibit strengthened its call for a permanent exhibit in a museum and teased plans for the 2026 All-Star Game in Philadelphia during America’s 250th birthday celebration.

Read the full story here

https://billstaples.blogspot.com/2025/07/baseballs–bridge-across-pacific-exhibit.html

-

MID-DECADE MILESTONES IN U.S.–JAPAN BASEBALL RELATIONS (1875–2025)

by Bill Staples, Jr.

A 150-Year Journey Through the Game That Bridges Nations

Ichiro Suzuki’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on July 27, 2025 is a milestone worth celebrating—and an opportunity to reflect on the progress of U.S.–Japan baseball relations. From Ichiro’s enshrinement to the sandlot games played by Japanese school children during the 1870s, the history of baseball between the U.S. and Japan is a rich narrative of cultural exchange, perseverance, diplomacy, and innovation.

With that in mind, I thought it would be fun to use Ichiro’s 2025 achievement as a springboard to explore key mid-decade milestones (years ending in five) in the U.S.–Japan baseball journey. Let’s look at how the sport evolved from a foreign curiosity into a shared national passion—and ultimately, a bridge between two nations.

Let’s begin in the present and work our way backward.

NOTE: The full version of this article with all illustrations and links is available on Bill Staples, Jr’s blog, International Pastime.

https://billstaples.blogspot.com/2025/04/mid-decade-milestones-in-usjapan.html

2025

Ichiro Suzuki was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2025, receiving 393 out of 394 votes (99.75%) in his first year on the ballot. This made him the first Japanese-born position player elected to Cooperstown, though he fell one vote shy of unanimous selection—a distinction held by Mariano Rivera in 2019. In anticipation of his enshrinement, the Hall of Fame created a new exhibit titled Yakyu | Baseball: The Transpacific Exchange of the Game. The exhibit will open in July 2025 and remain on display for at least five years. Learn more at: https://baseballhall.org/yakyu. 2015

Ichiro, now with the Miami Marlins, begins symbolically “passing the torch” to Shohei Ohtani, who is in the second year of his professional career with the Nippon Ham Fighters in Japan. The 2015 season marks Ichiro’s first appearance as a pitcher, setting the stage for a rare and unexpected future Hall of Fame connection between Ichiro and Ohtani—two Japanese-born players who both pitched and hit a grand slam during their MLB careers. Ichiro hit just one grand slam, while Ohtani has hit three (as of this post), and intriguingly, all of them against the Tampa Bay Rays.2005

Tadahito Iguchi becomes the first Japanese-born player to compete in and win a World Series, contributing to the Chicago White Sox’s historic run. (Note: Hideki Irabu received a World Series ring as a member of the 1998 and 1998 New York Yankees but did not play in any postseason games). Check out Iguchi’s SABR Bio.1995

Hideo Nomo joins the Los Angeles Dodgers, earning Rookie of the Year, an all-star game start, and igniting “Nomomania.” His success breaks open the modern pipeline between NPB and MLB and reshapes the perception of Japanese players on the global stage. Check out Nomo’s SABR Bio.1985

Pete Rose breaks Ty Cobb’s all-time hit record using a Mizuno bat. After visiting Japan in 1978, Rose teamed up with sports agent Cappy Harada to sign a sponsorship deal with Mizuno in 1980. Rose’s partnership with Mizuno marked a significant moment in sports history, symbolizing Japan’s growing influence in global sports and helping to establish Japanese manufacturers as credible names in American dugouts and MLB clubhouses.1975

The Chunichi Dragons, led by manager Wally Yonamine, and the Yomiuri Giants, led by manager Shigeo Nagashima, conduct spring training in Florida. Meanwhile, American-born manager Joe Lutz and Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn contribute to Japanese baseball by joining the Hiroshima Carp. Lutz becomes the second U.S.-born manager in NPB history after WWII, following Hawaii-native Yonamine. However, Lutz’s time with the Carp is short-lived, as he steps down just weeks into the new season. Spahn continues his role with the Carp and states that he prefers working in Japan compared to the U.S.

Joe Lutz, Hiroshima Carp 1975 1965

Masanori Murakami finishes his rookie season with the San Francisco Giants after debuting in 1964, becoming the first Japanese-born player in MLB. His success inspires generations of Japanese players to dream of American stardom.

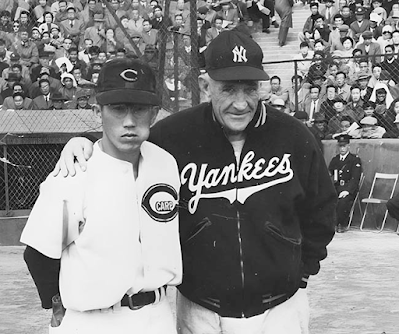

Masanori Murakami 1955

After a season in the minor leagues and facing lingering post–World War II anti-Japanese sentiment, California native Satoshi “Fibber” Hirayama chose to continue his professional baseball career in Japan, signing with the Hiroshima Carp. That same season, the New York Yankees toured Japan, and afterward, former Japanese pitching star and Hawai‘i native Bozo Wakabayashi was hired as a scout for the team. However, Yankees manager Casey Stengel resisted the idea of signing Japanese players, citing concerns about adding new talent to an already talent-heavy roster.

Fibber Hirayama with Casey Stengel, 1955 1945

In the aftermath of World War II, baseball became a source of healing and pride for Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated behind barbed wire. At the Gila River camp in Arizona, the Butte High Eagles stunned the defending state champions, the Tucson High Badgers, with an 11–10 extra-innings victory. Coach Kenichi Zenimura called it “the greatest game ever played at Gila.” After graduating, Eagles second baseman Kenso Zenimura relocated to Chicago, where he attended the East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park and watched Kansas City Monarchs standout Jackie Robinson during his lone season in the Negro Leagues.

Kenichi Zenimura at Gila River in 1945 1935

The founding of the Tokyo Giants paved the way for the launch of the Japanese Professional Baseball League in 1936. During the team’s groundbreaking U.S. tour, four players — pitchers Victor Starffin and Eiji Sawamura, infielder Takeo Tabe, and outfielder Jimmy Horio — attracted interest from American professional clubs and may have received contract offers. However, the 1924 Immigration Act rendered Japanese-born players ineligible to sign with U.S. teams. Only one player—Hawaii-born Horio—was eligible under U.S. law. He signed with the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League for the 1935 season but returned to Japan the following year to join the Hankyu Braves in the new professional league.

Jimmy Horio with Sacramento in 1935 1925

Sponsored by the Osaka Mainichi newspaper, a semipro team called Daimai was formed and sent on tour in the United States, where they faced American universities and semi-pro clubs, including the Japanese American Fresno Athletic Club (FAC). In early September, the FAC played a doubleheader at White Sox Park in Los Angeles—the first game against Daimai, and the second against the L.A. White Sox, the premier Negro Leagues team in Southern California. Behind the strong pitching of Kenso Nushida, FAC edged out the White Sox 5–4, setting the stage for rematches in 1926 and parallel tours of Japan in 1927. White Sox manager Lon Goodwin rebranded his team as the Philadelphia Royal Giants for the Japan tour, ushering in a new era of international baseball exchange.

Catcher O’Neal Pullen and pitcher Jay Johnson of the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1927. Negro Leagues Baseball Museum 1915

The Hawaiian Travelers, a barnstorming team made up of Chinese and Japanese Americans from the Hawaiian Territories, toured the U.S. mainland in the early 20th century. Two Japanese players, Jimmy Moriyama and Andy Yamashiro, joined the team under assumed Chinese identities, playing as “Chin” and “Yim.” The Travelers impressed fans and opponents alike with victories over top Negro League clubs such as the Lincoln Giants and Brooklyn Royal Giants—both teams now designated as major league caliber by SABR. After a return tour, Yamashiro, still using the name Andy Yim, signed with the Gettysburg Ponies of the Class D Blue Ridge League in 1917, quietly becoming the first Japanese American to join an integrated professional team—though history recorded him only under his adopted identity. Meanwhile, an Osaka newspaper, Asahi Shinbun, sponsors a national tournament for high school teams that eventually becomes one of the most popular sporting events in Japan (known today as the Koshien Tournament).

The Hawaiian Travelers in 1914 1905

The 1905 Waseda University baseball tour was the first time a Japanese college team traveled to the United States to compete, playing 26 games along the West Coast and finishing with a record of 7 wins and 19 losses. The team was led by Abe Isō, a Waseda professor, Unitarian minister, and politician who saw baseball as a powerful tool for international exchange and cultural diplomacy. Although Waseda struggled on the field, the tour was a landmark moment in U.S.–Japan relations, helping to lay the groundwork for future athletic and cultural connections between the two nations. Meanwhile, John McGraw of the New York Giants gave a tryout to a Japanese outfielder known as “Sugimoto.” However, shortly after Sugimoto’s arrival at spring training, discussions in the press about enforcing the color line surface. In response, Sugimoto chose to leave the tryout of his own accord.

1905 Waseda University Baseball 1895

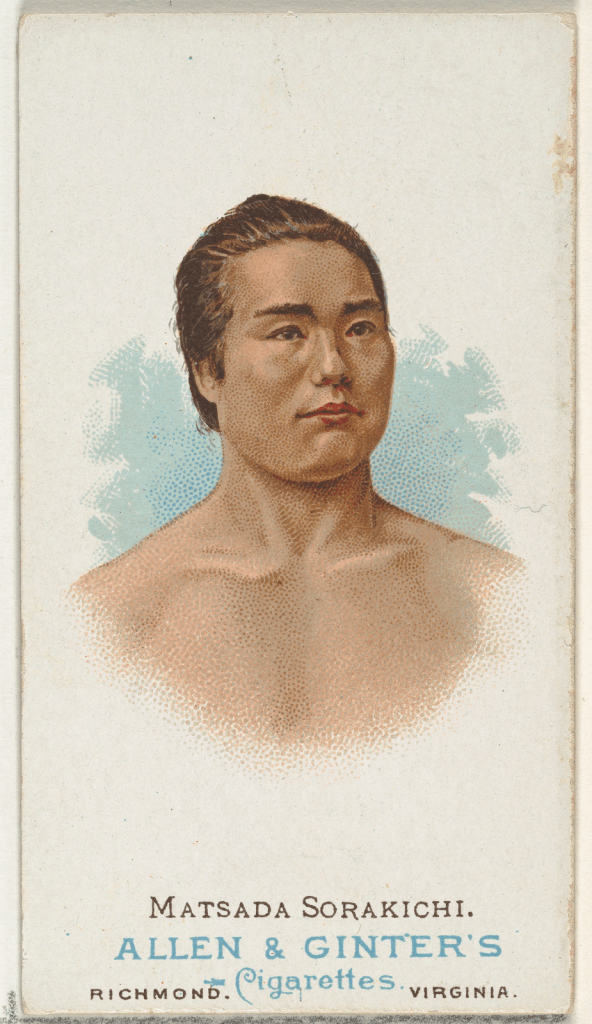

Dunham White Stevens, the American Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Washington, was described as “a baseball crank” and persuaded Japanese Minister Shinichiro Kurino to join him at several games. This gesture reflected one of the earliest examples of diplomatic engagement through sport. Meanwhile, Japanese American ballplayers were competing in amateur leagues in Chicago, and by 1897, a promising outfielder—identified in the press only as the cousin of wrestler Sorikichi Matsuda—was reportedly scouted by Patsy Tebeau, manager of the major league Cleveland Spiders.

1887 Allen & Ginter trading card of Sorakichi Matsuda 1885

Sankichi Akamoto, a young Japanese acrobat and baseball enthusiast, played the game in America, blending cultural performance with sport. His presence foreshadowed the dual role many Japanese athletes would later assume—as both competitors and cultural ambassadors. Around the same time, at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, Japanese student Aisuke Kabayama competed on the school’s tennis and baseball clubs, eventually earning a spot on the varsity baseball team the following season. His participation is believed to be the earliest recorded instance of a Japanese-born player in U.S. college baseball.

The Akimoto Japanese Troupe, circa. 1885. Robert Meyers Collection 1875

The seeds of Japanese baseball began to take root in the early 1870s, as people of Japanese ancestry played the game on both sides of the Pacific. In 1873, Albert G. Bates, an American teacher in Tokyo, organized what’s considered the first formal school-level baseball game in Japan. According to Japanese sports historian Ikuo Abe, the game occurred on the grounds of the Zojiji Temple in Tokyo (image below). Tragically, in early 1875, Bates died at just 20 years old from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning while visiting a public bathhouse.

“View of Zōjōji Temple at Shiba,” by Yorozuya Kichibei (1790-1848), Minneapolis Institute of Art -

Solving the Mystery of Togo Hamamoto

by Rob Fitts

Originally published on RobFitts.com February 15, 2021

The history of early Japanese American baseball is still being discovered. There is so much we do not know. Mainstream, English-language newspapers rarely covered Japanese American daily life or sport. When these newspapers did mention Japanese immigrant baseball, the articles were often garbled—full of misspellings, factual errors, and sometimes overt bigotry. On top of this, early twentieth century sportswriters enjoyed telling an entertaining story more than report fact. Piecing together history from these articles is challenging as most of the reports cannot be taken at face value but instead need to be confirmed by independent sources. As an example, let’s examine the story of Togo Hamamoto.

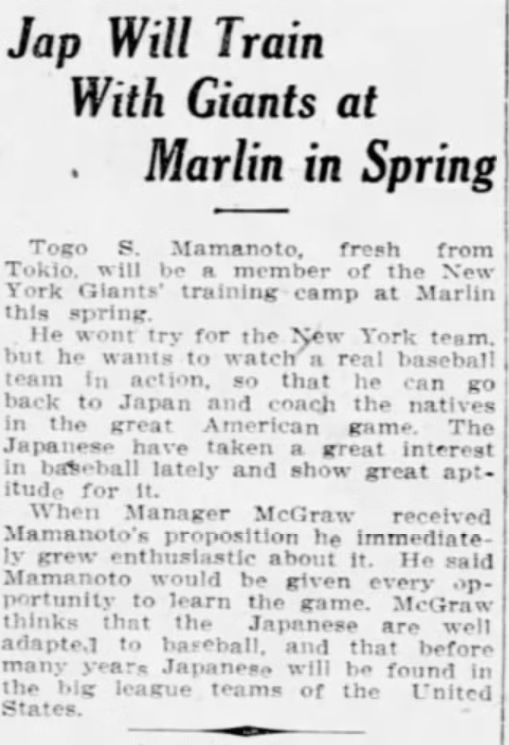

In mid-January 1911, an intriguing article ran on the sports pages across the United States. On January 17th, New York Giants manager John McGraw announced that Togo S. Hamamoto of Tokyo would be joining the team at Marlin Springs, Texas, to observe American “scientific baseball.”

A press release noted that Hamamoto, “who has the backing of a number of influential citizens of Tokyo, . . . will devote his time to mastering the game.”[1] “His backers plan to add professional baseball in their own country.”[2] “McGraw plans to do all in his power to spread the gospel of the game in foreign lands,” the release continued. He “is prophesying that some day [sic] a real world’s championship will be played with the United States and Japan as rivals.”[3] Newspapers across the country, from large-market dailies to bi-weekly rags in rural villages, reprinted the announcement.

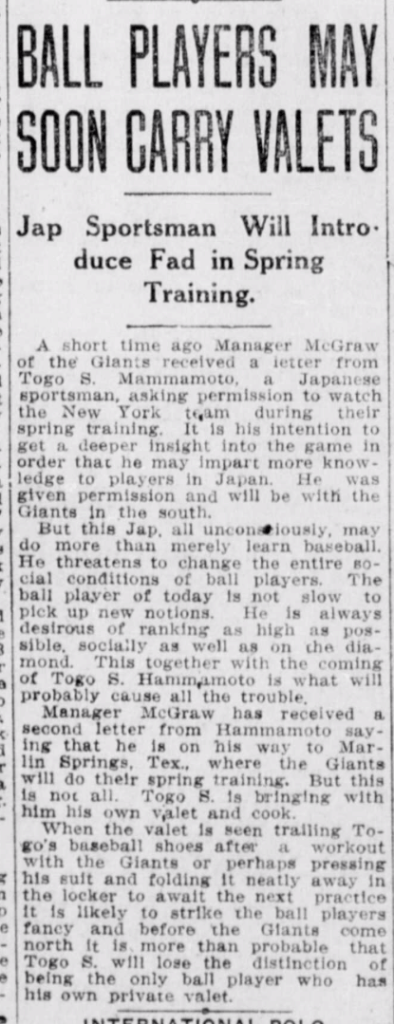

About a month later, Hamamoto was in the news again. This time, reporters had transformed him from an observer into a player receiving a tryout. “Togo is a star player among the Japs, and will work out daily,” reported the Chronicle-Telegram of Elyria, Ohio. “He may play on the second team.”[4] But of more interest to the writers were reports of Hamamoto bringing his valet and personal cook to training camp.

He “may do more than merely learn baseball. He threatens to change the entire social conditions of ball players,” joked an anonymous writer. “When the valet is seen trailing Togo’s baseball shoes after a workout with the Giants or perhaps pressing his suit and folding it neatly away in the locker to await the next practice, it is likely to strike the ball players’ fancy and before the Giants come north it is more than probable that Togo S. will lose the distinction of being the only ball player who has his own private valet.”[5] Another writer worried, “McGraw fears a valet oiling Togo’s shoes and fanning him between innings, may cause the Giants to insurge [sic] and ask for the same treatment.”[6]

On March 9, the sports editor of the New York Times asked, “Where is Togo Hamamoto, the Japanese athlete, who was going to train with the New York Giants at Marlin Springs? Togo burned up the cables getting permission from Manager McGraw to get inside information on training a baseball team, and McGraw gave him permission to join the camp. But he hasn’t appeared, and nothing has been heard from him.”[7] The Giants began practicing in Marlin’s Emerson Park on February 20 and stayed until March, practicing in Emerson Park. Reports from the Giants’ spring training camp fail to mention Hamamoto and newspaper articles do not provide a reason for his absence.

When I wrote the first draft of Issei Baseball in 2018, I wondered if the story was a hoax dreamed up by a bored sportswriter yearning for the start of the baseball season. My searches of immigration records found no man named Hamamoto arriving from Japan in 1911, plus his name does not appear in Japanese baseball histories. On top of that, his name is suspiciously similar to Irving Wallace’s fictional character Togo Hashimura, the Japanese “school boy” whose book of fictitious letters describing life in America had become a best seller in 1909. I concluded that the articles written about Hamamoto attending spring training were a hoax written for amusement.

That changed in early 2019 when I received a copy of Tetsusaburo “Tom” Uyeda’s previously classified FBI file. Uyeda, who had played on Guy Green’s 1906 Japanese Base Ball Team and the 1908 Denver Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team, was unjustly convicted in 1942 by the U.S. Alien Enemy Hearing Board as a Japanese spy. During his appeal, Uyeda explained; “In the Spring of 1912, I received a letter from one Mr. Hamamoto who asked me to come over to St. Louis, Missouri, to assist in organizing a baseball team.”[8]

Refocusing my research on St. Louis, I found a Togo S. Hamamoto listed in the city directory as valet working for Hugh Kochler, a wealthy brewer. Born Shizunobu Hamamoto in Nagasaki on December 25, 1884, he arrived in Seattle on the SS Shimano Maru on April 22, 1903. He made his way to St. Louis in 1906 and began working as a valet while reporting on Major League baseball for the Nagasaki-based newspaperSasebo. He attended four or five games per week and became friendly with a number of the players, including Cristy Mathewson, Lou Gehrig, and Babe Ruth [9].

But did Hamamoto attend the Giants’ spring training in 1911? There was no evidence that he had until June 2020 when Robert Klevens, owner of Prestige Collectibles and an authority of Japanese baseball memorabilia, found this postcard.

The picture shows Hamamoto wearing a Giants uniform made between 1909 and 1910 (the team used a different logo on their sleeve in 1908 and switched to pinstripes in 1911). The solid stocking pattern was used by the Giants only in 1909, but we do not know if the Giants issued these to Hamamoto or if he wore his own stockings.

(Illustration from Baseball Uniforms of the 20th Century by Marc Okkonen

As new uniforms were expensive and teams did not have large budgets, it was common for players to practice in uniforms from previous seasons. This picture from spring training in 1912, for example, shows Giants players in various uniform styles.

I have not been able to locate enough pictures of Emerson Park to confirm if the photograph of Hamamoto was taken there, but the wooden fence in the photograph is similar to the fence surround the ballpark. Efforts to identify the Mr. S noted on the back has been fruitless.

So even though the postcard does not prove that Hamamoto attended the Giants spring training in 1911, it is likely that the newspaper stories were partly accurate and that he eventually arrived. Hamamoto’s time with the Giants, however, did not lead to a professional baseball league in Japan. Unsuccessful attempts to create a pro circuit did not begin until 1920s and it was not until the creation of Japanese Baseball League in 1936 that Japan would have a stable professional league.

Hamamoto would eventually turn his back on baseball. A few years later, he was in the stands watching his home-town Browns battle Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators when a St. Louis batter popped out in a key situation. “Some of the people behind me, and one of them was a lady, used such language—oh, it was so bad that I decided baseball did not always contain the three cardinal principals which I think a sport should have—Dignity, Honesty, and Humor. Since then I have not gone to ball games.”[10]

Around 1916, while still working as a valet for Kochler, Hamamoto took up golf. He played at every opportunity and soon mastered the sport. In 1929, he won St. Louis’s Forrest Park Golf Club’s championship and went on to play in several national amateur championships. Upon his father’s death in 1933, he returned to Nagasaki to inherit the estate. At the end of World War II, he became an interpreter for the police in Haiki, Japan.[11] The year of his death is unknown.

[1]Salt Lake Telegram, January 17, 1911, 7.[2] Akron Beacon Journal, January 18, 1911, 8.

[3]Salt Lake Telegram, January 17, 1911, 7.

[4]Chronicle-Telegram, February 23, 1911, 3.

[5]Winnipeg Tribune, February 24, 1911, 7.

[6]Elyria Chronicle-Telegram, February 23, 1911, 3.

[7]New York Times, March 9, 1911, 12.

[8] Tetsusaburo Uyeda to Edward J. Ennis, January 3, 1944. World War II Alien Enemy Detention and Internment Case Files, Tetsusaburo “Thomas” Uyeda, Case 146-13-2-42-36.

[9]St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1929, 19.

[10]St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1929, 19.

[11]St. Louis Star and Times, December 4, 1945, 22.

-

The First Japanese Professional Game Took Place in …. Kansas?

by Rob Fitts

The first Japanese professional baseball game took place not in Tokyo, not in Osaka, or even in Japan, but in a tiny town in Northeastern Kansas.

In 1906 much of United States was enthralled by Japan and all things Japanese. Japan had just emerged as the improbable victor in the Russo-Japanese War and the year before the Waseda University baseball club had toured the West Coast. Guy W. Green, the owner of the Nebraska Indians Baseball Club, decided to capitalize on the fad by creating an all-Japanese baseball team to barnstorm across the Midwest. It would be the first Japanese professional team on either side of the Pacific.

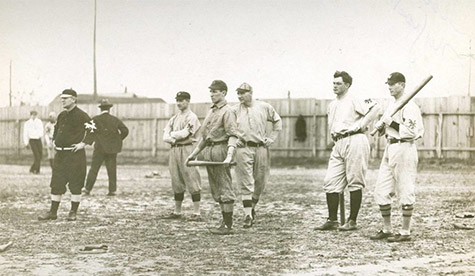

Guy W. Green (center) with his Nebraska Indians Base Ball team ca. 1905 The early twentieth century was the heyday of barnstorming baseball. Independent teams crisscrossed the country playing in one-horse towns and large cities. There were all female teams, squads of only fat men, clubs of men sporting beards, and teams consisting of “exotic” ethnicities. These independent squads were often called “semi-professional” to differentiate them from teams in Organized Baseball (clubs formally associated with Major League Baseball), but they were professional enterprises. The teams signed players to contracts, paid salaries during the season, provided transportation and housing on the road, charged admission to games, and were intent on turning a profit.