By Carter Cromwell

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates – Birthed just three and a half years ago, Baseball United took a major step toward adulthood this November.

Formed to bring professional baseball to a region with little exposure to the game, Dubai-based Baseball United had staged a two-game showcase in November 2023 involving several former Major League Baseball (MLB) standouts; then the Arab Classic a year later that matched the national teams of nine countries; and an exhibition series in February 2025 between two of its teams.

But when Karan Patel of the Mumbai Cobras threw a fastball to Pavin Parks of the Karachi Monarchs at 8:21pm on November 14, it marked a significant milestone. It was the first pitch of the first game of the first regular season of the first professional baseball league representing the Middle East and South Asia. And it took place in the first and only pro baseball facility in the region – Baseball United Ballpark.

Parks, by the way, hit that first pitch over the left field fence for a home run, and he hit another in the ninth inning as part of a five-run rally that lifted Karachi to a 6-4 victory.

“We’ve visualized this for three years, and – as I stand before you now – it looks even better than in my dreams,” Baseball United co-founder and CEO Kash Shaikh told the crowd of approximately 3,000 prior to the opening game.

Former major-leaguer Mariano Duncan, who manages the Mumbai team and has been with the league from early on, said, “We’ve finally brought a baseball season to Dubai. There’s a lot more work to do, but I’m happy we’ve been able to take this big step.”

The November 14 contest began a one-month season in which each of the four teams will play nine games, followed by a best-of-three series for the championship. All the clubs – the Arabia Wolves and Mid East Falcons, along with the Cobras and Monarchs – play at Baseball United Ballpark with games broadcast in several countries and streamed live on YouTube.

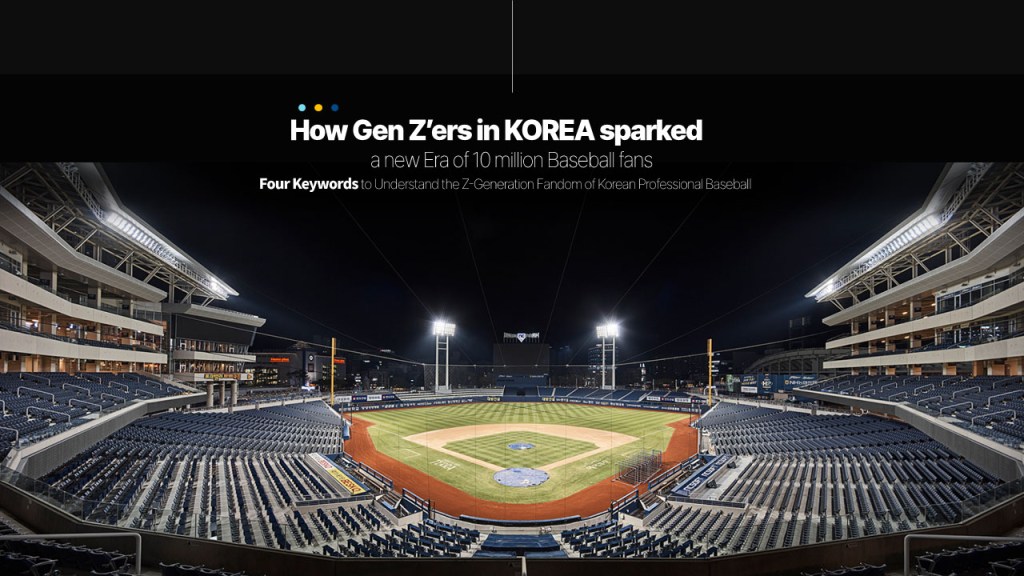

The league is attempting the yeoman’s task of germinating the game in what might seem like infertile soil – creating something from scratch, as Shaikh has said. To do this, Baseball United has worked to develop the fan experience – something always important but especially so in this case since the game is unknown to a large portion of the potential fan base.

“It’s a long process to really grow the fan base,” Shaikh said. “We’re taking the game where most people don’t know it. This is the most under-developed region as far as baseball goes, so this is going to take some time. We have to do is make sure people enjoy the overall experience.”

John Miedrich, a co-owner and executive vice president of operations, concurred: “We’re talking about teaching the game, of course, but it’s just as important to teach the fan experience. Baseball is so new to the region that most people don’t have an understanding of the game, but if they have a good overall experience when they attend, there’s a chance they’ll come back.”

Similar to games in Japan and Korea, the games feature cheering sections on each side with people waving towels, as well as bands in the left field and right field stands. There is music throughout, a dance team that sometimes performs between innings, kids racing mascots around the bases between innings once per game, and a youngster enthusiastically announcing “Play Ball” to the crowd. And perhaps the most unique innovation is having each starting pitcher enter the game from the bullpen while riding a camel.

The league also features some new rules:

- If a game is tied after nine innings, a home-run derby, or swing-off, will decide the winner. Each team’s nominated player gets 10 swings to hit as many home runs as possible. If the hitters tie, a sudden-death swing-off occurs.

- Each team has a designated runner it can use once per inning, without the man he replaces being removed from the game.

- As many as three times in a game, the team at bat can declare a “Money Ball”. A bright yellow ball replaces the regular white one, and if the player at bat hits a home run, it doubles the number of runs scored. If the batter is walked or hit by a pitch, the Money Ball rolls over to the next batter.

- “Fireball” – If the team in the field calls a fireball and the current batter strikes out, the inning is over, regardless of how many outs there were at the time. Each team is allowed three fireballs per game.

“We started the fireball this year because people said we had rules to help the teams at bat but nothing to help the pitchers,” Shaikh said. “Some people like the rules, and others don’t, but we think this makes us stand out a little more.”

Antonio Barranca, an American and catcher for the Arabia Wolves who played two years in the Atlanta Braves organization, said, “It’s kind of crazy – but fun – to see some things like the new rules and pitchers riding on camels. It makes the league a little different and helps them get their brand out.”

At a media event the day before the opener, Shaikh pointed out left and right fields to the media members and had to make it clear that the second baseman doesn’t actually position himself on the base. He also explained the “charge” fanfare and the seventh-inning stretch during which fans sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game”. Then he invited them to play a game of catch with the likes of co-owner and former major league catcher Robinson Chirinos and others.

Likewise, the television commentators sometimes explained situations likely not understood by those new to the game. For example: why there is no need to tag a runner on a force play.

The population of Dubai is approximately 90 percent expatriate, and more than a few residents come from baseball-playing countries such as the U.S., Canada, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and others. Baseball also has some similarities to cricket, which has a large, rabid following in countries like India and Pakistan.

“To spread the word, we’ve been talking a lot with people from the various embassies, the Philippine softball family; the cricket people from Australia, New Zealand, India, and Pakistan; and others,” Miedrich said.

The league has, in part, constructed the team rosters with an eye toward attracting fans of different nationalities. A check of the rosters, shows that, while many of the players are American, there are players born in 23 other countries – from Europe, North America, South America, Central America, the Caribbean, South Asia, and East Asia.

Seven players have MLB experience, the most prominent being outfielder Alejandro de Aza of the Mid East Falcons. More than 20 players have been in the minor league organizations of MLB teams; more than 40 have played in independent leagues; and at least seven have played in European leagues.

Shaikh pointed out that “Mumbai has two players from the Philippines [shortstop Lord De Vera and outfielder Ian Mercado], as well as six from India. Karachi has four Pakistanis – look out for Musharraf Khan, a 6-7 pitcher – and there are 14 Japanese players on the Mid East Falcons.”

The Japanese contingent includes former Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) stars Munenori Kawasaki, Hiroyuki Nakajima, and Shuhei Fukuda; others with NPB experience; and Manato Tanai, an 18-year-old shortstop who was the fifth pick in the 2024 NPB draft and is considered one of the Yokohama DeNA BayStars’ better prospects. Kawasaki is 44 years old, Nakajima 43, and Fukuda 36. Kawasaki spent five seasons in MLB with Seattle, Toronto, and the Chicago Cubs.

“The Falcons are quickly becoming a fan favorite in Japan,” Shaikh said on a recent game broadcast,[i]“with 60 percent of the roster composed of Japanese. It’s a great mix of veterans and young prospects.”

Three other Japanese – outfielder Yo Kanahara and pitchers Yudai Mizushina and Shotaro Nakata – earned their spots by winning a reality show competition produced by Japan’s Tokyo Broadcast System (TBS) network, which also broadcasts the games.

“The show started with 300 players, and just the three were chosen,” according to Chiharu Yamamura, Baseball United’s senior director of Japan Operations. “I worked with TBS on the series, and they want to do it again next year – maybe even export the show format to other countries.”

Several of the Japanese played leading roles in Mid East’s first game November 19. Kazuki Yabuta and Shotaro Kasaharacombined with Mizushina and former major leaguer Severino Gonzalez to pitch the league’s first no-hitter in a 2-0 victoryover Karachi. Kawasaki had two hits, including a double that led to the Falcons’ first run, and Kanahara scored both runs as the designated runner.

Through December 2, Kawasaki and Nakajima were each averaging .353 and Fukuda .188. Tanai showed off a good arm, but had just two hits in his first 15 at bats before going 3-3 with two walks against Mumbai on December 2. Yabuta had an 0.63 earned-run mark after 14 1/3 innings along with 23 strikeouts and four walks, and Kasahara had pitched 2 2/3 scoreless innings. Haru Yoshioka, a 19-year-old BayStars prospect, had a 2.45 ERA through 3 2/3 innings, and Shuto Sakurai, who has pitched in NPB for both Yokohama and Rakuten, was 1-0 and had struck out nine batters in six innings.

“Kawasaki has been incredible – such an ambassador for the game,” Shaikh said. “He’s 44 now but still in great shape, and I see him at the cricket fields [next to the ballpark] teaching the young kids.”

Mid East manager Dennis Cook, a former MLB pitcher who also runs the Polish national team with Arabia manager John McLaren, said Kawasaki “is a little long in the tooth, but he can still play. He, Nakajima, and Fukuda are fundamentally sound, won’t strike out a lot, and will put the ball in play.”

Baseball United is betting that a long-term, grass-roots approach will eventually bear fruit, but getting to this point has been no easy task.

“This whole project was exciting because it was an empty canvas here, but it was daunting because it was an empty desert,” Shaikh said. “I had an idea of [the size of the task] beforehand but didn’t know the level it would take in training and so forth. And I didn’t realize how much government relations there was to do – with the federations, tourism councils, and government officials. That’s been a crazy part of the journey.

“I knew it would be the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but it’s been even harder.”

Duncan, the Mumbai manager, said he’s been associated with Baseball United since the early days and that he got Hall-of-Famer Barry Larkin involved. As a co-founder, Larkin is senior vice president and leads player development strategies and initiatives.

“I was asked to help find investors, and Barry was the first person I thought about,” Duncan said. “Knowing that he’d been involved internationally as coach of the Brazil WBC (World Baseball Classic) team, I thought he’d be the perfect guy.”

For his part, Larkin said he had been to India a number of years ago as part of a government program during the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations.

“I worked a lot of baseball tryouts, camps, and clinics in New Delhi,” Larkin said. “I didn’t see many baseball-specific skills there, but I noticed that there was a lot of athleticism. I said to myself that if I ever got a chance to come back to this region and do something, I’d do it.”

Larkin said he went to Shaikh, whom he had known from some previous promotional projects, and Dubai was eventually chosen as a base of operations “because it’s more centrally located.”

More investors joined over time. Shaikh, Larkin and fellow Hall-of-Famers Mariano Rivera and Adrian Beltre are co-founders and sit on the board of directors along with Chirinos. The former players listed as co-owners also include Albert Pujols, Elvis Andrus, Felix Hernandez, Nick Swisher, Ryan Howard, Bartolo Colon, Hanley Ramirez, Matt Barnes, Shane Victorino, Luis Severino, Jair Jurrjens, Andrelton Simmons, Didi Gregorius, Starling Marte, Ronald Acuna Jr., and Robinson Cano.

As for progress, Shaikh points to accomplishments such as the events held in 2023, 2024, and early 2025; partnering with media outlets such as TBS in Japan, PTV, the national broadcaster in Pakistan, and Zee Entertainment Enterprises in India, both of which will broadcast all this season’s games live; signing up sponsors, including some from the U.S. and Japan; and getting the ballpark built.

The league said that three million viewers watched the international broadcast of the February 2025 series between the Wolves and Falcons and that 17 linear and digital broadcast partners carried the games, with viewership in more than 100 countries.

Appearing on the broadcast of a recent game, Shaikh said that the broadcasts of the opening game attracted approximately seven million viewers. “That’s an MLB All-Star Game-level [of viewership],” he said, “and it’s going to continue adding up.”

Another data point is views of the games streamed over YouTube. The 11 games through December 2 attracted approximately 163,000 views, with per-game views ranging from a low of 7,200 to a high of 24,000.

The ballpark is a story in itself. The original plan had been to play on a modified cricket pitch, but scheduling became an issue, as other events sometimes had priority and bumped baseball to other dates.

“We were the red-headed stepchild,” Shaikh said wryly. “We realized that we couldn’t have a season without having our own stadium.”

So he and his team built Baseball United Ballpark next to a soccer/rugby stadium and a cricket ground – in just 38 days.

“A year ago, this was all dust and dirt,” Shaikh said proudly with a sweep of his arm. “Now, it’s our Field of Dreams here in the desert.”

Its dimensions are identical to those of Yankee Stadium, and it has top-quality lighting with seating for approximately 3,000 fans. If it becomes necessary, the current stands can be expanded higher, and there is room down the lines to add more sections. The stands, as well as the food and drink setups, can be stored when not in use.

Except for the mound, the field is covered with artificial turf, the same as used by the NPB’s Yokohama DeNA BayStars. Carlos Mirabal, Baseball United’s director of baseball operations, did much of the work on this, leveraging contacts he made in Japan during the six seasons he pitched for NPB’s Nippon-Ham Fighters.

“We have to wash the turf to keep the dust off, but we’ll use a lot less water than if we had natural grass,” Mirabal explained. “The area around the mound is a combination of mud from Pakistan and the U.S. Most of it is Pakistan mud, but the area around the rubber and where the pitchers land is American mud because it’s softer.”

Karim Ayubi, an outfielder and Curacao native who has played in the Boston Red Sox organization since 2021, said, “This is a very impressive setup. It surprised me. The turf is good because it’s soft enough and doesn’t get as hot during the days as some turfs do.”

So, going forward . . .

“We want to make sure everyone gets playing time and experiences this journey,” former major league shortstop Jay Bell, who manages the Karachi team, said. “Ultimately, we’re here to represent baseball and help it expand – that’s more important than anything.”

Larkin said, “We want to be a very competitive league; that’s the main thing. Regardless of whether the level of play is rookie league, Class A, AA or whatever. We want our players to get exposure and have chances to play at higher levels. Like the two kids from the Philippines. There is no pro ball there, so maybe playing here will give them a shot somewhere else. Or [Pavin] Parks – maybe he turns out to be a Kyle Schwarber type of guy.”

Jacob Teter, an outfielder/first baseman formerly in the Baltimore Orioles and Houston Astros organizations, looked at this as being an opportunity, as well. “It’s really great to see them bring baseball to a place that doesn’t have it and give guys like me a chance to play and show what we can do. I’ve never been to this part of the world, but I get to come here and play baseball. That’s pretty cool.”

Lou Helmig, a first baseman/outfielder and German national who spent time in the Philadelphia Phillies system and last year was in the U.S. independent leagues, said, “I love this. It’s a new opportunity to make things happen.”

As for next season, Shaikh said “the plan is to have two additional teams and for each team to play 15 games. If we can get another venue, we might lengthen the season to two or two-and-a-half months. The dream scenario is to play during most of the November – February time frame and in multiple locations, but there is a lot to figure out with logistics and politics.”

In March 2024, Baseball United announced a partnership with the Saudi Baseball and Softball Federation that gives the league an unlimited term to host games and tournaments in Saudi Arabia and includes rights to new Baseball United franchises that will represent Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam. But there is much to work out before that happens.

“A limiting factor there is getting partners to help build ballparks,” Shaikh said. “The Saudi sports scene is experiencing massive transformation now in a lot of areas – the 2034 World Cup will be there – and pretty much all the venues are under construction or on lockdown, so we’ve been slower about moving into Saudi.”

For the moment, the primary goal is to put the existing operations on solid footing.

“We’ve come further in three years than anyone expected,” Shaikh said. “The challenge now is to build momentum over the course of this season. Our goal is sustainability, and these next two years are really important.”

NOTES: Miedrich said Baseball United has development programs in India and Pakistan and that the one in Pakistan is near the city of Peshawar, in territory heavily influenced by the Pakistani Taliban. Taliban members sometimes watch baseball training sessions while carrying weapons and wearing bandoliers. Because of tribal custom, the players must wear long pants during workouts, regardless of the temperature . . . With the ballpark’s field almost entirely covered with artificial turf, there is no dirt around the bases or in the batters’ boxes. It was amusing to see hitters automatically start to smooth out the dirt as they approached the plate – only to realize that there was none . . . A dance team performed between innings. While these are almost always comprised entirely of women, there were two men on this eight-person team, and a number of fans remarked on it . . . Of the four umpires, two were from the Czech Republic (Zdenek Zidek and Frantisek Pribyl) and two from Mexico (Jair Fernandez and Humberto Saiz). Zidek has experience umpiring in the U.S. affiliated minor leagues . . . There is no place at the ballpark to store a regular (metal) batting cage – colloquially called a “turtle” – so Baseball United uses an inflatable one.

END TEXT

Unless otherwise noted:

- All quotes from Kash Shaikh are from a Zoom interview that took place September 9, 2025, and from in-person interviews September 14-16, 2025.

- All quotes from Barry Larkin, John Miedrich, Mariano Duncan, Jay Bell, Dennis Cook, Chiharu Yanamura, Lou Helmig, and Karim Ayubi are from in-person interviews September 14-16, 2025.

- Quotes from Antonio Barranca are from a telephone interview September 15, 2025.

- Quotes from Jacob Teter are from a telephone interview September 16, 2025.

In addition, the author consulted baseballreference.com and baseballunited.com.

[i] Go to the top of the eighth inning – starting 2:35 into the broadcast: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_QAPf9g7Z-E&t=9747s.