by Robert Garratt

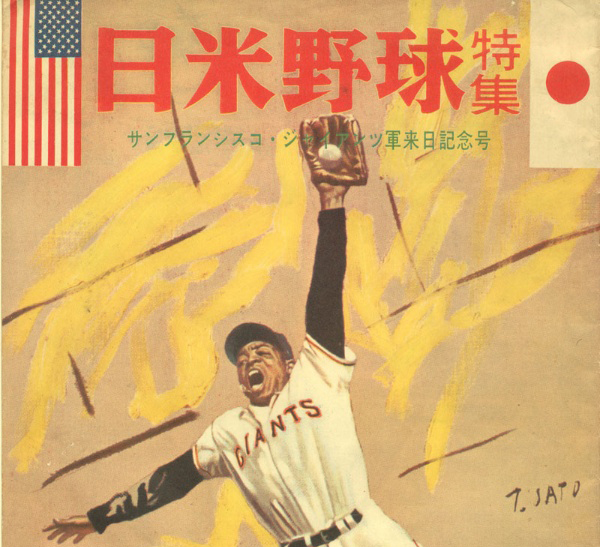

Every Monday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Rob Garratt tells us about Willie Mays and the San Francisco Giants 1960 visit to Japan.

The San Francisco Giants enjoyed a banner year in 1960. After almost five years of planning by the city’s mayor and Board of Supervisors and two years of problem-plagued construction, the Giants’ new ballpark, Candlestick Park, opened in time for the 1960 season. It was a dream come true for Giants owner Horace Stoneham and it justified his move from New York at the end of the 1957 season. The Giants, with a new identity as a West Coast team, now had a permanent location in a new ballpark. The team drew well in its first year at Candlestick, and Stoneham was pleased. And while the Giants would miss out on the National League pennant in 1960, they did manage an exciting postseason, nonetheless. In October 1960, the San Francisco Giants traveled to Japan on a goodwill tour, carrying on a tradition of the city’s connection with Japanese baseball.

San Francisco baseball was known to the Japanese public first through the energy of Frank “Lefty” O’Doul, a San Francisco native who visited Japan in the 1930s with American baseball teams, fell in love with the country and its people, and saw the potential there for good baseball. O’Doul, who is enshrined in Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame for his contribution to the Japanese game, took his San Francisco Seals Pacific Coast League team to Japan in 1949 (O’Doul was the Seals manager), the first time after World War II that an American team toured Japan. The team’s visit was endorsed by General Douglas MacArthur, the American administrator of Occupied Japan, who felt that the game would lift the spirits of the Japanese people and do wonders for diplomacy between two former foes. The Seals’ visit was a resounding success, with the team greeted by some of the largest crowds that had assembled publicly in Japan since the end of the war. By all accounts it was a successful diplomatic venture with the added bonus that it increased the popularity of the game in Japan.

The Giants’ 1960 tour was the second postwar visit for a San Francisco ballclub and the second for Horace Stoneham as well. Stoneham took his New York Giants to Japan for an exhibition tour in 1953, the first single major-league team to do so. The Giants dominated the 1953 series with Japan, drubbing the Yomiuri Giants 11-1 in the opening game and going on to win nine straight games, finishing the series with 12 victories against one loss and one tie. The Japanese players may have lost on the field, but the Japanese people won their way into Stoneham’s heart. The tour itself made a great impression on the Giants’ boss, who was overwhelmed by the enthusiasm of the Japanese fans, and by the gracious hospitality of the Japanese officials. Treated as an international celebrity, he was moved by the attention and honor paid to the Giants as foreign guests and he was charmed by the country itself – its sights, its food, and its ceremonies and rituals that reflected a deep sense of culture. Stoneham was quoted as recognizing the goodwill gesture of the tour, especially its importance in strengthening the ties between the two countries.

Those 1953 memories were dancing in Stoneham’s head in late 1959 when he received an invitation from Japanese officials for the Giants to return to Japan in the fall of 1960. The proposal was backed by Matsutaro Shoriki, owner of the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of the leading newspaper conglomerates in Japan, and brokered by Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, a Nisei Japanese American who was helping develop Japanese baseball in the 1950s. Stoneham was so enthusiastic about the invitation that he sent Lefty O’Doul to Japan in the winter of 1959-60 to work with Harada and Shoriki to firm up the plans; O’Doul had been working for the Giants as a consultant since their arrival in San Francisco and Stoneham wanted to take full advantage of O’Doul’s ties with Japanese baseball. The initial discussions went well and by the summer of 1960, Shoriki and Harada presented the Giants with a formal plan for a tour of Japan.

The proposed invitation called for the Giants to play a 16-game exhibition schedule in 10 Japanese cities, under Japanese rules and officiated by Japanese umpires, with participation by San Francisco’s “star players.” Shoriki was careful to insist on Giants star power, knowing that the likes of Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Orlando Cepeda would appeal to Japanese fans eager to see great hitting. Stoneham was more than happy to accept and returned the signed agreement in late August 1960. Twenty-two players agreed to travel to Japan, including Mays, McCovey, Cepeda, and a young Juan Marichal, all of them future Hall of Famers. Most of the Giants starters joined the tour as well, among them Felipe Alou, Jim Davenport, and pitchers Jack Sanford and Sam Jones. Included were club officials, headed by Stoneham and his wife, Valleda, acting manager Tom Sheehan, club secretary Eddie Brannick, team publicist Garry Schumacher, and O’Doul.

The organizing Japanese committee pulled out all the stops. The schedule of events upon arrival was nothing short of breathtaking, with almost no hour unaccounted for in the daily routines. Everything was meticulously planned from a television press conference at the airport to a celebrity parade from the airport to the city. Crowds lined the 10-mile parade route and packed the rain-soaked streets in downtown Tokyo as the Giants made their way to the hotel. That evening a welcoming dinner reception was held at the Imperial Hotel and Stoneham read a message from San Francisco Mayor George Christopher, a special greeting to “[our] ‘sister city,’ expressing best wishes to the Japanese people on the 100th anniversary of US-Japan diplomatic relations.” On the second day more ceremonial activities took place as the Giants toured Yomiuri’s headquarters, visited the Nihon Television Studios, where the players were interviewed and introduced to Japan’s national TV audience, practiced for 1½ hours at Korakuen Stadium, and attended a reception in their honor at the US Embassy, hosted by Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II, the nephew of General MacArthur. Japanese planners had thought of every probability, working in “alternatives” for events and sightseeing, in case of changes due to bad weather. In what must have seemed a whirlwind pace of parades, receptions, and ceremonial lunches and dinners, the Giants, with very little time for themselves, might have thought that a game of baseball was almost anticlimactic.

On the third day, the time finally came for the Giants to face the Yomiuri Giants in the inaugural game of the tour. But the visiting players would wait again as the game provided the Japanese with yet another opportunity for pregame pageantry, described by one source as part parade, part theater spectacle, as “shapely Japanese models and the Tokyo police band led the Japanese and American Giants around Korakuen Stadium as fireworks exploded, and balloons and pigeons soared skyward.” Once the teams had finished the procession and the air had cleared, Ambassador MacArthur read a greeting from President Dwight Eisenhower that recalled the long history of exchanges between Japanese and American baseball players, noting the important role of the national pastime in both countries. The president’s message stressed the importance of this year’s exhibition series as a promotion of “the spirit of international understanding and co-operation essential to the peace of the world.” Then Matsutaro Shoriki threw out the traditional first ball and the game officially began, at last.

Initially things did not fare well for the visitors, who were perhaps weary from international travel and overwhelmed by welcoming ceremonies. In the first two games of the scheduled 16-game tour, the Japanese beat San Francisco, much to the surprise and chagrin of some of the local sportswriters, who expressed a tinge of disappointment over the Japanese success. Writing for the Japan Times, Katsundo Mizuno labeled the Giants’ start as the “worst of any major league outfit” that ever visited Japan, and he wondered what was wrong with them. The headlines in the local coverage of the opening game reflected a mixture of shock with a dash of hyperbole: “Tokyo’s Yomiuri Giants Bomb San Francisco, 1-0” although the Japanese managed only two hits against Giants pitching.

The first game was the only one in which San Francisco faced players from a single team. For the rest of the exhibition tour, the Giants played squads of all-stars drawn from the two Nippon Professional Baseball leagues. The Giants lost the second game, but managed a win in Game 3, prompting the Japanese journalists to collect their breath, astonished by the Americans’ poor start. “By squeaking past the Japan All-Stars 1-0 at Tokyo’s Korakuen stadium yesterday, the Giants have averted unheard of catastrophe for major league baseball. No visiting U.S. big league team has ever lost three games in a row in Japan.” Hisanori Karita, a veteran Japanese baseball commentator, was quoted as demanding more “major-style action” from the visitors.

When questioned by the Japanese press about their slow start, Giants players and team officials responded politely and diplomatically, although privately they must have wondered what the fuss was about, given that they were adjusting to international travel, a frenetic welcome schedule, and a foreign cultural environment. Interim Giants manager Tom Sheehan tried some American tongue-in-cheek humor, “I understand we’ve set a new record for major leaguers by losing two games in a row. We may lose all the remaining games, too, you know.” “We’ll play better tomorrow,” he added.

The folksy Sheehan proved a truthful prognosticator. Games 4 and 5 were on the road, in Sapporo and Sendai, and the San Franciscans won them both, with plenty of offense including four home runs, three of them by Willie McCovey. The Giants then returned to Tokyo for two more games at Korakuen Stadium, which they split with the host team, giving them a 4-3 record for the series as they prepared to play the rest of the tour “on the road.” One highlight for the American squad was the attendance of Japanese royalty in Game 6 at Korakuen. Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko, guests of Matsutaro Shoriki, watched the Japanese all-stars erupt for 10 runs – the most they would score in any game of the tour – and beat the Giants, 10-7, before 32,000 fans. The crown prince and princess saw Willie Mays homer in the game, and then watched All-Star Isao Harimoto answer with a two-run blast of his own.

For the remainder of the exhibition tour, the Giants played outside of Tokyo, on a swing throughout southern Japan taking them to seven cities: Toyama; a three-game series in Osaka; Fukuoka; Shimonoseki; Hiroshima; Nagoya; and finishing in Shizuoka. It was on this road trip that the Giants found their mojo, winning seven straight games. But it was the manner in which they won that was impressive. Unlike the games played in Tokyo, which were usually low-scoring and tight, most of the road games were one-sided, with the Giants’ bats coming alive, much to the delight of the Japanese fans, who expected to see home run fireworks from the likes of Mays, McCovey, and Cepeda.

After an unusual game in Toyama in which the Giants banged out three home runs in the first inning to take a seven-run lead, only to see the All-Stars claw their way back, highlighted by a three-run homer by Kenjiro Tamiya off Mike McCormick – the game ended in 10 innings in a 7-7 tie – it was on to Osaka. The Giants found this stop to their liking, sweeping the three-game series in front of enthusiastic Osaka fans (the three games drew 90,000). During the Osaka series, they also enjoyed a day off touring the historic city of Kyoto.

Then it was on to Fukuoka, where the Giants won decisively, 8-4, and then to Shimonoseki, where they beat the all-star team, 11-5, in a demonstration of offensive fire, hitting four home runs. In an example of the goodwill that underscored and permeated the entire baseball tour, there was a somber and emotional moment when the Giants arrived in Hiroshima. Prior to the game, which the Giants won, 4-1, Stoneham led the players and team officials to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where both Stoneham and Sheehan placed bouquets of flowers by the Memorial Cenotaph in a solemn ceremony honoring the memory of those Hiroshima citizens who died in the final days of World War II. After Hiroshima, the Giants traveled to Nagoya and put up big numbers once again in a 14-2 win. The last game of the tour was played at Shizuoka’s Kusanagi Stadium on November 13, won by the Japanese All-Stars, 3-2. The Giants totals for the series were 11 wins, 4 losses and 1 tie. After the game, the Giants boarded a train to Tokyo for three days of sightseeing before they flew home on Friday, November 18.

*****

Despite their slow start, the Giants finished their exhibition goodwill tour of Japan with a flurry and put up impressive numbers for the series, hitting 31 homers over 16 games, much to the delight of the Japanese fans; McCovey hit eight home runs, Mays seven, and Cepeda five. Mays hit .393 for the tour and was named by the all-star and Giants managers as the series’ Most Valuable Player. Giants pitching was strong as well, with an overall 2.41 ERA and 92 strikeouts in 142 innings. Sam Jones had a 3-0 record with an amazing 0.82 ERA; Juan Marichal posted a 1.55 ERA with a 2-0 record and a complete game; Mike McCormick had 22 strikeouts in 23 ⅔ innings. In a memorable and significant moment for Japanese fans, Jones displayed his own version of goodwill when he went over to first base after hitting a batter and apologized to the hitter. There were other friendly exchanges between the Giants players and the all-stars throughout the tour, some of which involved discussions of techniques for hitting and pitching. Overall, the relations between the two teams were positive and gracious, with a healthy sense of mutual respect. The Japanese fans were also captivated by the tour and turned out in all the cities to welcome the Giants and attend the games. The fans’ enthusiasm was evident in the exhibition tour’s great success at the turnstiles. The Giants drew 441,000 for the 16 games, according to the Japan Baseball Commission and the Yomiuri Shimbun.

*****

For all the goodwill that came of the Giants’ visit, the tour was not without its controversy, however. Buoyed by the games and the enthusiastic Japanese response – both the total attendance and the ticker-tape parades in various cities that drew huge crowds – and heady about the future of cooperation between the United States and Japan, Ambassador MacArthur spoke at a farewell reception at the US Embassy of more baseball competition between the two countries. MacArthur was specific in his proposal; he envisioned a future world series between the American champion and the Japanese champion and even had a date in mind. He thought an initial exhibition series could be played in 1964, in concert with the Tokyo Olympic Games, which could lead to a more established series a few years later.

His idea was immediately supported by Nobori Inouye, the commissioner of Japanese baseball. Both Lefty O’Doul and Cappy Harada also favored the idea and thought that with reasonable planning an international world series could take place perhaps in five or six years. Both men felt that Japanese baseball was improving rapidly and would offer good competition. So did Stoneham. In a press conference upon his return to San Francisco, the Giants boss remarked that he was “amazed” at the improvement of the Japanese players in the seven years since he first visited Japan. Moreover, Stoneham wanted a continued connection with Japanese baseball.

But when Harada, who was working as a consultant to the Giants, brought the idea to Commissioner Ford Frick in New York, it was dead-on-arrival. Perhaps it was an idea that was too embryonic, requiring planning, research, and co-operation between organizations. Possibly Frick accepted the prevailing view of Japanese baseball as inferior to the American game. Or it might have been the process by which the idea took flight that Frick objected to, coming out of the blue from an American ambassador in Japan. What was certain, however, was that Frick wanted to assert his authority about such matters. He fired off an official statement indicating that no decision can be made about any international baseball series without input from the commissioner’s office, and suggested that he had no immediate plans to entertain such a proposal.

Another controversy emerged during the tour involving the Giants’ interest in Japanese players. Upon Stoneham’s arrival in Japan, in an uncharacteristic slip of the tongue – Stoneham usually was tight-lipped about personnel matters, especially when it came to player acquisitions – the Giants’ owner commented that there were “several Japanese players we have heard about and are anxious to see.” Explaining that he would like to reach some formal agreement with a few Japanese clubs, he hoped to invite some players to the Giants’ spring training. These were just casual remarks folded into his words of appreciation of the Japanese invitation and nothing much was spoken about any plans or arrangements for the first 10 days of the tour. By the end of the second week, however, word had leaked to some in the press that Stoneham was interested in signing some Japanese players, or at least having them affiliate in some fashion with his organization, including a spring-training visit.

While the newspapers were speculating, Stoneham was working quietly behind the scenes. When the Giants arrived in Osaka on November 3 for the three-game series, Stoneham extended an invitation to the Nankai Hawks, to have pitcher Tadashi Sugiura attend their 1961 spring training in Arizona. The Japanese responded almost immediately to the offer. Makoto Tachibana, the president of the Nankai Hawks, issued a statement to the local press rejecting Stoneham’s invitation and made it clear he was suspicious of the Giants’ motives.

“I feel it isn’t only a case of having [Sugiura] attend the camp, but an underlying intention to hire him,” Tachibana said. “Even if this isn’t true, it can be considered that they may want to learn something from him, to – I hate to say it – steal his techniques.” Tachibana’s paranoia tended somewhat to the bizarre – “there is a possibility they want to use Sugiura for experiments” – but the Nankai owner’s root cause for worry was evident in his closing remarks to the press. He feared that Sugiura would be “separated from his team,” that is, playing for the Giants, “and we cannot permit a man as valuable to Japanese baseball to be used to his disadvantage.” The concern that Japanese baseball might lose some of its best players to American clubs was clear. There was also an invitation extended to a position player, Takeshi Kuwata, a third baseman for the Taiyo Whales, but that, too, came to nothing. The invitations and their subsequent refusals were minor incidents in the larger story of the tour, the games, the associations between players and the Japanese fans’ excitement over the competition, but they provided an interesting subplot to the 1960 Giants’ visit.

Once home from Japan, Stoneham more or less confirmed Tachibana’s suspicions. In remarks to a local sportswriter at a post-tour press conference, the Giants boss praised the Japanese players, taking care to emphasize the improvements in the quality of play, the skill, and the athleticism of many Japanese players since his 1953 visit with his New York Giants team. He implied that a few of the Japanese players, chiefly pitchers, might be able to have good results immediately in the major leagues, something that Tom Sheehan had noticed on the tour. That Stoneham saw the potential of Japanese players is not surprising; he had become a keen observer of major-league talent over the years. What is surprising is how prescient his notions were in the fall of 1960. The thinking behind those public remarks would take shape quickly, much to the surprise of both the major leagues and Nippon Professional Baseball. Just three years later, Stoneham’s musings on Japanese players would materialize with a radical move that would change baseball history.

In the fall of 1963, Cappy Harada, working for Stoneham as a scout and on the payroll with the Nankai Hawks as a consultant, came up with a proposal for cooperation between the two clubs. With Stoneham’s blessing, Harada arranged for three Hawks players – third baseman Tatsuhiko Tanaka, catcher Hiroshi Takahashi, and pitcher Masanori Murakami – to come to the United States for 1964 spring training and a chance to develop within the Giants’ minor-league system. According to the agreement, the Japanese players would participate in general spring training and then be assigned to minor-league teams for the rest of the season, Murakami at single A, and Tanaka and Takahashi at lower levels. Once the minor-league season was finished, the Giants sent the position players home to Japan, but kept Murakami, who had progressed so well in Fresno that he was called up to the big club in September. On Tuesday evening, September 1, 1964, in Shea Stadium, New York, Murakami made history as a baseball pioneer, pitching one inning of scoreless relief, the first Japanese national to play in the majors. He would pitch through the month of September and would return to the Giants for the 1965 season.

Horace Stoneham has many achievements on his résumé as a baseball owner. After Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Stoneham was soon to follow with the signing of African American players. He led the way in breaking a second barrier in the signing of Latino players. Along with Bill Veeck, he was responsible for founding the Cactus League in 1948. With his signing of Murakami, he broke another barrier in baseball, making the game global. It is tempting to think that this last achievement germinated in the stands at Japanese ballparks in 1960, as the Giants boss watched the Japanese players, especially the pitchers. He was certainly impressed enough with the players’ abilities to extend an invitation for two of them to come to spring training, even though the gesture did not bear fruit. Nonetheless, he sensed the latent talent in Japanese baseball. And perhaps on that 1960 tour, he saw the immediate future: a Japanese national wearing the uniform of the San Francisco Giants and playing in the major leagues.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website