by C. Paul Rogers III

Every Monday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week C. Paul Rogers III tells us about the 1953 Major League All-Stars visit to Japan.

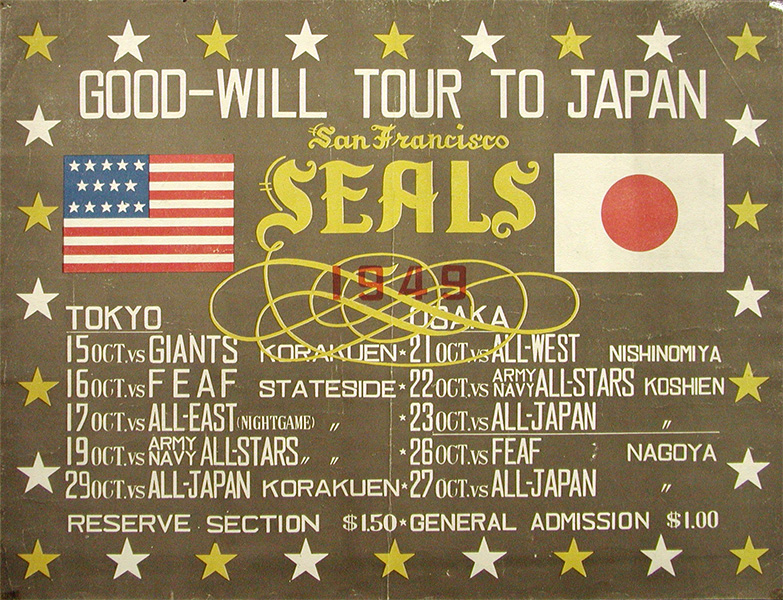

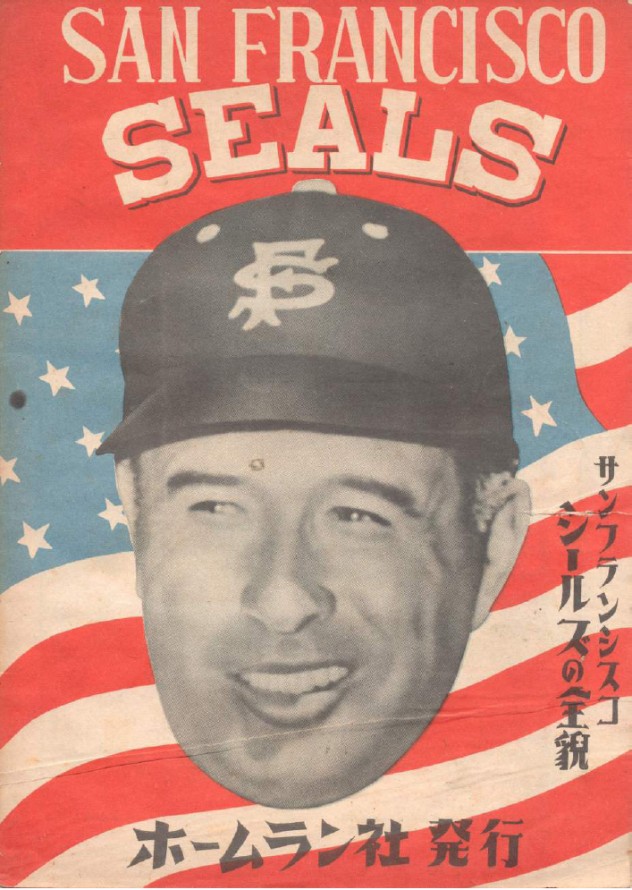

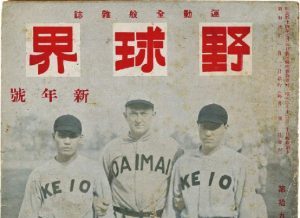

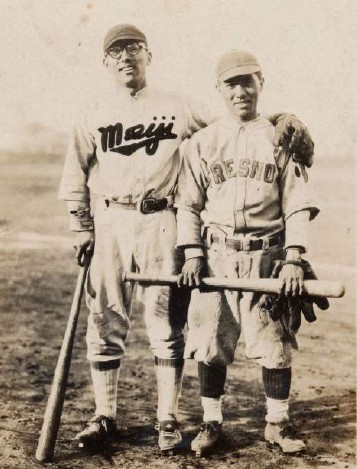

Eddie Lopat was a fine, soft-tossing southpaw during a 12-year baseball career with the Chicago White Sox and most famously the New York Yankees. Called the Junkman because of his assortment of off-speed pitches, Lopat was also something of a baseball entrepreneur. He not only ran a winter baseball school in Florida, but, after barnstorming in Japan with Lefty O’Doul’s All-Stars following the 1951 major-league season, was very receptive to Frank Scott’s plan to put together a star-studded assemblage of major leaguers to again tour Japan after the 1953 season. Scott, a former traveling secretary of the Yankees who had since become a promoter, proposed calling the team the Eddie Lopat All-Stars. By 1953, after O’Doul’s 1949 breakthrough overseas trip to Japan with his San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, postseason tours to the Land of the Rising Sun had become more common. In fact, in 1953 the New York Giants also barnstormed in Japan at the same time as did Lopat’s team. For the Lopat tour, Scott secured the Mainichi Newspapers, owners of the Mainichi Orions of Japan’s Pacific League, as the official tour sponsor.

Lopat and Scott spent much of the 1953 regular season recruiting players for the tour, including a somewhat reluctant Yogi Berra. Unbeknownst to Yogi, he was already a legend among Japanese baseball fans. At the All-Star Game in Cincinnati, a Japanese sportswriter who was helping Lopat and Scott with their recruiting was aware of Berra’s reputation as a chowhound and told Yogi about the exotic foods he would be able to consume in Japan. Yogi was skeptical, however, and wondered if bread was available in Japan. When the writer and Lopat both assured Yogi that Japan did indeed have bread, he signed on for the tour.

Under the prevailing major-league rules, barnstorming “all-star teams” were limited to three players from any one team. With that constraint, a stellar lineup of major leaguers signed on for the tour including, in addition to Berra, future Hall of Famers Mickey Mantle, Robin Roberts, Eddie Mathews, Bob Lemon, Nellie Fox, and Enos Slaughter. All-Star-caliber players like Eddie Robinson, Curt Simmons, Mike Garcia, Harvey Kuenn (the 1953 American League Rookie of the Year), Jackie Jensen, and Hank Sauer committed as well, as did Gus Niarhos, who was added to serve as a second catcher behind Berra. Whether a slight exaggeration or not, they were billed as “the greatest array of major league stars ever to visit Japan.”

Lopat and his Yankees teammates Mantle and Berra were fresh off a tense six-game World Series win over the Brooklyn Dodgers in which all had played pivotal roles. Lopat had won Game Two thanks to a two-run eighth-inning homer by Mantle, while Berra had batted .429 for the Series. A casualty to the tour because of the long season and World Series, however, was the 21-year-old Mantle, who, after battling injuries to both knees during the year, needed surgery and was a late scratch. Lopat quickly added Yankees teammate Billy Martin, who had hit .500 with 12 hits and eight runs batted in in the Series to win the Baseball Writers’ MVP Award.

The Lopat All-Stars were to first play four exhibition games in Colorado and began gathering at the famous Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs on October 6. Baseball had a no-fraternizing rule then and many of the players looked forward to getting to know ballplayers from other teams and from the other league. The Phillies’ Robin Roberts, who was known for his great control on the mound, remembered spotting fellow hurler Bob Lemon of the Cleveland Indians in the bar at the Broadmoor and going over to introduce himself. Lemon asked Roberts what he wanted to drink and Roberts said, “I’ll have a 7-Up.”

Lemon didn’t say anything but pulled out a pack of cigarettes and offered Roberts one. Roberts said, “No, thanks, I don’t smoke.”

Lemon chuckled and said, “No wonder you don’t walk anyone.”

The Lopat team’s opposition in Colorado was a squad of major leaguers put together by White Sox manager Paul Richards and highlighted by pitchers Billy Pierce and Mel Parnell, infielders Pete Runnels and Randy Jackson, and outfielders Dave Philley and Dale Mitchell.

The big-league sluggers quickly took to the rarefied Colorado air as the teams combined for nine home runs in the first contest, a 13-8 victory for the Lopat All-Stars over the Richards group on October 8 in Pueblo. The 21-year-old Mathews, coming off a gargantuan 47-homer, 135-RBI season with the Braves, slugged two circuit shots (including one that traveled 500 feet), as did the Cubs’ 36-year-old Hank Sauer, the Cardinals’ 37-year-old Enos Slaughter, and, for the Richards team, Detroit catcher Matt Batts. Two days later, the Lopats blasted the Richards team 18-7 in Colorado Springs before the four-game series shifted to Bears Stadium in Denver for the final two contests. The results were the same, however, as the Lopat team won in the Mile-High City 8-4 and 14-8, the latter before a record crowd of 13,852, as fourtime American League All-Star Eddie Robinson of the Philadelphia A’s and Mathews both homered off Billy Pierce and drove in four runs apiece.

Mathews went 7-for-8 in the two Denver contests and posted Little League-like numbers for the whole Colorado series, driving in 17 runs in the four games, while the veteran Slaughter had 12 hits, including two homers, two triples, and three doubles.

The Lopat All-Stars then flew to Honolulu for more exhibition games after a brief stopover in San Francisco. On October 12 and 13 they played a pair of games in Honolulu against a local team called the Rural Red Sox and it did not take long for disaster to strike. In the first inning of the first game before a jammed-in crowd of 10,500, Mike Garcia of the Indians was struck in the ankle by a line drive after delivering a pitch. Garcia, who had won 20, 22, and 18 games the previous three seasons, was unable to push off from the mound after the injury and had to leave the game. Although Garcia stayed with the team for most of the tour, he was able to pitch only sparingly in Japan.

Despite the loss of Garcia, the major leaguers clobbered the locals 10-2 and 15-0. After the second game, first baseman Robinson, who had homered in the rout, was stricken with a kidney-stone attack and was briefly hospitalized. He quickly recovered and resumed the tour for the All-Stars, who had brought along only 11 position players.

On October 14 the Lopat squad flew to Kauai, where they pounded out 22 hits and defeated the Kauai All-Stars, 12-3, on a makeshift diamond fashioned from a football field. World Series MVP Martin was honored before the game and given a number of gifts, including an aloha shirt and a calabash bowl. He celebrated by smashing a long home run in his first time at bat and later adding a double and a single. The homer sailed through goalposts situated beyond left field, leading Robin Roberts to quip that it should have counted for three runs.

The big leaguers next flew to Hilo on the Big Island, where on October 17, 5,000 saw them defeat a local all-star-team, 8-3, in a game benefiting the local Little League. But much more serious opposition awaited them back in Honolulu in the form of a three- game series against the Roy Campanella All-Stars, a team of African American major leaguers headed by Campanella, the reigning National League MVP, and including stellar players like Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Billy Bruton, Joe Black, Junior Gilliam, George Crowe, Harry “Suitcase” Simpson, Bob Boyd, Dave Hoskins, Connie Johnson, and Jim Pendleton.

The Lopats won the first game, 7-1, on the afternoon of October 18 over an obviously weary Campanella team that had flown in from Atlanta the previous day, with a plane change in Los Angeles. Jackie Jensen, then with the Washington Senators, was the hitting star with two home runs, while the Phillies’ Curt Simmons allowed only a single run in eight innings of mound work. By the next night, Campy’s squad was in much better shape and defeated the Lopat team 4-3 in 10 innings behind Joe Black.

Roberts pitched the first nine innings for the Lopats with Yogi Berra behind the plate. In one at-bat, Campanella hit a towering foul ball behind the plate. Campy actually knocked the glove off Yogi’s hand on the follow-through of his swing. Berra looked down at his glove on the ground and then went back and caught the foul ball barehanded.

Roberts picked up Yogi’s glove and handed it to him, asking him if he was okay. Yogi said, “That friggin’ ball hurt like hell.”

Over the years Roberts wondered if he had somehow made that story up, since he never again saw a bat knock the glove off a catcher’s hand. Over 30 years later, he saw Berra at an Old-Timers game in Wrigley Field in Chicago and asked him about it. Yogi said, “That friggin’ ball hurt like hell,” the exact thing he had said in 1953.

On October 20 Campanella’s squad won the rubber game, 7-1, behind the three-hit pitching of Don Newcombe. Nellie Fox displayed rare power by homering for the Lopats’ only run, while George Crowe hit two homers and Junior Gilliam one for the Campanellas.

The Lopat team stayed at the famous Royal Hawaiian Hotel on Waikiki Beach and had such a great time in Hawaii that many didn’t want to leave. Many of the players had brought their wives but some like Eddie Mathews, Billy Martin, and Eddie Robinson were single and so enjoyed the Honolulu nightlife. Not surprisingly given his before and after history, Martin got into a dispute with a guard at a performance of hula dancers attended by the entire team and sucker-punched him. Fortunately for Martin, no charges appear to have been brought.

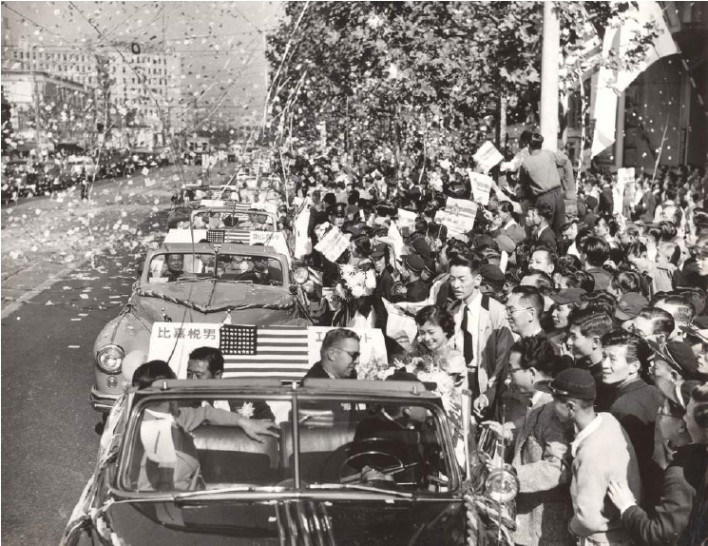

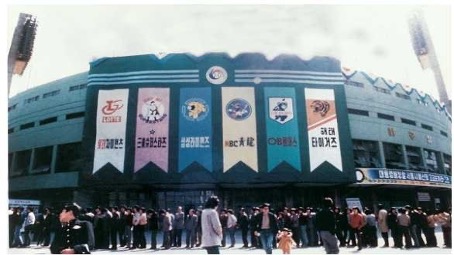

The Lopat squad did have a schedule to keep and flew on a Pan American Stratocruiser to Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, arriving at 1:05 P.M. on October 22. They could scarcely have anticipated the frenzied reception they received. Although the New York Giants had been in the country for a week and had played five games, thousands of Japanese greeted the plane. After being officially greeted by executives from the trip sponsor, Mainichi, and receiving gifts from beautiful young Japanese women, the ballplayers climbed into convertibles, one player per car, to travel to the Nikkatsu Hotel, which would be their headquarters. The trip, which would normally take about 30 minutes, took almost three hours because of the throngs of fans lining the route and pressing against the cars as Japanese mounted and foot police were overwhelmed. Eddie Mathews likened it to the pope in a motorcade without police or security while it reminded Robin Roberts of a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

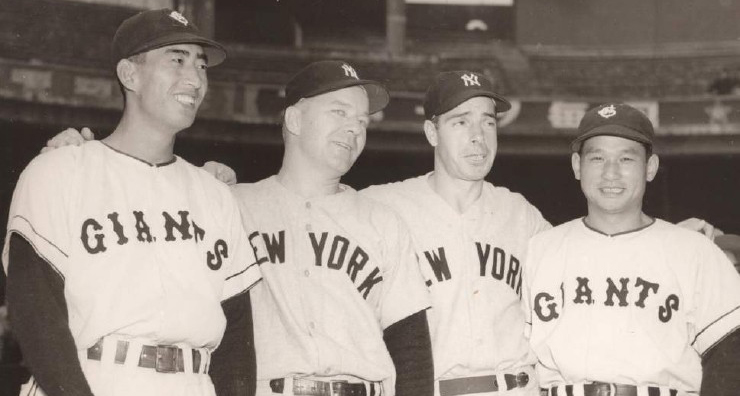

That evening the Americans were guests at a gigantic pep rally in their honor at the Nichigeki Theater, where Hawaiian-born Japanese crooner Katsuhiko Haida introduced each player. American Ambassador John M. Allison also hosted a reception at the US Embassy for both the Lopats and the New York Giants, who had just returned to Tokyo from Sendai.

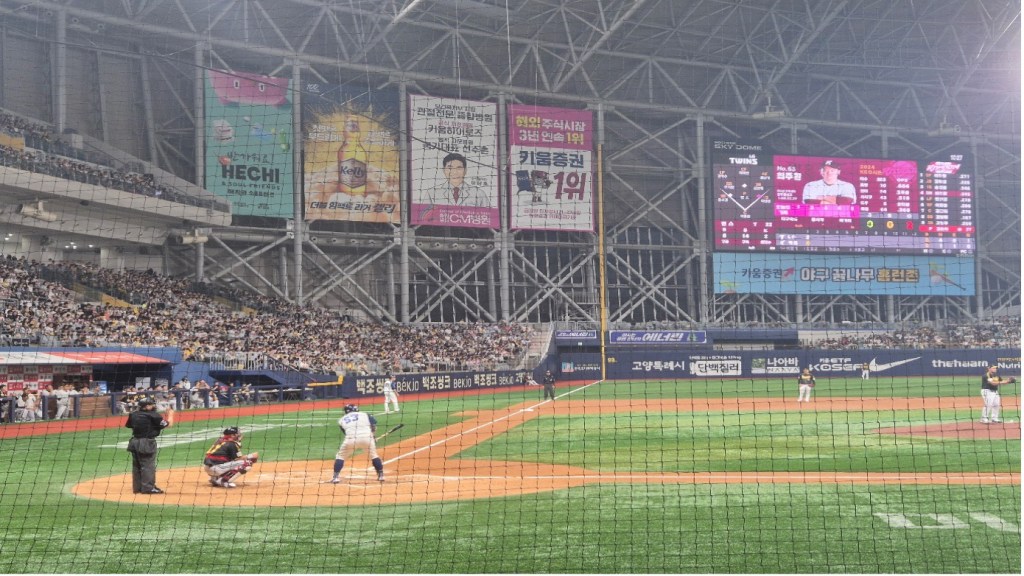

The Lopat squad’s first game was the following afternoon, October 23, against the Mainichi Orions in Korakuen Stadium before 27,000. The Orions, who had finished fifth out of seven teams in Japan’s Pacific League, had the honor of playing the initial game due to its ownership by the Mainichi newspapers. Jackie Jensen won a home-run-hitting contest before the game by smacking six out of the yard, followed by Futoshi Nakanishi of the Nishitetsu Lions with three and then Berra, Mathews, and Hank Sauer with two each. Bobby Brown, stationed in Tokyo as a US Army doctor, was seen visiting in the dugout with his Yankee teammates Lopat, Berra, and Martin before the contest.

The US and Japanese Army bands played after the home-run-hitting contest, followed by helicopters dropping bouquets of flowers to both managers. Another helicopter hovered low over the field and dropped the first ball but stirred up so much dust from the all-dirt infield that the start of the game was delayed.

The game finally began with Curt Simmons on the mound for the Americans against southpaw Atsushi Aramaki. The visitors plated a run in the top of the second on a single by Sauer, a double by Robinson, and an error, but the Orions immediately rallied for three runs in the bottom half on three bunt singles and Kazuhiro Yamauchi’s double. The Orions led 4-1 heading into the top of the ninth but the Lopats staged a thrilling rally to tie the score behind a walk to Mathews, a two-run homer by Sauer, and Robinson’s game-tying circuit clout.

Garcia, who had relieved Simmons in the seventh inning, was still pitching in the 10th but after allowing a single, reaggravated the leg injury suffered in Hawaii. He was forced to leave the game with the count of 1 and 1 against the Orions’ Charlie Hood, who was a minor-league player in the Phillies organization. (Hood was in the military stationed in Japan and had played 25 games for Mainichi during the season.) When Garcia had to depart, Lopat asked for volunteers to pitch. Roberts, sitting in the dugout, said he would and went out to the mound to warm up.

During the game Roberts had told Bob Lemon next to him that he was familiar with Hood from Phillies spring training and that he was a really good low-ball hitter. Then, on his first pitch, Roberts threw Hood a low fastball which he ripped down the right-field line for a game-winning double. Lemon ribbed Roberts for the rest of the trip about his throwing a low fastball to a low-fastball hitter. In one of baseball’s little coincidences, Roberts and Lemon would both be elected to the Hall of Fame on the same day in 1976, 23 years later.

The Lopat squad’s loss in the opener was only the third ever suffered by an American team of major leaguers in a postseason tour of Japan. The All-Stars were certainly embarrassed by losing to a mediocre team and afterward Roberts told the Japanese press, “Look, it’s a goodwill trip and so this was some of our goodwill. You won the first game, but you won’t win anymore.”

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website