by Robert Fitts

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. In this article Robert Fitts discusses the first Japanese American teams to visit Japan.

INTRODUCTION

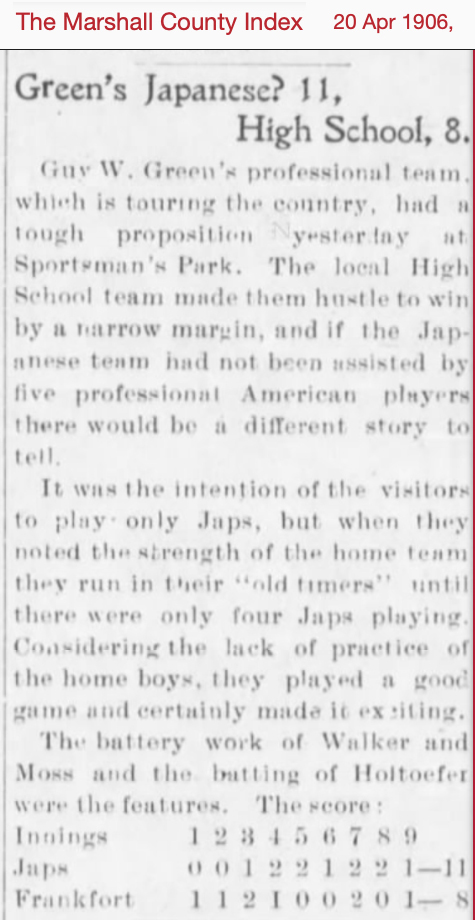

Between 1890 and 1910, over 100,000 Japanese immigrated to the West Coast of the United States. Many settled in the urban centers of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Within a few years, each of these immigrant communities had thriving baseball clubs. The first known Japanese American team was the Fuji Athletic Club, founded in San Francisco around 1903. A second Bay Area team, the Kanagawa Doshi Club, was created the following year. That same year, newsmen at the Rafu Shimpo organized Los Angeles’s first Issei (Japanese immigrant) team. Other clubs followed in the wake of Waseda University’s 1905 baseball tour of the West Coast. Many players learned the game while still in Japan at their high schools or colleges. Others picked up the sport in the United States. The first Japanese professional club was created the following year by Guy Green of Lincoln, Nebraska. His Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, consisting of Japanese immigrants from Los Angeles, barnstormed throughout the Midwest in the spring and summer of 1906.

Seattle’s first Japanese American club, called the Nippon, was also organized in 1906. Shigeru Ozawa, one of the founding players, recalled that the team was not very good at first and was able to play only the second-tier White amateur nines. By 1907 the team had a large local following. In its first appearance in the city’s mainstream newspapers, the Seattle Star noted that “before one of the largest crowds seen at Woodlands park the D.S. Johnstons defeated the Nippons, the fast local Jap team, by a score of 11 to 5.” In May 1908, before a game against the crew of the USS Milwaukee,the Seattle Daily Times reported that the Nippon “have picked up the fine points of the great national game rapidly from playing the amateur teams around here every Sunday.”

Two months later, the Daily Times featured the team when it took on the all-female Merry Widows. Mistakenly referring to the Nippons as “the only Japanese baseball club in America,” the newspaper reported, “when these sons of Nippon went up against the daughters of Columbia, viz., the Merry Widow Baseball Club, it is a safe assumption that the game played at Athletic Park yesterday afternoon was the most unique affair in the annals of the national game.” Over a thousand fans, including many Japanese, watched the Nippons win, 14-8.

Soon after the game with the Merry Widows, second baseman Tokichi “Frank” Fukuda and several other players left the Nippon and created a team called the Mikado. The Mikado soon rivaled the Nippons as the city’s top Japanese team, with the Seattle Star calling them “one of the fastest amateur teams in the city.” In both 1910 and 1911, the Mikado topped the Nippon and Tacoma’s Columbians to win the Northwest Coast’s Nippon Baseball Championship.

As Fukuda’s love for baseball grew, he realized the game’s importance for Seattle’s Japanese. The games brought the immigrants together physically and provided a shared interest to help strengthen community ties. It also acted as a bridge between the city’s Japanese and non-Japanese population, showing a common bond that he hoped would undermine the anti-Japanese bigotry in the city.

In 1909 Fukuda created a youth baseball team called the Cherry—the West Coast’s first Nisei (Japanese born outside of Japan) squad. Under Fukuda’s guidance, the club was more than just a baseball team. Katsuji Nakamura, one of the early members, explained in 1918, “The purpose of this club was to contact American people and understand each other through various activities. We think it is indispensable for us. Because there are still a lot of Japanese people who cannot understand English in spite of the fact that they live in an English-speaking country. That often causes various troubles between Japanese and Americans because of simple misunderstandings. To solve that issue, it has become necessary that we, American-born Japanese who were educated in English, have to lead Japanese people in the right direction in the future. We have been working the last ten years, according to this doctrine.”

As the boys matured, the team became stronger on the diamond and in 1912 the top players joined with Fukuda and his Mikado teammates Katsuji Nakamura, Shuji “John” Ikeda, and Yoshiaki Marumo to form a new team known as the Asahi. Like the Cherry, the Asahi was also a social club designed to create the future leaders of Seattle’s Japanese community, and forge ties with non-Japanese through various activities, including baseball. Once again the new club soon rivaled the Nippon as Seattle’s top Japanese American team.

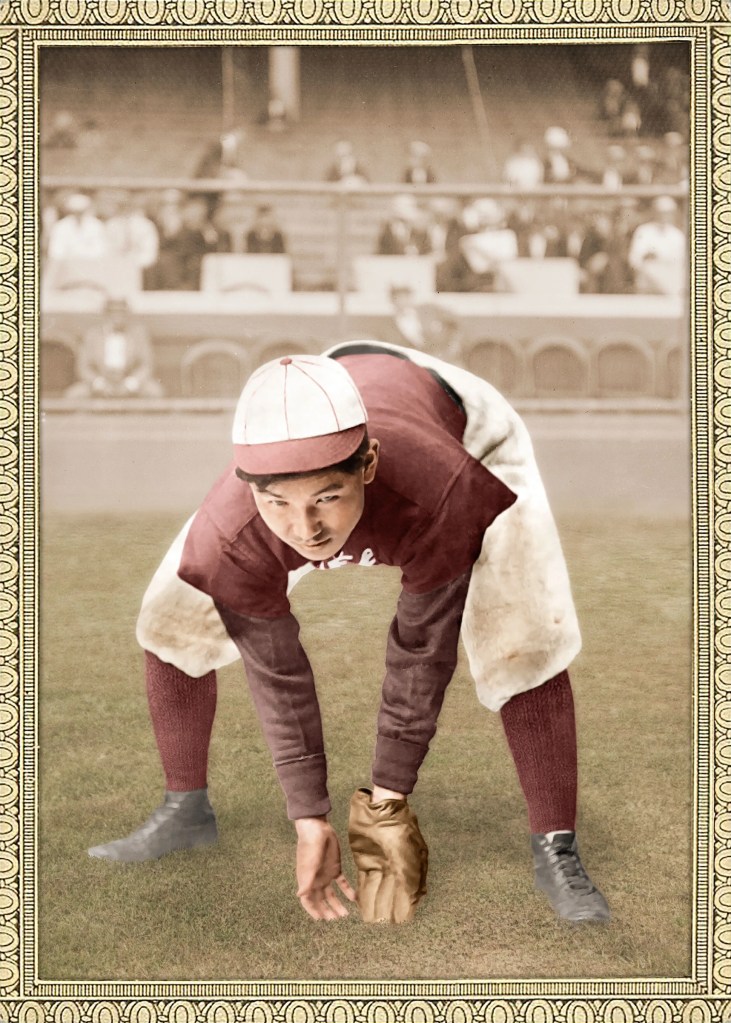

THE NIPPON TOUR

During the winter of 1913-14, Mitomi “Frank” Miyasaka, the captain of the Nippon, announced that he was going to take his team to Japan, thereby becoming the first Japanese American ballclub to tour their homeland. To build the best possible squad, Miyasaka recruited some of the West Coast’s top Issei players. From San Francisco, he recruited second baseman Masashi “Taki” Takimoto. From Los Angeles, Miyasaka brought over 30-year-old Kiichi “Onitei” Suzuki. Suzuki had played for Waseda University’s reserve team before immigrating to California in 1906. A year later, he joined Los Angeles’s Japanese American team, the Nanka. He also founded the Hollywood Sakura in 1908. In 1911 Suzuki joined the professional Japanese Base Ball Association and spent the season barnstorming across the Midwest. Miyasaka’s big coup, however, was Suzuki’s barnstorming teammate Ken Kitsuse. Recognized as the best Issei ballplayer on the West Coast, in 1906 Kitsuse had played shortstop for Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team, the first professional Japanese club on either side of the Pacific. He was the star of the Nanka before playing shortstop for the Japanese Base Ball Association barnstorming team in 1911. Throughout his career, Kitsuse drew accolades for his slick fielding, blinding speed, and heady play.

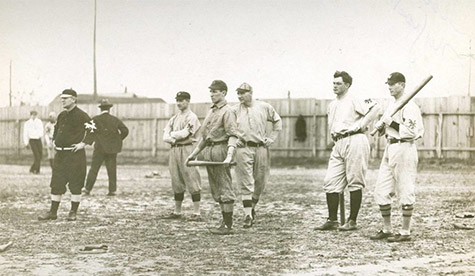

To train the Nippons in the finer points of the game, Miyasaka hired 38-year-old George Engel (a.k.a. Engle) as a manager-coach. Although Engel had never made the majors, he had spent 14 seasons in the minor leagues, mostly in the Western and Northwest Leagues, as a pitcher and utility player. Miyasaka also created a challenging schedule to ready his team for the tour. They began their season with games against the area’s two professional teams from the Northwest League. On Sunday, March 22, they lost, 5-1, to the Tacoma Tigers, led by player-manager and future Hall of Famer Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity. The following Sunday the Seattle Giants, which boasted seven past or future major leaguers on the roster, beat them 5-1. Despite the one-sided loss, the Seattle Daily Times noted, “the Nippons … walked off Dugdale Field yesterday afternoon feeling well satisfied with themselves for they had tackled a professional team and had made a run.”

In April 1914, Keio University returned for its second tour of North America. After dropping two games in Vancouver, British Columbia and a third to the University of Washington, Keio met the Nippons on April 9 at Dugdale Park in what the Seattle Daily Times called “the world’s series for the baseball championship of Japan.” On the mound for Keio was the great Kazuma Sugase, the half-German “Christy Mathewson of Japan,” who had starred during the school’s 1911 tour. The team also included future Japanese Hall of Famers Daisuke Miyake, who would manage the All-Nippon team against Babe Ruth’s All-Americans in 1934, and Hisashi Koshimoto, a Hawaiian-born Nisei who would later manage Keio.

Nippons manager George Engel was in a quandary. His usual ace Sadaye Takano was not available and as Keio would host his team during its coming tour of Japan, he needed the Nippons to prove they could challenge the top Japanese college squad. Engel reached out to William “Chief’ Cadreau, a Native American who had pitched for Spokane and Vancouver in the Northwestern League, one game for the 1910 Chicago White Sox, and would later pitch a season for the African American Chicago Union Giants. Pretending that he was a Japanese named Kato, Cadreau started the game. According to the Seattle Star, “Engel was very careful to let the Keio boys know that Kato, his pitcher, was deaf and dumb. But later in the game Kato became enthused, as ball players will, and the jig was up when he began to root in good English.” Nonetheless, Cadreau handled Keio relatively easily, striking out 13 en route to a 6-3 victory.

Throughout the spring and summer, the Nippons continued to face the area’s top teams, including the African American Keystone Giants, to prepare for the trip to Japan. Yet in their minds, the most important matchup was the three-game series against the Asahi for the Japanese championship. The Nippons took the first game, 4-2, on July 12 at Dugdale Park but there is no evidence that they finished the series. Not to be outdone by their rivals, the Asahi also announced that they would tour Japan later that year. Sponsored by the Nichi-nichi and Mainichi newspapers, the Asahi would begin their trip about a month after the Nippons left for Japan.

The Nippon left Seattle aboard the Shidzuoka Maru on August 25. Their departure went unreported by the city’s newspapers as international news took precedence. Germany had invaded Belgium on August 4, opening the Western Front theater of World War I. Throughout the month, Belgian, French, and British troops battled the advancing Germans. Just days before the ballclub left for Japan, the armies clashed at Charleroi, Mons, and Namur with tens of thousands of casualties. On August 23, Japan declared war on Germany and two days later declared war on Austria.

After two weeks at sea, the Nippon arrived at Yokohama on September 10. The squad contained 11 players: George Engel, Frank Miyasaka, Yukichi Annoki, Kyuye Kamijyo, Masataro Kimura, Ken Kitsuse, Mitsugi Koyama, Yohizo Shimada, Kiichi Suzuki, Sadaye Takano, and Masashi Takimoto. Accompanying the ballplayers was the team’s cheering group, consisting of 21 members and led by Yasukazu Kato. The group planned to attend the games to cheer on the Nippon and spend the rest of their time sightseeing.

As the Shidzuoka Maru docked, a group of reporters, Ryozo Hiranuma of Keio University, Tajima of Meiji University, and a few university players came on board to welcome the visiting team. The group then took a train to Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, where they were met by the Keio University ballplayers at 2:33 P.M. The Nippon checked in at the Kasuga Ryokan in Kayabacho while the large cheering group, which needed two inns to accommodate them, settled down at the Taisei-ya and Sanuki-ya.

Only two hours later, the Nippon arrived at Hibiya Park for practice. Not surprisingly, after the voyage they were not in top form. The Tokyo Asahi noted, “Even though the Seattle team is composed of Japanese, their ball-handling skills are as good as American players, and … their agile movements are very encouraging. … They hit the ball with a very free form, but yesterday, they did not place their hits very accurately, most likely due to fatigue. … The Seattle team did not have a full-fledged defensive practice with each player in position, so we did not know how skilled they were in defensive coordination, but we heard that the individual skills of each player were as good as those of Waseda and Keio. In short, the Seattle team has beaten Keio University before, so even though they are Japanese, they should not be underestimated. On top of that, they have good pitching, so games against Waseda University and Keio University are expected to arouse more than a few people’s interest, just like the games against foreign teams in the past.”

The Nippon would stay in Japan for almost four months, but the baseball tour itself consisted of just eight games—all played during September against Waseda and Keio Universities. The players spent the rest of the time traveling through their homeland and visiting family and friends.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website