by Yoichi Nagata, Mark Brunke and Rob Fitts

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. Today Yoichi Nagata, Mark Brunke and Rob Fitts focus on the two Native American baseball tours of Japan which both took place in 1921. This article was selected as a winner of the 2023 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

In the late nineteenth century as the American frontier closed, the myth of the Wild West began. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, dime novels, and, later, Western movies created a fictitious past dominated by stereotypes of cowboys, gunslingers, and Indians. In most of these genres, Native Americans were depicted as exotic, almost non-human, wild and cruel savages. This stereotype proliferated throughout the United States, Europe, and even Japan. Nonetheless, Wild West entertainment became popular throughout the United States and Europe. In 1921 two baseball promoters tried separately to capitalize on this international fad by bringing Native American baseball teams to Japan. But neither tour turned out as planned.

The genesis for these tours took place on the Nebraska plains in 1895 when Guy Wilder Green, a law student at the University of Nebraska and player-manager of the Stromsburg town baseball club, organized a game against the Genoa Indian Industrial School. To his surprise, “Even in Nebraska, where an Indian is not at all a novelty … when the Indians came to Stromsburg, business houses were closed and men, women and children turned out en masse. … I reasoned that if an Indian base ball team was a good drawing card in Nebraska, it ought to do wonders further east if properly managed.” After graduating from law school in 1897, Green created the All-Nebraska Indian Base Ball Team (soon shortened to the Nebraska Indians) which became one of the nation’s most popular barnstorming baseball clubs. From 1897 to 1906 the Nebraska Indians played 1,637 games in 17 states and Canada.

In 1906 much of the United States was enthralled by all things Japanese. Japan had just emerged as the improbable victor in the Russo-Japanese War, and the Waseda University baseball club had recently toured the West Coast. Green decided to capitalize on the fad by creating an all-Japanese baseball club to barnstorm across the Midwest. It became the first Japanese professional team on either side of the Pacific, as pro ball would not come to Japan until 1921.

Although Green would advertise that he had “scour[ed] the [Japanese] empire for the best men obtainable,” he did nothing of the sort. In early 1906 Green instructed Dan Tobey, the Caucasian captain of the Nebraska Indians, to form a team from Japanese immigrants living in California. Led by player-manager Tobey, Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team embarked on a 25-week tour that covered over 2,500 miles through nine Midwestern states as they played about 170 games against town teams and independent clubs. Despite success on the diamond, Green disbanded the club at the end of the season. Two members of the squad, Tozan Masuko and Atsuyoshi “Harry” Saisho, went on to organize their own Japanese barnstorming teams and eventually the Native American tours of Japan.

TOZAN MASUKO AND THE 1921 SUQUAMSSH TOUR

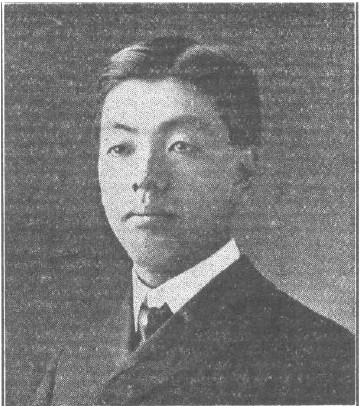

Born in 1881 in the village of Niida in Fukushima Prefecture, Tozan Masuko spent most of his childhood in Tokyo, where he became enamored with the newspaper industry.To further his education, he came to the United States on his own at the age of 14 in 1896. He attended an American high school, where he fell in love with baseball. After graduation, he became a reporter for Shin Sekai in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles to work for the Rafu Shimpo in 1904. There, he joined the newspaper’s baseball team and accompanied Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball team during its 1906 barnstorming tour, occasionally filling in as a utility player or umpire.

In 1907 the Rafu Shimpo transferred Masuko to Denver, where he decided to create his own professional Japanese barnstorming team. The Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team played 22 games in the summer of 1908 in Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri before rain cut its season short. The following year, he teamed with Harry Saisho to organize another barnstorming team called the Japanese Base Ball Association, which planned to tour the Midwest. That tour also failed after just a few games. During both tours, Masuko tried to promote the teams with exaggerations and outright lies, claiming his squads of local immigrants were “composed of the best nine players from the Japanese Empire … picked from the colleges of Japan … straight from the Orient.” Tozan remained in Denver as editor of the Denver Shimpo for nine more years before moving to Salt Lake City to become editor of the Utah Nippo in 1917. By 1920, however, Masuko had moved to Yokohama, Japan. Drawing on his past experience promoting the Mikado’s and JBBA baseball teams, Tozan decided to become a sports promoter. The endeavor did not go well: A tendency to exaggerate and a lack of scruples got in the way.

Masuko began his new career by bringing Ad Santel and Henry Weber to Japan to “test the relative merits of American wrestling with Japanese jujitsu.” Santel, who is still considered one of the greatest “catch wrestlers” of all time, was the reigning world light-heavyweight champion. Since 1914 he had been wrestling Japan’s top judo champions—often defeating them easily. As a result, he was well-known in Japan. Weber, a 6-foot, 200-pound blond who “looked like a Greek god,” was not Santel’s equal on the mat but was nonetheless a renowned wrestler and Santel’s manager.

A large crowd met Santel and Weber on the pier as they arrived in Yokohama on February 26, 1921. Beneath banners bearing the wrestlers’ names in both English and Japanese, kimono-clad girls presented the visitors with wreaths of flowers and bouquets as the crowd cheered “Banzai!” Tozan accompanied the wrestlers to Tokyo, where they would spend the next week preparing for a match against Japan’s experts from the Kodokan Judo Institute—the school created by the sport’s founder, Jigoro Kano.

Although Masuko had arranged for a prominent judo expert to provide opponents for Santel and Weber, he had never contacted the Kodokan itself. Members of the school were outraged when they heard of Masuko’s plans. Kodokan representatives decreed that any student who took part in the match would be expelled, as “the spirit of Bushido prevents … taking part in any professional show of judo.”

Despite the edict, several judo experts accepted the challenge and wrestled Santel and Weber on March 5 and 6 at Yasukuni Shrine. Sellout crowds of 6,000 to 8,000 attended each day, bringing in an estimated 24,000 yen. After the matches, the wrestlers asked for their 35 percent cut of the gate receipts plus reimbursement for their travel expenses. Masuko, however, claimed that the matches had produced a profit of only 196 yen and promised to pay when cash became available. They next went to Nagoya, where Tozan had arranged two more matches. Despite strong attendance, the wrestlers still did not receive their money. A few days later in Osaka, Santel and Weber refused to enter the ring unless they were paid upfront. Masuko coughed up 300 yen and the matches took place. Noting the large crowds, the wrestlers demanded 1,000 yen prior to the third match. After much wrangling, they eventually accepted a check from a local promoter.

The next morning, when Santel presented the check at the bank, he was told that the promoter had no account, making the check worthless. Returning to the Osaka promoter’s office, Santel learned that Masuko and the local promoter “had drawn on the money due to them until there was nothing left.” The American wrestlers searched in vain for Tozan, who had left Osaka and gone into hiding.

A sympathetic judo expert stepped forward and arranged bouts to raise enough money for Santel and Weber to return to the United States. As he left, Santel told reporters, “Our stay in Japan has been very pleasant in some ways, and we will not carry away the impression that everyone here is bad. … There are swindlers everywhere and we just happen to become connected with two in Japan.” Santel and Weber declined to bring charges against Masuko as legal fees and further time in Japan would have been prohibitively expensive.

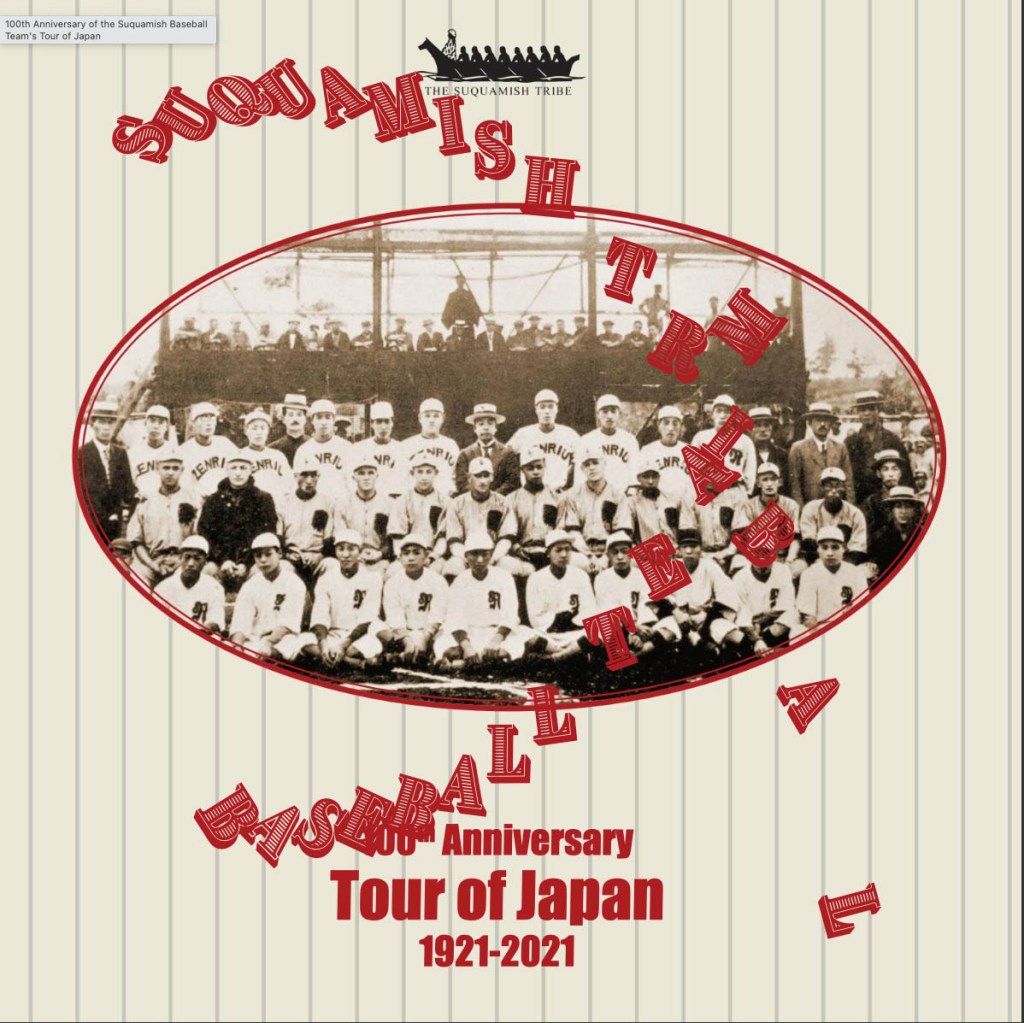

A few months later, Tozan once again brought athletes to Japan. This time he returned to the sport he loved and planned to bring the first Native American baseball club to Japan. On July 2, 1921, he arrived in Seattle on board the Fushimi Mara. By the first week of August, Masuko was making arrangements for a team of Suquamish Indians, a group of Native Americans from the western shores of Puget Sound, who had been playing baseball since the late nineteenth century, to accompany him back to Japan. How Masuko learned of the Suquamish team is unknown, but the Bremerton Searchlight reported, “In their efforts to secure an all-Indian ball team for the trip, the promoters have tried out practically every Indian ball team on the coast and the fact that the Suquamish team was finally chosen is a considerable boost for the local players.”

Masuko, who said he was a representative of the Sennichitochi Real Estate and Building Corporation of Osaka, claimed the Suquamish were being invited by Meiji University.

Howard Myrick, who ran the Seattle branch of the A.G. Spalding & Brothers sporting-goods company, was responsible for assembling the squad but the exact relationship between Masuko and Spalding is unknown. The Suquamish players believed their contracts were with Spalding, but, to their chagrin, that would not be the case.

On the morning of August 6, 1921, at 10 A.M., Masuko and the Suquamish ballclub boarded the Alabama Mara at Pier 6 in Seattle and sailed for Yokohama. The squad was an amalgamation of teenage outfielders, semipro veterans, and a legendary pitcher who was called “the Chief Bender of the Northwest.” He threw a fastball, a curve, and a signature pitch called the “clam ball” that would rise as it approached the hitter.Accompanying the Suquamish was a semipro team from Ballard, Washington, that had been renamed the Canadian Stars for the Japanese visit.The teams planned to stay in Japan for about two months.

The Canadian Stars and the Suquamish teams were familiar with each other. They met two weeks earlier on July 24, with the Canadian Stars, at that time called the Ballard Merchants, winning, 11-3. The game was started by the main pitchers for both teams. The purveyor of the “clam ball,” 31-year-old Louie George, started for Suquamish, and a future major-league pitcher, 24-year-old Rube Walberg, in a breakout semipro season that would catapult him into professional baseball, started for Ballard. The Suquamish had Arthur Sackman pitching relief and Lawrence Webster was at catcher. The game was previewed in the Seattle Daily Times on July 22, giving us an idea of the perception of the Suquamish style of play: “The Ballard Merchants are going to Suquamish, looking for an easy game, but you never can tell about Indian ball players, as they do not do what is expected of them. In some cases, they break up all kinds of defensive plays by hitting pitch-outs for home runs and making their opponents very uncomfortable.” The Suquamish team was referred to in the same newspaper as being “made up of the best Indian ball players in the Northwest.”

The regular Suquamish team that competed in Seattle area semipro games formed the core of the team that traveled to Japan. Many of their regular players, however, could not travel for two months because of work and stayed home. Enough players stayed behind that the Suquamish had a separate team that continued playing to the end of the semipro season in October.

Seven players on the touring team were members of the Suquamish Tribe: Lawrence “Web” Webster, 22 years old, catcher and outfielder; Charles Thompson, 28, third base and shortstop; Harold “Monte” Belmont, 18, outfield; Roy Loughrey, 20, outfield; Woody Loughrey, 17, outfield; Richard Temple, 18, center field and utility; and Arthur Sackman, 17, outfield and pitcher. The five younger players had experience playing baseball at Indian boarding schools.

Needing to supplement the core of the Suquamish club, the team brought along Louie George and four nonnative players—known as “boomers.” The 31-year-old George was a member of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and, according to the Seattle Daily Times, “is the star of the team. This pitcher is a veteran of many tight pitching duels with Seattle hurlers, having played with Indian teams for years. He also is a heavy slugger and a good outfielder.” Having lost the end of his thumb in a motorcycle accident, George threw an unusual pitch he called a “clam ball.” His nephew Ted George remembered, “It was a pitch that rolled off a shortened thumb at a unique angle … rising as it approached the batter. … It befuddled hitters … and when mixed with a blazing fastball and killer curve became stuff of legend.”

The nonnative “boomers” were 31-year-old Lee “Bill” Rose, first base, catcher, and utility, who became the team’s captain; 27-year-old Roy “Cannon Ball” Woolsey, pitcher, outfield, and coach; 27-year-old James C. Smith, second base; and 23-year-old John Lukanovic, outfield, first base, and pitcher. All four were longtime Northwest Coast semipro players.

Woody Loughrey recalled that during the 16-day trip to Japan, the squad “worked out on the ship, out on the open deck. See it got pretty rough all right” and on “the better days, why, we worked out up there playing catch and running up and down the deck.” Lawrence Webster added, “[T]hat continued rise and fall of those boats itself was awful monotonous, so we started playing catch on the boat. And we started out with about three dozen baseballs so we could keep our arms in shape. By the time we got over there, we had two, just two, not two dozen. That’s all we had [the rest went overboard]. So we hung on to those two and we got over, and we got some new ones that was made over in that country. And there was quite a bit of difference in the baseball. While the size was practically the same, theirs was dead, you’d hit it and it wouldn’t go very far.”

The two clubs arrived in Yokohama on the steamer Alabama at noon on August 22,1921. The Suquamish immediately went to their inn to change into uniforms and then to the Yokohama Park Grounds to practice. “A big gathering of Japanese fans” waited at the park “to give the invading teams an enthusiastic welcome … and to watch their every movement with bat and glove.” The clubs were expected to stay in Japan for two months, playing collegiate teams in Tokyo and touring the country.

Promoter Tozan Masuko bragged to reporters that he had a big tour planned and that his powerful Native American squad would battle against the top Japanese teams. “The tour would start in Tokyo against Meiji University, and then the Indians will play Waseda, Keio, Hosei and Rikkyo Universities, Mita and Tomon Clubs and others. After the Tokyo series, they will go to the Tohoku region with Meiji University, playing in Fukushima, Morioka, Hokkaido, Niigata, and Nagaoka before heading to Kansai for games against Daimai and Star Clubs and other teams. Though depending on circumstances, they are eager to barnstorm even in Shikoku, Kyushu, Manchuria and Korea.”

But none of this was true. Meiji University had neither committed to sponsor the tour nor travel with the visitors to Tohoku. In fact, Masuko had not arranged any games and would put together the schedule on the fly.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website