by Robert K, Fitts

As a player I had kind of an up and down career. I played a year and a half, two years, in the big leagues, off and on, and it just didn’t look as though that [an MLB career] was going to happen. I played for Charlie Manuel, who managed the Phillies in the World Series and had played in Japan as well. He was managing Cleveland Indians AAA team, and he wanted me on his team. I ended up being kind of a utility player. I went to him and said, “Hey man, I would love to play in Japan.” I was really not the prototypical player to go to Japan because they wanted a Jessie Barfield or Lloyd Mosby, those type of guys. But Hiroshima is a smaller market, and they had an interest. When their scout came over to see me, I performed very well, and he signed me.

When I went over, I really went into it wholeheartedly. I wanted to make a good impression. I did all their practice stuff. I was doing everything. Man, at the end of the year I was tuckered out! It was just their workload, what they did, plus we practice differently. Americans here practice full tilt, like in a game, whereas Japanese sometimes back off. They get a lot out of 70%. That’s just how they practice. You hear about some of the ridiculous things that they do, like they’ll go take 1000 swings, right? Well, there’s nobody that can do that full tilt. One of the examples on the pitching side, is Hiroki Kuroda, who pitched for me when I was managing. He just had a chip removed from his elbow and on his first day back, he said, “I want to throw a 100-pitch bullpen.” I said, “Why would you want to do that?” “Don’t worry,” he said, “I’ll throw probably 15 full tilt. I’ll back off on everything else.” He just wanted to show the press that he was healthy. That was very important to him.

I didn’t know a lot about Japanese baseball before I went over. I knew Mr. Baseball and I had friends who had gone over; some were successful, some weren’t. The guys who were really successful in the States were not always so successful in Japan. There was a different mindset when it came to Japanese baseball, as opposed to American baseball. I think the speed of the game in the United States is obviously faster. Players can adapt to the speed of the game, whereas in Japan they have a way of being successful that works for them and that’s what they want to do. They don’t deviate from that very much. It’s a kind of old school like mid 1940s. They still practice a lot that way.

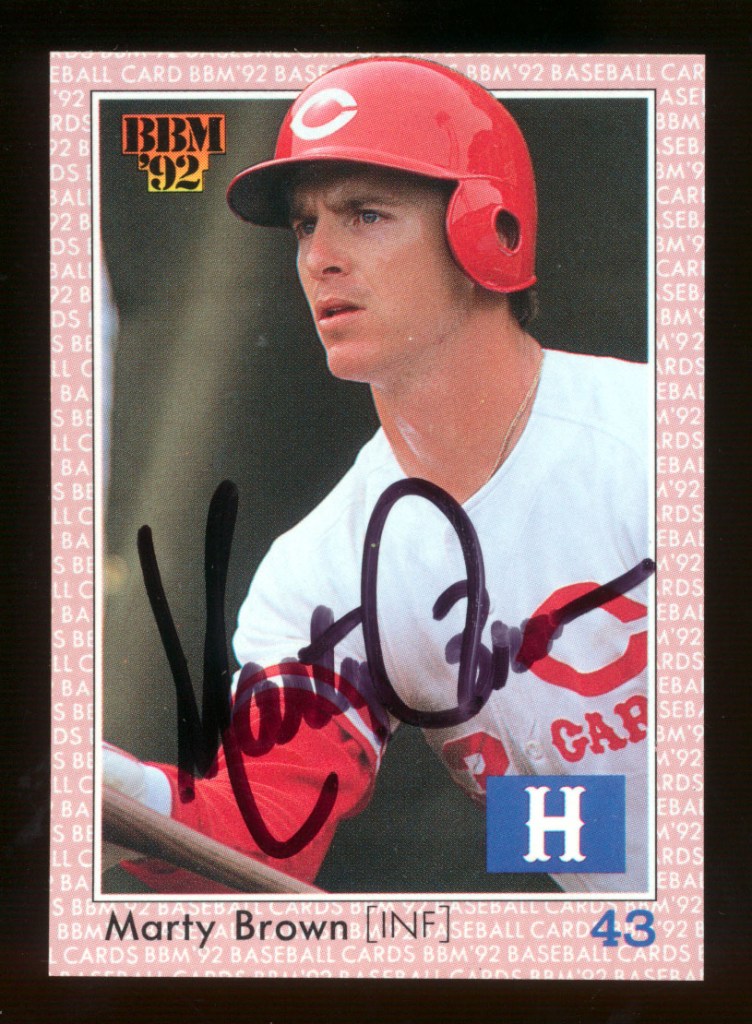

[When I joined the Carp in 1992] everybody was upbeat about how the team had done the year before. [They had won the Central League pennant]. I had some really good teammates, like Tomonori Maeda and Kenjiro Nomura. Akira Etoh was there. He led the league in home runs, and I hit behind him normally. 1992 was a pretty satisfying year for me individually. I had a pretty good season. There were a lot of really good players, but we had aging pitching staff. Manabu Kitabeppu was getting older. It was unfortunate that we just kind of ran out of pitching, because we had such a good nucleus of position players. We just didn’t have enough bullpen [arms] to really take care of the bigger-tier teams. The Giants were difficult, and the Swallows were really a good team at that time with Atsuya Furuta and their manager [Katsuya] Nomura-san. So, it was a really challenging season, but we played well. It was a lot of fun and I really enjoyed Hiroshima, especially the fans and the atmosphere. That was pretty cool. The following year [1993], we had some issues with injuries, myself included. That was difficult.

I was always an aggressive player. It’s just the way I’ve always played. I think a lot of players on the Japanese teams were surprised because it was not the norm. I can remember, [early in the season] scoring from first base on a double. As I came into home, the ball was getting there just as I came to the plate and I knocked the catcher over. The ball popped out and I scored, and we ended up winning by a run. People didn’t like the fact that I knocked the catcher over. But as I got up, I tried to see if I could help because I think I broke his collar bone. Everybody could see that I was trying to help him because it was a televised game against the Giants. So, everybody saw me as being hardnosed and they just knew how I played. They were pretty accepting. I think some of the fans in Hiroshima actually enjoyed it.

When I was a player, there was a veteran locker room in Hiroshima, and there was a rookies locker room. The rookies didn’t stay with the veterans unless the rookie had a friend who was a veteran. I was in the veteran locker room. It was very small and all of my teammates smoked like fish! [As a foreign player] you can feel isolated sometimes, and you have to learn how to live with it. I didn’t speak the language very well at all. Also, I was by myself. Louis Medina got hurt his first year, so I didn’t have a teammate. Robinson Checo, a young Latin kid came over, but he didn’t know any English. They called me in to interpret for him, but I didn’t know Spanish! So, I went in and said, “Que pasa?” That’s about all I knew. There were a lot of really quirky things like that that happened over there.

After I stopped playing, I managed in the Minor Leagues. As a AAA manager in Buffalo, we had some good teams. In 2004 we won a championship and in 2005, we had another good team, but we ended up losing in the playoffs. A good friend of mine, Erik Schullstrom was a scout for Hiroshima, and he said, “How would you feel about managing for the Carp?” I said, “Oh, man, that that would be a great opportunity. I’d love to do that.” He went back and introduced the idea to the owner (I had played for his father). He came to Charlotte, and we had an interview, and they said “Yeah, let’s do this.” That’s kind of how it went down. It was a little difficult at first.

I think I was kind of a stopgap until they got a Japanese manager in there after I was gone. I don’t think it was ever intended for me to win as a manager. I think in their mind they just wanted to try to get somebody else ready and then when they were ready, they could go ahead and kick me loose, which that was fine with me. Didn’t have a problem with that. It was what it was. I thought we did a lot of really good things and I enjoyed my time there as a manager and a player.

Koji Yamamoto was my manger when I played for the Carp and also managed just before I was hired in 2006. Yamamoto is just a super guy. The two nicest people I was around in baseball would be Sadaharu Oh, who I managed against, and Yamamoto-san. He really wanted me to help [the Carp], and he was very positive about me coming over there. That was pretty cool. As an American managing in Japan, some guys get paranoid because they think somebody’s going to do something to sabotage [the changes] they’re trying to get through. I didn’t have that. Some of my coaching staff were former teammates of mine and they wanted to see change. The Carp hadn’t won in a while and so they wanted to see an American way of doing things and then get back to Japanese style at some point refreshed.

The way Yamamoto would work the bullpen, it was about complete games. For example, he would leave Hiroki Kuroda in to complete a game because Kuroda at 60% was better than everybody else in the bullpen. Yamamoto-san wouldn’t even go down and ask Kuroda if he was okay. He would just leave him in there. And Kuroda wasn’t going to say anything. He just kept doing it. I got to manage Kuroda for a while, and said, “Would you rather go through and face these guys, the meat of the order, for the fourth time in the ninth inning when you’re dead tired, or would you rather hand it over to the bullpen when you’ve done your job for that day with a certain amount of pitches? That keeps you healthier.” We even tried him on four days rest. We didn’t really have to, but we tried it just because he wanted to show people in the States that he could do it. And he did okay. He was just not used to it. He was used to pitching every Sunday. That’s another thing that’s different over there, the rotation and how they worked it. Star players were always going to pitch on Sunday, and they announced their pitchers. There were never any flip flops or any of that. As a manager I didn’t understand that. The ownership was like, “Well, [the fans] want to know when they’re going to pitch.” And I said, “Well, they will come [to the ballpark] anyway.” We went through this one time, when Kuroda, pitching on short rest, pitched on a Saturday. It’s just a different mindset. I did it a little more of the American way when I was there, but I [ultimately] did what the owner wanted to do. It was his team.

When I played, [most Japanese pitchers threw a] four-seamed fastball and a slider, sometimes a breaking ball like a curveball, and some guys would throw a change up. That’s kind of how everything was when I was a player, but as I started to manage, it was different. The players wanted to experiment with the split finger. They wanted to take their repertoire up a notch. Kenta Maeda, Masahiro Tanaka, Hisashi Iwakuma, and Kuroda, I managed all those guys, were the top line pitchers in Japan, and they always wanted to experiment with new pitches. That was really never brought up back when I was playing. So, it was good to see how it evolved like that. I think it was good for them and a lot of those players were motivated to get to the States and play. All four of those guys did.

Takahiro Arai was one of my favorite players in Hiroshima. The year before I managed, Arai had won a home run title. The first year I managed, Jeff Livesey was the head coach. Jeff had just showed up to spring camp at Nichinan, so we dressed up one of our interns in Arai’s uniform. He was really skinny, and Arai was a big guy. We got it all set up and I told Jeff, “This guy is the home run king, and he wants to take batting practice strictly for you because you’re going to be the hitting coach and you haven’t seen him hit.” Jeff saw the intern and he went, “Man, he’s not a real big guy, is he?” I just said, “No, no, he’s not that big.” The intern got in there and he swung at the first three pitches and missed them. He was slamming his bat and doing stuff that the Japanese players just wouldn’t do. He was great. He was a good actor. Finally, he popped one up and he pretended like it was going to be a home run but it didn’t get out of the infield. Jeff [was looking worried]. Finally, Arai came out and introduced himself, and then Jeff realized that the guys have tricked him. That was a really funny moment. We tried to lighten things up because Japanese don’t normally do stuff like that. We tried to have a lot of fun, but we worked really hard too.

I named some co-captains the first year when I was manager. I named Tomonori Maeda and Hiroki Kuroda captains because they didn’t get along. Maeda didn’t really want to do any of that. Whereas Kuroda took charge, and he would say, “Hey, we need to do this” and would come into my office and talk to me about stuff. Those two guys really were good. Maeda and I were actually teammates when I played. He was an outstanding center fielder. He could play. When he was only 17 years old, 18 years old, he was a stud. He had all five tools. He could run, could throw, could hit, could hit for power. He was really a top tier player, but he didn’t say anything because he was a young player. He wouldn’t say anything out of the ordinary to ruffle any feathers back then. When he was young, he was an MLB caliber player. If he went over [to the States], he would have had to get adjusted, and that would be the only fear I would have had, that he couldn’t adjust to the American type of playing. He had to do things his own way and that didn’t fly in the United States back then like it does today. He could still play at times [when I managed him], but he couldn’t play in the field anymore. He got to the point where he was kind of just a pinch hitter. The Hiroshima people loved him. He was a mainstay there.

Tomoaki Kanemoto was also a teammate of mine and then I managed against him. When Kanemoto became free agent after the 2002 season, the front office had to make a decision between resigning Maeda or Kanemoto. That was a difficult thing. The owner chose Maeda, whereas Kanemoto went on to be the next Cal Ripken with Hanshin. A lot of people really wanted to see Kanemoto stay. I would have loved to have had him on my team because he was a good friend of mine. He had tools and he was strong. You could see that he was going to be a good player.

Having a small budget has always been a challenge for Hiroshima. I played for Kohei Matsuda, the father of the current owner, before he passed. He would go out and get a player if he thought a foreign player could help them win. He wouldn’t care about spending money to get him. It whereas the ownership now is more constrained. So, I never had the opportunity to pick out an American player when I was the manager. You might think that was kind of weird. I had some good players, but we didn’t get that frontline American player that I thought would take us over the top.

I never managed at the Major League level in the United States. I spent a lot of time in AAA and AAA is more of a development type situation. I always showed up every day to win but I never sacrificed development for winning. If we weren’t winning, I was not going to take the number one, two, or three prospect out of the game. I might give him a day off, but I was not going to take him out of the lineup. I think that’s just an understanding of everybody who is in development in the United States. That’s what they truly believe. Development was a big thing for me, and I knew we had to do that in Hiroshima as well. I just had to figure out a different way to do it. So it was different in that respect. I think the players did have a bit of a challenge, me being American and wanting to do things a little bit differently at times, but I didn’t do it all the time. I tried to make adjustments.

For example, in Japan all of the teams take infield [practice] the same way. They never vary from that, and they take infield every day. Very seldom at the Major League level do teams take infield anymore. If guys want to get in some early work and take some ground balls, or maybe some fly balls if they are an outfielder, they’ll get those in before practice even starts. Even as a Minor League manager I didn’t have my guys take infield every day, but I had them do it often because they were developing. I tried to introduce American-style infield drills to the Carp. We an American style infield [drill] one day and then we would go back and do the Japanese style infield. They didn’t like the American infield. It wasn’t the same. But they could do it and never miss a ball. It was pretty amazing how they could do it, but they just liked it their way. I just finally gave up and said, “Yeah, let’s do it your way. You guys look clean with it.”

When I started, the team was not in good working condition. They had walked over 500 people the year before I got there, and when you play in a little stadium, like Hiroshima, that makes things very difficult. You can’t walk that many. It leads to giving up three-run homers every other inning. That was their demise. But we got them back on track by making sure we pitched ahead in the count. We cut our walks down to just under 400. When our pitchers had a 2-2 or 3-2 count, they were always looking for a swing and a miss, but we really didn’t have strikeout type pitchers. We had contact type guys, but they didn’t really understand that. They thought they needed a swing and miss to not give up a hit, and that wasn’t the case. Working on that improved us tremendously during the first year when I started managing.

I also wanted to get rid of the hogwash. Like we would practice for six hours a day, finish up, and guys would be dead tired, and somebody would tell them that they needed to go to the parking lot and keep swinging the bat for another hour. I thought that was a waste of time. Get your rest, get something good to eat, and get ready to work hard the next day. So, I started taking them to the pool and making them swing a bat in the pool after they got done with practice. Some guys liked that, some guys didn’t. The point was they were not getting anything out of sitting in the parking lot, smoking cigarettes and swinging a bat. That was not really what we needed. If you’re going to do something, do it with purpose. I think I brought some of that to the table. It wasn’t as though I was trying to change everything. I just didn’t understand how come there wasn’t any change. But when it came down to it, it was a Japanese team and I was an American manager so I would just try to introduce ideas.

Some of the Japanese managers would do things that you would never see in the U.S. For example, one of the Dragons better hitters was a two-hole hitter. When he would get on base with one out, the Dragons manager Hiromitsu Ochiai would bunt his three-hole hitter and then let the four-hole hitter come up with two outs. I was like “Hell, yeah, that’s perfect for us!” With two outs all we had to do was get that guy out and the inning was over, or don’t pitch to him at all, and go for the next guy. [But my pitchers would insist on pitching to him] and that four-hole hitter would get a hit. It never failed. I would ask my pitchers, “Why are you doing that?” It was almost like an unwritten rule that they couldn’t put him on and couldn’t pitch around him. They had to make him swing at their pitch and get him out. That was very discouraging to me. Ochiai just kept doing it. I was like, “God Dang it. What are you doing here?” It was so different.

The way they would line up defensively was also different from in the U.S. You would see a third baseman playing even with the bag, right next to the bag, and there would be nobody out with a leadoff hitter up or the seven or eight-hole hitter up. Why would you do that? [Well] they were actually looking for a ball to be hit off the end of the bat. They just wanted to cover everything. But you have got to give something up to get something. You want to double play ball? Then, you have to cheat and get to double-play depth. That’s just the way we treat the game over here. To them, it’s not an option. They were going to cover every possibility. If there was a swinging bunt, they were going to cover it.

They would try to take away a double by staying on the line but that would leave a huge gap on the left side of the infield. I was like, “Guys were kind of kicking ourselves in the throat here. What are we doing?” A few little things like that I would change around, but it was very difficult to get them to understand it, especially the veteran players. They had a way to position that they were used to. They would want to play at a certain place on the field, and I’d be like, “Well, that doesn’t make sense. You’re giving up too much.” That was a little frustrating, but I got through it. It was not a big deal.

Here’s one thing that I had never seen happen before [I went to Japan]. When I managed, there were some players who if they had a few bad outings or maybe they weren’t hitting really great would come into my office and say, “Hey, think I need to go down to the minor leagues for ten days and then I’ll come back.” They might not pick up a ball [down there] but when they came back, they were just kind of regrouped and refreshed and they went out and did what they used to do. That’s way different from what we do in the States. I never imagined that that would happen.

My closer did that to me one time. He had already blown two saves, and he blew another lead, but we ended up coming back to win the game. He came into my office and said, “I think I need to go to the minor leagues.” And I said, “Do you want me to tell the media, or do you want to tell them? He said, “I’d rather you tell them.” So, he threw me under the bus. I told management about it, and they didn’t think anything about it. They were just fine with it. They said, “He’s not been very good. Maybe he needs a little rest.” So, I think it was probably normal for a Japanese player to do that if he’s had some failure. Can you imagine somebody doing that here? I was blown away.

Overall, I got along great with the umpires in Japan, but we all have situations in which you get heated on the field and if you don’t then something’s wrong. [As a manager] you’ve got to show your team and your players that you are willing to fight for them and it’s us against them. And if they’re not going to make a proper call, then you have a right to say what you need to say. There was a particular umpire, I won’t mention his name, who had trouble seeing. He’d make a really bad call, and I’d ask him in so many words, “Are you ***ing blind!?” And he would look at me and, I almost felt sorry for him, say, “Yeah, I can’t see very well.” I was like, what the hell? I’ve never had an umpire say that before!

I would go to the umpiring group and ask them the rulings on something or what they saw in a certain situation. I got along with them fine. I would go over and talk to the guys who had thrown me out of games. It was no big deal. Japanese managers didn’t really do that. They would go out and bump them and hit them, and then they would stay in the game, whereas I would just talk to them and get thrown out. I think my interpreter got me into more trouble than what I really did. He would get fired up more than I would, and he’d say stuff and it looked like I was saying it, and I wasn’t really saying it!

[Editor’s note: Marty became famous throughout Japan on May 7, 2006, for throwing first base during a dispute with the umpires].

Well, I had an American pitcher, Mike Romano, on the mound and there was a close play at first base and the umpire called the runner safe. He was one of my favorite umpires over there. His name was Katsumi Manabe. I didn’t know if he was safe or not, it was a tough call. Manabe didn’t know English that well, and I think Mike said, “Well, that was a fucking horseshit call!” Well, Manabe thought that Mike was calling him that. It was just the third inning and Manabe threw my starter out of the game. I went out there, and I’m like, “Oh, God, I’ve got to waste some time here so we can get somebody warmed up enough to get them in the game.” So, I started arguing with the umpires, and as I was arguing with the umpires, I noticed they all had stopwatches. I didn’t know what the hell they had those stopwatches for. Anyway, I was talking, and I was getting heated up, but I still was going to have to waste some more time because we were not going to have anybody ready soon.

Finally, the umps said, “That’s enough. You need to go back to the dugout.” I was like, “What?” And they said, “Yeah, your time is up. You can’t go over the amount of time to argue this call.” So, I was like, “Oh, you’re not going to throw me out after all the hell I put you through here?” They just looked at me, and said, “You’re done.” And they started walking away. I had to figure out a way to waste more time, so I just picked up first base and threw it out into right field. All four of them threw me out at once! All four! That was the first time that had ever happened.

The Carp’s owner made red T-shirts that said, “Danger! My manager throws bases.” He put that out there and they sold them as souvenirs. Pretty good marketing idea. That didn’t bother me any. What did bother me is that first time I got tossed, they finned me 1000 bucks. And the next time I got tossed, it was going to be 2000. My coaching staff thought it was great when I got tossed and the team really liked it. It showed some energy because none of the other Japanese managers really did that. I went to the coaching staff, and I said, “Listen, I can’t do this anymore.” So the coaching staff got together and they paid my fine. I thought that was pretty amazing. They didn’t say anything to the players. The coaches leaked it out that I didn’t feel that I could get tossed because management was not going to help pay the fines. Well, management ended up coming back and said, “If we feel that it’s a worthy cause and you can get tossed, we’ll pay your fine.”

With the history of the city, and the bombing, the culture of Hiroshima is about rebuilding and fighting. “We’re not giving up!” I think that really stands out in Hiroshima and with the fans there. The fans make trips to Tokyo, and they have their own cheering section. They’re just great. If I had to compare them to a team in the States as far as fan base, I’d say the Cardinals. The reason I say that is the Cardinals do very little during the course of the winter to get better, but it always seems to work out because their fan base is behind them all the time and a lot of guys just need that little extra jump. So yeah, Hiroshima is just a special place. I think it’s more about the people there. I think the rebuilding of the team and putting the money back into the team now has really helped them as far as competing in the league. Hiroshima’s new stadium is off the wall great. It’s awesome. Nippon Ham’s new stadium is also really good. With Japan’s culture, loving baseball the way they do, making all these new stadiums and places for the fans to go has been pretty amazing.

My time in Japan was a really enjoyable experience, both as a manager and as a player. I really did love it. Also, I met my wife there, so I brought the best part of Japan home with me!

Read more Carp Tales on Rob’s blog