by Dave McNeely (npbcardguy)

This great introduction to current Japanese baseball cards was published on SABR’s Baseball Card Research Committee’s Blog earlier this week,. We have decided to repost it here as background for our zoom chat with Tatsuo Shinke the CEO of Mint Sport Cards to be held on Wednesday, January 28 at 8:30 pm EST. Please see the Asian Baseball blog for more information.

Baseball has been played in Japan for over 150 years and professionally for the past 90. There are known to be baseball cards depicting the sport in Japan as early as 1900 although little is known about many of the pre-World War II cards simply because few of them survived the war. The post-war era featured an explosion in baseball card production that has continued to this day.

Doing a search for “Japanese Baseball Cards” on Ebay will give you a huge number of results and it can be kind of overwhelming trying to make some sense of what you’re looking at. How many card companies are there? How many different sets are there? Are Yomiuri and Hanshin places in Japan? This post will attempt to answer some of these questions by giving an overview of the current state of the Japanese card market.

Baseball In Japan

Let’s start by giving a little bit of background information about professional baseball in Japan. Generally when people talk about baseball in Japan, they are talking about Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB), the Japanese equivalent of MLB. NPB consists of 12 teams in all that are split into two separate six team leagues – the Central League and the Pacific League. The Central League teams are the Yomiuri Giants, the Tokyo Yakult Swallows, the Yokohama DeNA Baystars, the Chunichi Dragons, the Hanshin Tigers and the Hiroshima Toyo Carp. The Pacific League teams are the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles, the Chiba Lotte Marines, the Saitama Seibu Lions, the Orix Buffaloes and the Fukuoka Softbank Hawks. The team names may seem a little confusing but the thing to remember is that all the team names contain the name of the company that owns the team (Yomiuri, Yakult, DeNA, Chunchi, etc) and several of the team names also feature either the city, prefecture (more or less the equivalent of a state) or region (think something like the “mid-Atlantic” but with a formal definition) that the team plays in (Chiba, Tokyo, Saitama, Tohoku, etc)..

Each team has a “70 man” roster which usually has fewer than 70 players on it. 28 of those players are on the top team’s roster (also known as ichi-gun which literally means “first troop”) Of the 28, only 25 are active for any particular game. The remaining players are on the farm team (also known as ni-gun or “second troop”). Each team has only one farm team.

Most teams also have a handful of players who are not on the “70 man” roster. These players are called “development” or “ikusei” players. You can identify these players by the fact that they have three digit uniform numbers. These players are allowed to play in farm team games but must be signed to the “70 man” roster to play at the top level. A couple teams have enough development players to field an unofficial third team (“san-gun”) which will play corporate or independent league teams. Every year there are a handful of players who “graduate” from being development players – the most famous one is probably Kodai Senga.

Each fall NPB holds a draft for eligible players graduating from high school or college. Players from the corporate and independent leagues can also be drafted if they haven’t previously been drafted in NPB. There are two parts of the draft – a “regular” phase for players who will end up on their team’s “70 man” roster and an “ikusei” draft for development players.

Some Japanese Baseball Card Conventions

Before we get too far down the road, we should mention a couple conventions of Japanese baseball cards.

There is usually the same number of “regular” player cards for each team in each flagship set (one major exception is BBM’s Fusion set). So if a set has 216 cards with no subsets, you’ll know that each team has 18 cards in the set. If the subset is not for the previous year’s statistical leaders or award winners or the All Star lineup, it will also be evenly divided between the 12 teams. Same for insert cards. It’s kind of a nice change of pace from MLB sets with 30 Yankees and 5 Royals.

For baseball card purposes, the players who are taken in a given year’s draft are referred to as rookies the following year. For example all the players who have the “rookie” icon on their 2024 baseball cards were taken in the 2023 draft. This is NOT the same as how NPB treats rookie status which is whether a player has exceeded a certain amount of playing time. This is why the rookie cards for both 2023 “Rookie Of The Year” award winners were in 2021 (since both players were drafted in 2020).

It is extremely rare for there to be baseball cards of college players and unheard of there to be any for high school players. Any card you see of a high school player (or, more likely, a star player from their high school days) on Ebay is likely a “collector’s issue” and not an official card. There are cards for corporate league and independent league players so it IS possible to find “pre-rookie” cards for certain players, but it’s not common.

Because NPB teams treat their farm teams as an extension of the top teams, there are no separate “minor league” team sets for the NPB farm teams or the equivalent of the Topps Pro Debut set.

One major way that NPB card sets differ from MLB sets is that it is extremely rare for a player to be depicted on a team other than the one he is on when the set goes to press. It helps that players move much less frequently in NPB than they do in MLB but I have seen Japanese card companies pull cards from production when a player has been traded.

Japanese Baseball Card Makers

There are currently four companies with a license to produce NPB baseball cards. We’re going to run them down in order of how long they’ve been making cards.

One quick note before we get started. I’m going to mention the sets that each manufacturer typically releases each year but take that with a grain of salt. Sometimes the companies will abruptly change what their releases are. BBM, for example, published boxed sets for the All Star games and the Nippon Series annually for over 20 years before suddenly stopping in 2013.

Calbee

Calbee is a Japanese snack company that has been distributing baseball cards with bags of potato chips since 1973. There was a lot of variety in the size of Calbee’s sets in the early years (and even what constituted a “set”) but things settled down somewhat in the late 90’s where Calbee would issue their “flagship” set in two or three series each year.

Calbee’s sets are generally fairly small, and seem to be shrinking in recent years. Their sets have been in the neighborhood of 160 cards in the past three years. As a result, their sets feature most of the top players in NPB but not as many of the lesser players. Whether or not the set includes many rookie players is very hit or miss as well.

Calbee doesn’t offer any autograph or memorabilia cards with their sets. “Hits” are the “Star” insert cards, especially the parallel versions that feature gold facsimile signatures. It’s also possible to pull a “Lucky Card” which can be mailed to Calbee and exchanged for something. There have been times when the prize has been a special baseball card or cards but frequently it’s simply a card album.

It’s somewhat expensive to get unopened boxes of Calbee cards shipped overseas for the simple reason that the packs of cards are still attached to bags of potato chips! While a typical box including 24 bags of chips that each have a pack of two cards doesn’t weigh a whole lot, it’s larger than you’d think. And it’s very questionable if the expense is worth getting only 48 cards.

BBM

BBM stands for “Baseball Magazine”. BBM’s parent company is Baseball Magazine Sha which has been publishing sports magazines and books since the 1940’s but they didn’t start publishing baseball cards until 1991. They were the first Japanese baseball cards that resembled American cards, with packs containing ten cards and issuing a factory set for their flagship set. There are fewer cards to a pack these days and they haven’t issued a factory set for their flagship set since 1993 but they are unquestionably the largest card company in Japan.

BBM issues a myriad of sets each year but I’m only going to highlight a small subset of them. Their draft pick set – Rookie Edition – usually comes out in late-February and features all the players taken in the previous fall’s draft, both the regular and “ikusei” phases. This is typically where a Japanese player will have his first ever baseball card. The size of the base set is driven by the number of players drafted but is usually around 130. Hits in this set are mostly facsimile signature parallels, some of which are numbered. There are autographed cards available although I think they are mostly redemption cards which may be difficult to exchange from overseas.

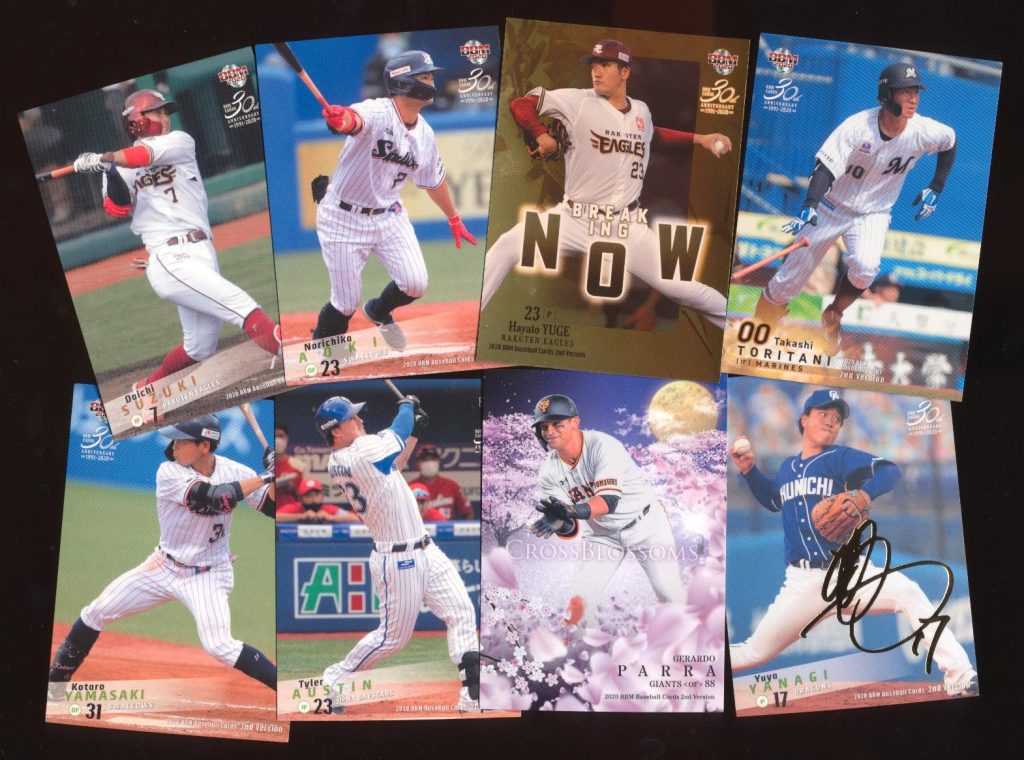

BBM issues their flagship set in three parts – 1st Version comes out in April, 2nd Version comes out in August and Fusion comes out in November. It’s not quite like Topps’ Series One, Two and Update. The design of the “regular” player cards is different between 1st and 2nd Version (although 2nd Version has a “1st Version Update” subset using the same design as the 1st Version cards) while the Fusion set uses yet another card design and is kind of a review of the regular season (although it also has a “1st Version Update” subset). The total size of the base set for the flagship set is around 600 cards although many players have multiple cards. Because of that though, BBM’s flagship sets usually include not just the top stars but most of the regular players for each team. The 1st Version set will also contain cards for all the rookies (i.e. the previous year’s draft picks) from all the team’s “70 man” rosters (so none of the ikusei players). Hits for all three sets include the ubiquitous variety of facsimile signature parallels (including numbered ones) as well as a fair number of autographed cards and a handful of memorabilia cards.

BBM also issues a “comprehensive” team set for each of the 12 teams. What I mean by that is a set that will contain a card for every player on the team’s “70 man” roster or essentially everyone in the organization except the development players. The base sets for these sets contain 81 cards – generally there’s 60-ish “regular” cards for the team’s manager and the players and then 12-15 subset cards to fill out the set. The sets are typically issued between March and July. Hits for the team sets are mostly some special serially numbered insert cards along with autograph and/or memorabilia cards possibly – it depends on the team. For example, the Yomiuri Giants don’t allow their players to do autographs in card sets so the Giants team sets don’t have autographs.

BBM issues a “high end” set called “Genesis” every September. The base set for this set contains 120 cards but no one is interested in this set for the base set. This is the set that BBM has the most autograph and memorabilia cards associated with. Besides the autograph and memorabilia cards, Genesis also has a plethora of numbered parallel cards.

Epoch

Epoch is a Japanese toy company that was founded in the 1950’s but didn’t do their first card set until 2000. That might be stretching things a bit as it was actually a set of stickers that could be pasted into albums. It would be another nine years before they issued their next set which was done in conjunction with what was then called the All Japan Baseball Foundation and is now the National Baseball Promotion Association or OB Club. For the next few years, Epoch would release a handful of sets, usually in partnership with the OB Club and featuring retired (OB) players.

Starting in 2015, Epoch started issuing sets with active players and in 2018 they got serious about competing with BBM, debuting a flagship set along with “comprehensive” team sets for a subset of the teams. They’ve tweaked their offerings somewhat since then though. And as was the case with BBM, I”m only going to highlight a couple of their sets here.

Their flagship set is called NPB and is generally released in May or June. The set had included 432 active players every year between 2018 and 2023, sometimes accompanied by 12 cards of retired players which may or may not have been short-printed. The set has shrunk in size over the past two years, however, with the 2024 set dropping to 336 cards of active players plus the 12 retired players and the 2025 edition further shrinking to 240 cards. Like BBM’s flagship sets, Epoch’s set is large enough to include both the star players and the more average ones. The NPB set will also include cards of all the non-ikusei rookies. Hits from the set include numbered parallels and inserts along with autographed cards.

Epoch issued “comprehensive” team sets in 2018 and 2019 but in 2020 they shifted to team sets that only had 30 or 40 players in them. Originally their team sets were dubbed “Rookies & Stars” but since 2022 they’ve been called “Premier Edition”. Epoch only does these sets for a subset of the teams, although they appear to be adding more teams each year. The sets will contain most of the starters for the team (including the stars obviously) along with (again) the team’s rookie class which may include “ikusei” players depending on the team. The hits in the boxes include a variety of serially numbered parallels and inserts along with autograph cards.

Topps

While Topps has been publishing baseball cards in the US for over 70 years, they are relatively new to the NPB market. They announced their NPB license at the beginning of October of 2021 and put their first set out two months later. Because they’re so new it’s difficult to say for sure what their usual sets are.

They’ve issued a 216 card flagship set each year that uses a similar (but not necessarily identical) design as their MLB flagship set. The set has more rookie cards than Calbee generally does but has never contained the year’s entire rookie class. Hits have generally been a plethora of different parallels but they’ve recently started adding autographs. For a while, the autographed cards were not for current NPB players but instead for both current and retired Japanese MLB players such as Ichiro, Hideki Matsui and Shohei Ohtani (although the players are depicted in their NPB uniforms). They have started adding current NPB players more recently.

Topps has also issued a Chrome set each year. The first two iterations of this set were essentially a “Chrome” parallel of the flagship set although since then the set’s been different – a new checklist containing some different players and all new photos. Hits again are parallels and autograph cards.

Topps also issued NPB versions of their Bowman set in 2022 and 2023; their 206 set in 2023 and 2024; their Stadium Club set in 2024 and 2025; and their Finest set in 2025. They’ve issued four sets a year since 2022 with only two in their initial year.

So far, Topps has issued all of their NPB sets via packs.

Both Epoch and Topps offer on demand cards for NPB. Epoch’s are called Epoch One while Topps uses the Topps Now moniker for their Japanese cards as well. It is extremely difficult to get these from overseas as neither company will ship these cards outside the country.

What I’ve listed here aren’t all the sets that these manufacturers put out but they’re most of the perennial ones and probably the most straightforward sets. There are cards besides the ones from these companies but they are much more difficult to find from overseas. Most if not all of the teams issue cards through their fan clubs and often give cards away with meals at the ballpark. Like in the US, there may be cards given away with food products at stores and sometimes those cards are done in conjunction with BBM or Epoch.

There’s also usually some collectible card game (CCG) set available although the manufacturer seems to change every few years. Bushiroad issued a CCG called DreamOrder in 2024 and 2025 but I’m not sure if they’re continuing this year. Bandai is apparently issuing a CCG soon called “Fanstars League”. Bandai had previously issued a CCG called “Owners League” in the 2010’s and both Takara and Konami have issued ones in the past.