by Taein Chun

Gwangju Jeil High School, known as Gwangju Ilgo, is located in Gwangju Metropolitan City in the southwestern region of Korea and is the school that has produced the greatest number of Major League Baseball players in the country. In the early 2000s, Jae Weong[c1] Seo of the New York Mets and Los Angeles Dodgers, Byung-hyun Kim of the Arizona Diamondbacks and Boston Red Sox, and Hee-seop Choi of the Chicago Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers reached the MLB stage one after another. Although the three played for different teams, they shared the distinction of being Gwangju Ilgo alumni, and they were called the Gwangju Ilgo Trio as they demonstrated the international competitiveness of Korean baseball. In the mid-2010s, Jung-ho Kang of the Pittsburgh Pirates became the first KBO hitter to move directly to MLB, opening a new path. In 2025, Kim Sung Joon signed with the Texas Rangers as the next emerging player. A total of five Gwangju Ilgo alumni have signed with MLB organizations, the most among Korean high schools. The school also ranks among the highest domestically for producing KBO league players, with 119 Gwangju Ilgo graduates appearing in first division games as of 2024.

1924, The Spark of Anti-Japanese Spirit That Began on a Baseball Field

Baseball at Gwangju Ilgo was not simply a sport from the beginning but a symbol of resistance and pride. The baseball team, founded in 1923, is one of the oldest in Korean high school baseball. In June of the following year, the baseball team of what was then Gwangju Higher Common School defeated a Japanese select team called Star by a score of 1 to 0 in an exhibition match. In colonial Korea, the victory of Korean students over a Japanese team was a rare moment of national joy. The field filled with cheers as players and spectators celebrated together, shouting manse. The atmosphere changed abruptly when Star’s manager, Ando Susumu, stormed onto the field in protest, causing chaos as spectators and players clashed, and the Japanese cheering section also joined. Japanese police intervened, and Ando claimed that he had been struck in the forehead by a spike, identifying nine Gwangju players as the attackers. They were immediately detained. Outraged students launched a schoolwide strike that lasted three months. This incident marked the first organized student protest against colonial rule and served as a catalyst for the 1929 Gwangju Student Independence Movement. A monument to the movement still stands on the school grounds. Before national tournaments, Gwangju Ilgo players bow their heads before the monument, renewing their resolve never to give up. This tradition grew into the team’s philosophy, and their strong fundamentals and concentration reflect this spirit.

1980, The Silent Time That Baseball in Gwangju Protected

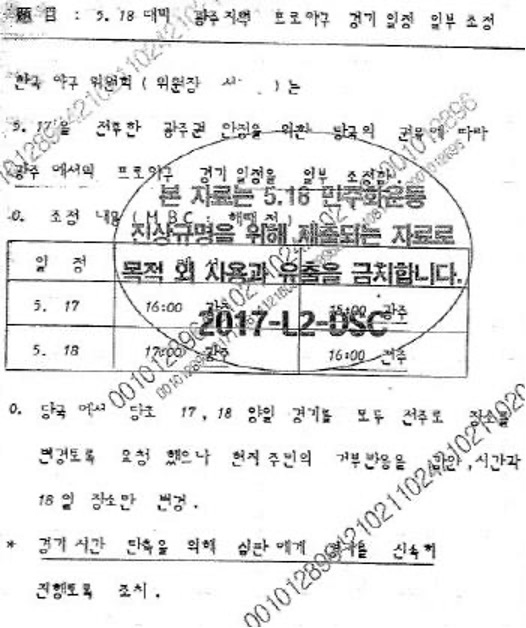

If Gwangju Ilgo in the 1920s contained an anti-Japanese consciousness, then its baseball in the 1980s walked alongside the era of democratization. In the spring of 1980, citizen protests for democracy against the military regime took place in Gwangju. This event, which is called the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, became a major turning point in modern Korean history. At the time, some Haitai Tigers players were still students, and that generation experienced up close the confusion and sacrifice that engulfed the entire city. The atmosphere of that time, when soldiers fired guns at citizens, left a deep impression on the team’s attitude. The more their home city, Gwangju, fell into turmoil, the more the Haitai Tigers players banded together and comforted the hearts of citizens with strong teamwork and hustle play. Former Haitai Tigers player Chae-geun Jang was in Gwangju on May 18. He remembers it as follows. “There were helicopters, soldiers, and the sound of gunfire. At night, we turned off the lights and stayed quiet. I even remember seeing bodies on the street.” Jang said that when May came, fans and players naturally spoke about those memories. For several years afterward, due to political instability, home games were not held in Gwangju around May 18. The government, concerned about large crowds in the Gwangju area around the May 18 memorial, requested that the Korea Baseball Organization adjust its schedule. As a result, throughout the 1980s, the Haitai Tigers had to play games in other regions around May 18. Only in 2000, the twentieth anniversary of the democratization movement, was a home game in Gwangju finally held again on May 18.

Even so, Haitai did not waver. Beginning with their first Korean Series championship in 1983, they went on to win four consecutive titles from 1986 to 1989, five championships in the 1980s, and four more in the 1990s, establishing what came to be called the Haitai dynasty. At the center of this dynasty were core players from Gwangju Ilgo such as Dong-yeol Sun, Lee[c1] Kang-chul Lee, and Jong-beom Lee. With solid fundamentals and concentration as their weapons, they led the team and helped raise the overall standard of Korean professional baseball. In this way, baseball in Gwangju took root as a source of regional pride.

The Characteristics and Development Environment of the Gwangju Region

The intense baseball passion in Gwangju began during the golden age of the Haitai Tigers in the 1980s and 1990s. Haitai’s repeated championships became a source of pride for the region, and baseball took firm root as Gwangju’s representative sport. From this period on, parents increasingly tried to raise their children as baseball players, and Gwangju came to be recognized as a city where one could succeed through baseball. Gwangju is a mid-sized city with a population of around 1.4 million. In general, in a city of this size in Korea, maintaining elementary, middle, and high school baseball teams in a stable way is difficult, but Gwangju is an exception. Baseball teams at schools across the region operate on a steady basis, and youth baseball teams are also active. This environment has led to a youth baseball culture in which many players set Gwangju Ilgo as their target school. In addition to Gwangju Ilgo, there are other prestigious baseball schools in the city,such as Jinheung High School and Dongseong High School, the former Gwangju Commercial High School. These schools also have experience winning national tournaments, but in terms of the concentration of player resources and students who hope to advance, Gwangju Ilgo stands at the top. Former KBO technical committee chair In-sik Kim evaluated the situation by saying that while Busan divides its talent between Kyungnam High and Busan High, in Gwangju, the player pool is concentrated at Gwangju Ilgo. Gwangju Ilgo recruits players not only from Gwangju but from all across South Jeolla Province, and promising prospects from middle schools in the area, such as Mudeung Middle School and Chungjang Middle School, as well as nearby cities including Naju and Suncheon, also join the program. As a result, internal competition becomes very intense, and players who pass through that competition show a high level of fundamentals, physical conditioning, and game focus.

Industrialization and economic growth in Korea have taken place mainly in the capital region, meaning Seoul and Gyeonggi, and in the Gyeongsang region, including Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, and the surrounding provinces. In contrast, the Honam region has had a relatively weaker economic base. Because of this, baseball has been seen as a realistic career path through which one can raise social status by effort and performance. In such an environment, when parents made decisions about their children’s future, they often favored sports, especially baseball. This culture has continued across generations up to the present. Gwangju Ilgo still supports the roots of Korean baseball today. Even as generations change, the philosophy of valuing fundamentals and mental strength has not changed. From its founding in 1923 to MLB advancement in 2025, Gwangju Ilgo has been both the place that has created the present of Korean baseball over a century and the site where its future is being prepared.