by Thomas Love Seagull

A recent poll for a TV special saw more than 50,000 people in Japan vote for their favorite retired baseball players. 20 players emerged from a pool of 9,000. Yes, they could only vote for players who are no longer active, so you won’t see Shohei Ohtani or other current stars on this list. Which is probably smart because I’m sure Ohtani would win by default. There are, however, players who were beloved but not necessarily brilliant, and foreign stars who found success after coming to NPB. Unsurprisingly, the list leans heavily towards the past 30 years, with a few legends thrown in for good measure.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be profiling each of these players. Some of these players I know only a little about, so this will be as much a journey for me as, hopefully, it will be for you. It’ll be a mix of history, stats, and whatever interesting stories I can dig up.

For now, have a look at the list below and see how the public ranked them. I’ve included the years they played in NPB in parentheses.

20. Alex Ramirez (2001-2013); 19. Yoshinobu Takahashi (1998-2015); 18. Warren Cromartie (1984-1990), 17. Takashi Toritani (2004-2021); 16. Suguru Egawa (1979-1987); 15. Katsuya Nomura (1954-1980); 14. Tatsunori Hara (1981-1995); 13. Kazuhiro Kiyohara (1985-2008); 12. Masayuki Kakefu (1974-1988); 11. Masumi Kuwata (1986-2006); 10. Atsuya Furuta (1990-2007); 9. Randy Bass (1983-1988); 8. Daisuke Matsuzaka (1999-2006, 2015-2016, 2018-2019, 2021); 7. Tsuyoshi Shinjo (1991-2000, 2004-2006); 6. Hiromitsu Ochiai (1979-1998); 5. Hideo Nomo (1990-1994); 4. Hideki Matsui (1993-2002); 3. Shigeo Nagashima (1958-1974); 2. Sadaharu Oh (1958-1980); 1. Ichiro Suzuki (1992-2000).

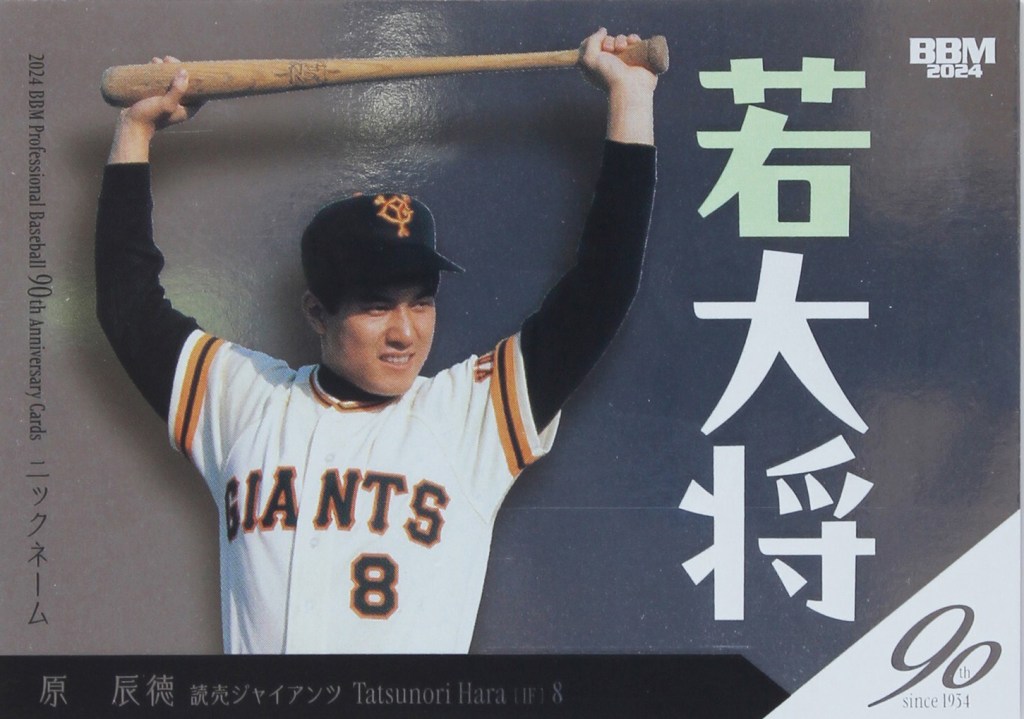

Japan’s Favorite Players: No. 14, Tatsunori Hara

The man asked to follow Sadaharu Oh and Shigeo Nagashima

For a long time, Japanese baseball kept asking the same question.

No, not who is the next great player, but something much harder, and much crueler:

Who comes after giants?

Sadaharu Oh had just finished rewriting what power meant. Shigeo Nagashima had already become something more than a ballplayer—he was posture, gesture, spirit, shorthand for what it meant to be Japanese. Together, they were not simply stars but a system. ON was the Yomiuri Giants’ and, by extension, Japanese baseball’s center of gravity.

When they were gone, pro yakyu didn’t just need a hitter.

It needed a successor.

So when Tatsunori Hara arrived, the nation decided, almost instantly, that he would be the one.

Hara had been trained for baseball since he was three years old by his father, Mitsugu, a famously strict high-school and college coach. He starred as a third baseman at Tokai University Sagami High School, then at Tokai University itself, where he won two Triple Crowns in the Metropolitan League and became the most polished amateur slugger in the country. He helped Japan win bronze at the 1980 Amateur World Series. He hit. He smiled. He looked the part. In his senior year of university, he further fueled expectations of being the second coming of Nagashima by hitting three home runs in a single game at the Meiji Jingu Baseball Tournament.

Most importantly, he wanted to be a Giant.

In the fall of 1980, the Yomiuri Giants were in turmoil. Nagashima had been dismissed as manager. Oh had retired. Fans protested. Newspapers, owned by the Yomiuri group, were boycotted. The franchise needed stability, and it needed a new face.

At the draft, four teams competed for Hara. New Giants manager Motoshi Fujita drew the winning lot.

People inside the Yomiuri building reportedly embraced. Newspapers ran banner headlines speculating whether Hara might even inherit Nagashima’s sacred number 3. He didn’t, but number 8 would soon become just as recognizable.

From the moment he signed, Hara was not treated like a rookie. He was treated like a hero. Magazines followed him through spring camp, staged photo shoots, even placed him on horseback in the mountains. A cheer song, Our Beloved Big Brother Tatsunori*, was released on vinyl before he had played a professional game. Teenage girls wrote in to say they had switched allegiances to the Giants because of him. More than ten thousand fans showed up just to watch him practice. The team expanded its public-relations staff to manage the crowds.

*It’s roughly “the big brother everyone admired” but I’m sure someone else has a better translation.

With an established third baseman already in place, Hara prepared to play second and spoke earnestly about becoming something new, a large infielder who could hit home runs from a position that did not yet ask for them. He took notes obsessively, writing down how pitchers attacked him, what he swung at, what he should have done differently. When coaches suggested rest when he was sick, or when he was exhausted, he refused. “I’m fine,” he insisted. “I can do it.”

The criticism arrived anyway. Nine games into his career, despite hitting safely in six straight, the phrase appeared: weak in the clutch. It would follow him for the rest of his playing life.

But his first professional season in 1981 was, by any rational measure, outstanding. He hit .268 with 22 home runs, won Rookie of the Year, and helped lead the Giants to a league title and Japan Series championship. He hit a walk-off homer in April that sent fans spilling onto the field. He was promoted relentlessly on television, in magazines, and in advertisements. Marriage proposals arrived at the team office. Film studios called. He was voted Japan’s top male symbol of the year.

The Giants had found their prince.

And almost immediately, people began asking why he wasn’t a king.

Hara followed his rookie year with equally impressive performances. Thirty home runs became routine. In 1983, he hit .302 with 32 homers, led the league in RBIs, won MVP, and captured a batting Triple Crown of his own kind: average, power, authority. It should have been the coronation for the new king.

Instead, it became the high-water mark.

He never again led the league in a major offensive category. He was always near the top, productive and present, but rarely first. Other sluggers outpaced him: Masayuki Kakefu, Hiromitsu Ochiai, Randy Bass. He made the Best Nine and won Golden Gloves but that wasn’t enough. And because Hara wore the Giants’ uniform, and because he was supposed to be more than merely excellent, closeness to greatness was interpreted as a failure.

The criticism followed a familiar script: he wasn’t clutch enough; he should have hit forty home runs; he smiled too much. The expectations had been inherited, not earned and, therefore, impossible to satisfy.

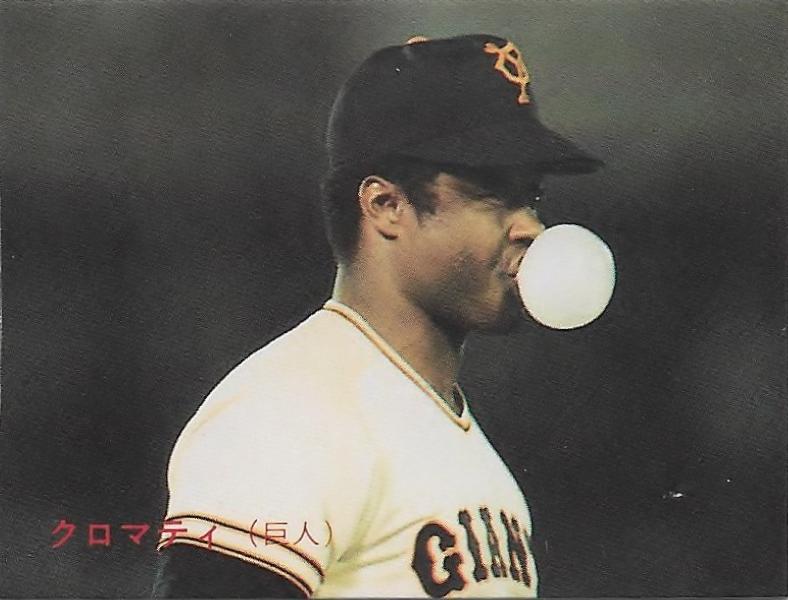

No one captured the tension better than Warren Cromartie, Hara’s American teammate in the 1980s. In his book Slugging It Out in Japan with Robert Whiting, Cromartie described Hara as the Giants’ “glamour boy,” endlessly promoted, endlessly photographed, endlessly scrutinized.

Hara, according to Cromartie, endured constant extra practice, endless instruction, and relentless attention from coaches who believed that precision mattered more than instinct. He complied with everything. If told to sleep in the batting cage, Cromartie joked, Hara would ask whether he needed a futon.

Cromartie believed Hara was overcoached, overexposed, and ultimately constrained by the very system that needed him so badly. Hara wanted to swing freely. He wanted to simplify. But the Giants, like Japanese baseball itself, wanted obedience and control.

And Hara, above all, wanted to be worthy of the uniform.

That desire reached its breaking point on September 24, 1986.

The Giants were chasing Hiroshima for the pennant. Hara had already hit a career-high 36 home runs that season. During a game in August, he had injured his left wrist in the field. Painkillers allowed him to keep playing, but he later said he could only swing at sixty or seventy percent.

In the ninth inning, with two outs and a runner on base, Hara came to the plate. On the mound for the Carp was Tsunemi Tsuda*, the Fiery Closer, pitching with full force, as he always did.

*Tsuda tragically died in 1993 at the age of 32 from a brain tumor. He was inducted into the Japanese Hall of Fame in 2012.

Hara knew holding back was safer. But he also knew restraint was unacceptable for a Giant.

Tsuda came in hard. Hara swung as hard as he could. The ball went foul. There was a sharp cracking sound at contact, and Hara knew immediately.

The bone in his wrist was broken.

Years later, Hara said that was the swing that ended him as a hitter*. He said he never truly found the same feeling again. And yet, he never regretted it.

*He hit .300 with 30 home runs for two consecutive years in 1987 and 1988, but if the man himself says he was never quite the same, he was never quite the same.

“Even now,” Hara said, “I think that swing was my best one.”

That sentence tells you everything about Tatsunori Hara.

After that moment, even if he was never quite the same, he was never quite absent. He moved to the outfield. He continued to hit 20-plus home runs year after year. He adapted. He endured.

And in 1989, when the Giants needed him one more time, he delivered the hit that would define his reputation more than any criticism ever could.

In the Japan Series against Kintetsu, Hara went 18 straight at-bats without a hit. He was struggling. He was hurting. He was, once again, being questioned.

In Game 5, with Yomiuri trailing the series 3 games to 1, the Giants loaded the bases. Kintetsu’s Masato Yoshii intentionally walked Cromartie to face Hara instead.

Hara hit a grand slam.

The Giants won the next three games and the championship. Although Hara struggled throughout the series and finished with only two hits, both were home runs—the grand slam in Game 5 and a two-run homer in Game 7—and he drove in six runs in total, surpassing even series MVP Norihiro Komada* in RBIs.

*Komada was the first player in NPB history to hit a grand slam in his first plate appearance. He ended his career with 13 grand slams and one of the coolest nicknames ever, “Mr. Bases Loaded”.

The decline came quietly. Achilles tendon injuries mounted. Playing time shrank. By the mid-1990s, the Giants were entering a new era, one of Hideki Matsui, free-agent stars, and a different kind of power. Hara was not only no longer the future: sometimes he was no longer even the present.

And yet, something curious happened.

As expectations fell, affection deepened. Older fans who had lived through the ON era often measured Hara against memory and found him lacking. Younger fans, those who had never seen Nagashima play, who knew Oh only through numbers, saw something else. They saw the cleanup hitter who took the licks meant for giants. The star who was told, year after year, that thirty home runs was not enough. The man who kept getting back up even after injuries knocked him out.

In a role that demanded perfection, Hara survived by being human. His imperfections made him accessible. When he began to fade, the applause grew louder. Not because he was still great, but because he was still there, because he had persevered.

In 1995, Hara retired after fifteen seasons. In his final game, he hit one last home run. At the ceremony afterward, he spoke about the Giants’ cleanup hitter as a sacred role, one that no one could claim lightly.

“My dream ends today,” he said.

“But my dream has a continuation.”

That continuation arrived in the form of authority.

As a manager, Hara won nine league titles, three Japan Series championships, and led Japan to victory at the 2009 World Baseball Classic. The system that never fully trusted him as a player eventually handed him everything.

Even then, the burden of symbolism did not lift. In 2012, long after his playing days had ended but in the midst of his second managerial stint, reports surfaced of an extramarital affair from his playing days and of hush money paid years later under pressure from men later identified as having ties to organized crime: the yakuza. Hara admitted to the core facts and apologized publicly. The courts ultimately ruled that the reporting was substantially true. It was messy and uncomfortable.

In the end, Tatsunori Hara did not become Nagashima. He did not become Oh. He became something else: the man who carried the weight between eras.

To some, he will always be the prince who never became a king. To others, the superstar who was never free. But perhaps the truest version is this: Tatsunori Hara was Japanese baseball’s most successful act of containment. Loved loudly, corrected endlessly, and trusted completely. He did not break under expectation. He lived inside it, smiling for the cameras, swinging when allowed, and carrying the quiet burden of being exactly what Japan wanted him to be.

History is cruel to its heirs.

Thomas Love Seagull’s work can be found on his Substack Baseball in Japan