by Thomas Love Seagull

A recent poll for a TV special saw more than 50,000 people in Japan vote for their favorite retired baseball players. 20 players emerged from a pool of 9,000. Yes, they could only vote for players who are no longer active, so you won’t see Shohei Ohtani or other current stars on this list. Which is probably smart because I’m sure Ohtani would win by default. There are, however, players who were beloved but not necessarily brilliant, and foreign stars who found success after coming to NPB. Unsurprisingly, the list leans heavily towards the past 30 years, with a few legends thrown in for good measure.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be profiling each of these players. Some of these players I know only a little about, so this will be as much a journey for me as, hopefully, it will be for you. It’ll be a mix of history, stats, and whatever interesting stories I can dig up.

For now, have a look at the list below and see how the public ranked them. I’ve included the years they played in NPB in parentheses.

20. Alex Ramirez (2001-2013); 19. Yoshinobu Takahashi (1998-2015); 18. Warren Cromartie (1984-1990), 17. Takahashi Toritani (2004-2021; 16. Suguru Egawa (1979-1987); 15. Katsuya Nomura (1954-1980); 14. Tatsunori Hara (1981-1995); 13. Kazuhiro Kiyohara (1985-2008); 12. Masayuki Kakefu (1974-1988); 11. Masumi Kuwata (1986-2006); 10. Atsuya Furuta (1990-2007); 9. Randy Bass (1983-1988); 8. Daisuke Matsuzaka (1999-2006, 2015-2016, 2018-2019, 2021); 7. Tsuyoshi Shinjo (1991-2000, 2004-2006); 6. Hiromitsu Ochiai (1979-1998); 5. Hideo Nomo (1990-1994); 4. Hideki Matsui (1993-2002); 3. Shigeo Nagashima (1958-1974); 2. Sadaharu Oh (1958-1980); 1. Ichiro Suzuki (1992-2000).

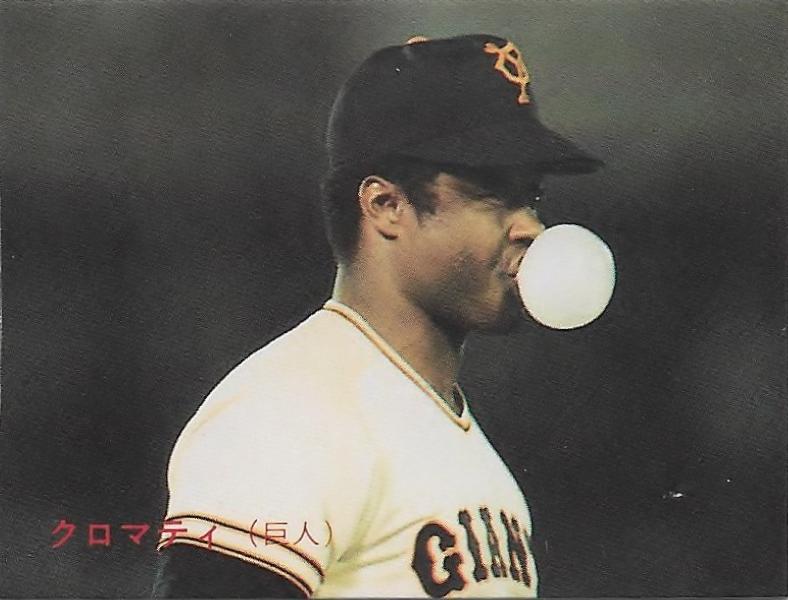

No. 18 Warren Cromartie

He could have hit .400. Instead, he kept playing.

By 1989, Japanese baseball was louder than ever. The consumption tax had just arrived, ticket prices rose across the league, and the Yomiuri Giants—charging more than any team in the country—still packed the Tokyo Dome nightly. Nearly every Giants game aired live in prime time. And at the center of all of it stood Warren Cromartie.

This was not where he had expected to be. He had come to Japan planning to stay a few years, then leave baseball behind to become a professional drummer. He said this every spring. Yet each year, he stayed.

In the season when he was most convinced he was finished, he played as if baseball were refusing to let him go.

By August of 1989, Warren Cromartie was hitting .400, and everyone knew exactly what that meant. Nobody had ever hit .400 in Japanese baseball.

They told him to sit down. Even his manager, Motoshi Fujita, offered to keep him out of the lineup.

He had already reached the required plate appearances. If he stepped away now, the .400 would belong to him forever.

Cromartie did not stop.

He kept his name in the lineup for the Yomiuri Giants because the Giants were winning, because the season was still alive, and because baseball players are trained—almost against their own interest—to believe that the game comes before the number. The average slipped. .399. .395. .390. With every decimal, the tension grew. Japan had never seen a .400 hitter. It wanted one badly.

By the end of the season, the number settled at .378.

Cromartie won the batting title. He led the league in on-base percentage. He was named Central League MVP on a championship team. His .378 remains the highest batting average in the long, decorated history of the Yomiuri Giants.

He recorded season batting averages of .360 or higher twice (1986 and 1989), a feat achieved by only two other players: Ichiro (1994, 2000) and Hiromitsu Ochiai* (1985, 1986).

*Ochiai won the Triple Crown (leading the league in batting average, home runs, and RBIs) both seasons (and also in 1982) but was traded by Lotte to Chunichi due to his unhappiness with the direction Lotte’s management was taking.

This was not a story that began in 1989, or even in Japan. But it was a story that only makes sense there: inside the Tokyo Dome, under the weight of expectation, with a season that dared him to choose between baseball immortality and the game itself.

He chose the game.

Warren Cromartie was never a baseball nobody. If anything, he arrived in Japan because he had been almost somebody for a very long time.

In Montreal in the late 1970s, the Expos unveiled an outfield that felt like the future: Andre Dawson in center, Ellis Valentine in right, and Cromartie drifting between them. They were young, fast, and talented enough to make the Expos relevant for the first time. Cromartie hit close to .300, scored runs, played every day, and helped push Montreal into repeated pennant races that ended just short.

That became the pattern. Cromartie was productive but unsettled, as he was shifted between left field, right field, and first base, good enough to keep his job, never quite secure enough to own it. He played on winning teams, reached the postseason once, and even stood in the on-deck circle when the Expos’ season ended in the 1981 NLCS.

By 1983, with injuries mounting and his role shrinking, Cromartie became a free agent. He was thirty years old, far too young to be finished.

He expected to sign with the highest bidder. He did not expect the San Francisco Giants to be outbid at the last minute by the ones from Tokyo.

Cromartie did not arrive in Tokyo as a curiosity. He arrived as a declaration. At the time, foreign players in Japan were often veterans at the end of their careers. Cromartie was different. He was still in his prime. The Giants signed him not as a stopgap but as a centerpiece, and Sadaharu Oh, baseball’s Home Run King, became his manager.

Oh noticed something immediately. There was a hitch in Cromartie’s swing. During batting practice, Oh made him hit with a book tucked under his elbow to smooth it out. Cromartie listened.

He hit, and hit, and hit some more.

Thirty-five home runs in his first season. Game-winning RBIs. A broad, infectious joy that spread throughout Korakuen Stadium and, later, the Tokyo Dome. Cromartie chewed gum constantly, blew bubbles, and celebrated big hits with a now-famous banzai salute toward the outfield stands. Years later, he explained that it wasn’t choreographed or taught but was simply something he saw on TV and in Japanese celebrations and loved. It looked fun so he made it his.

That joy mattered. Cromartie later said his success in Japan came not from changing who he was as a hitter, but from learning how to live there. Veteran foreign players, like Reggie Smith and the Lee brothers, taught him how to ride trains, eat the food, respect the routines, and understand the culture.

Even his bond with Oh went beyond baseball. When Cromartie’s second son was born, he named him Cody Oh Cromartie.

Cromartie’s Japanese career was not smooth. He was emotional, proud, sometimes combustible. He fought pitchers who he believed disrespected him. One infamous punch thrown in 1987 became a permanent part of his highlight reel and, later, a permanent regret.

The drama began when Chunichi’s Masami Miyashita hit Cromartie with a pitch in the back. Enraged, Cromartie charged the mound, gesturing for Miyashita to take off his hat and apologize, as is customary in Japan. When Miyashita refused, Cromartie landed a powerful right hook to Miyashita’s left jaw, sparking a wild brawl that saw both teams involved in a chaotic fight.

The altercation became the talk of the sports world, overshadowing a historic achievement that same day by Hiroshima’s Sachio Kinugasa. Kinugasa had tied Lou Gehrig’s record for 2,130 consecutive games played, but the next day’s newspapers were dominated by the brawl, relegating Kinugasa’s feat to an afterthought*.

*The incident was so famous that when he started working after his retirement, Miyashita included a photo of him being punched by Cromartie on his business card.

After the incident, Cromartie’s mother, who was in Japan for the first time to watch him play, was furious after seeing the scene on TV, and for a week, she wouldn’t speak to him.

Years later, Cromartie and Miyashita crossed paths at the Tokyo Dome. Miyashita approached Cromartie, who immediately apologized for the punch. The two began to rebuild their relationship, with Miyashita insisting that it was he who should be apologizing.

The defining moment, though, came a year earlier, with the Giants locked in a fierce pennant race.

A pitch struck Cromartie in the head. He collapsed. He was taken to the hospital. The season—and perhaps something worse—felt like it might be over.

The next day, Cromartie escaped the hospital and went to the ballpark.

He did not start. He waited. When he was called upon as a pinch hitter, the bases were loaded. The stadium held its breath.

He hit a grand slam.

When he crossed the plate, he wept and embraced Sadaharu Oh. It was not bravery. It was stubbornness, belief, and love for the game colliding all at once. The Giants would not win the title that year, but the image lasted. Some moments do not require championships to become permanent memories.

Which brings everything back to 1989.

Cromartie announced, before the season began, that it would be his last. He had a music career to get to, after all. That season, he changed the way he hit. He stopped trying to force power, spread the ball across the field, and accepted fewer home runs in exchange for constant pressure.

Then he started hitting like a man unwilling to leave. .470 in May. .396 deep into June. Over .400 even after qualifying for the batting title.

People begged him to sit. If he stopped playing, .400 would stand.

Cromartie remembered that conversation clearly. “If it had been the final couple of weeks, maybe I would have,” he said later. “But it was still August. I couldn’t say I wanted to sit just for my own record. I was playing for the Giants.”

There was also history layered quietly beneath the numbers. Cromartie became the first Central League MVP of the Heisei era, and in a coincidence that felt like a signal, both leagues named foreign players as MVPs that year—Cromartie in the Central League, Ralph Bryant of the Kintetsu Buffaloes in the Pacific. It was the first time that had ever happened, a subtle acknowledgment that maybe Japanese baseball was changing, and that its biggest moments were no longer reserved only for its native sons*.

*Although the treatment of Randy Bass during the same time frame would suggest otherwise.

The average fell. The number slipped away. The season became legendary anyway.

MVP. Batting champion. Highest average in Giants history. A Japan Series title, sealed with a home run in the deciding game against Bryant’s Buffaloes.

By the time Cromartie left the Giants, the record was unmistakable. In 779 games, he hit .321 with 171 home runs and 558 RBIs. Fans had adored him. Among foreign players in franchise history, no one has surpassed him in average, power, production, or longevity.

But Warren Cromartie matters because baseball is not built only on the players who set records. It is built on the ones who stand at the edge of history and keep playing anyway.

Years later, when asked if he had regrets beyond that single punch thrown in anger, Cromartie didn’t hesitate. He said he would sign the same Giants contract again. He would make the same choice again.

Many foreign players have passed through Japanese baseball, but Warren Cromartie was absorbed into it.

Thomas Love Seagull’s work can be found on his Substack Baseball in Japan