by Steven Wisensale

We have moved the Nichibei Yakyu series to Mondays to make room for a new series of articles by Thomas Love Seagull debuting this Wednesday, January 14.

Every Monday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Steven Wisensale tells us about the New York Giants trip toJapan in 1953.

On the morning of June 29, 1953, readers of the Globe Gazette in Mason City, Iowa, were greeted by a headline on page 13: “New York Giants Invited to Tour Japan This Fall.”

The Associated Press in Tokyo reported that Shoji Yasuda, president of the Yomiuri Shimbun, had formally invited Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, to bring his team to Japan for a goodwill tour after the season. The tour was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Commodore Matthew Perry’s arrival in Japan in 1853, when he forced the isolated nation’s ports to open to the world.

An excited Stoneham quickly sought and was given approval for the trip from the US State Department, the Defense Department, and the US Embassy in Tokyo. The tour was also endorsed by Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick. However, two hurdles remained for Stoneham: He needed his fellow owners to suspend the rule that prohibited more than three members of a major-league team from playing in postseason exhibition games. And at least 15 Giants on the major-league roster had to vote yes for the tour.

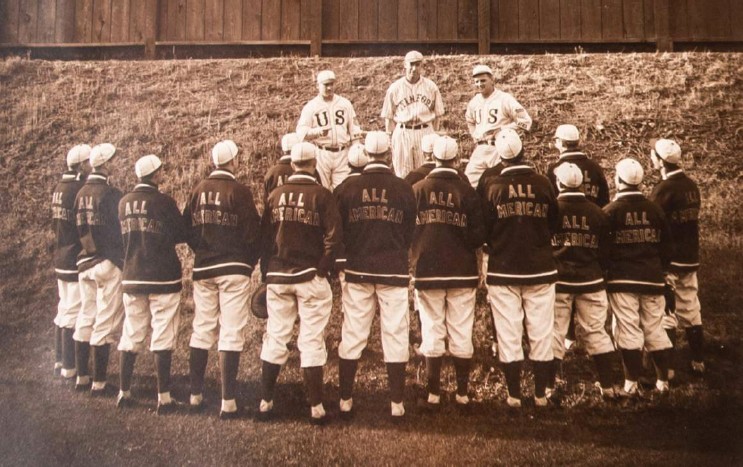

With respect to the first hurdle, previous postseason tours had consisted primarily of major-league allstars, not complete teams. The 1953 Giants, however, became trailblazers as the first squad to tour Japan as a complete major-league team. The second rule was a requirement set forth by the Japanese sponsors of the tour. They wanted their Japanese players to compete against top-quality major leaguers.

WAIVER IS GRANTED

The waiver Stoneham sought was granted by team owners on July 12 when they gathered in Cincinnati for the All-Star Game “We will now proceed with our plans for the goodwill tour,” said an upbeat Stoneham.

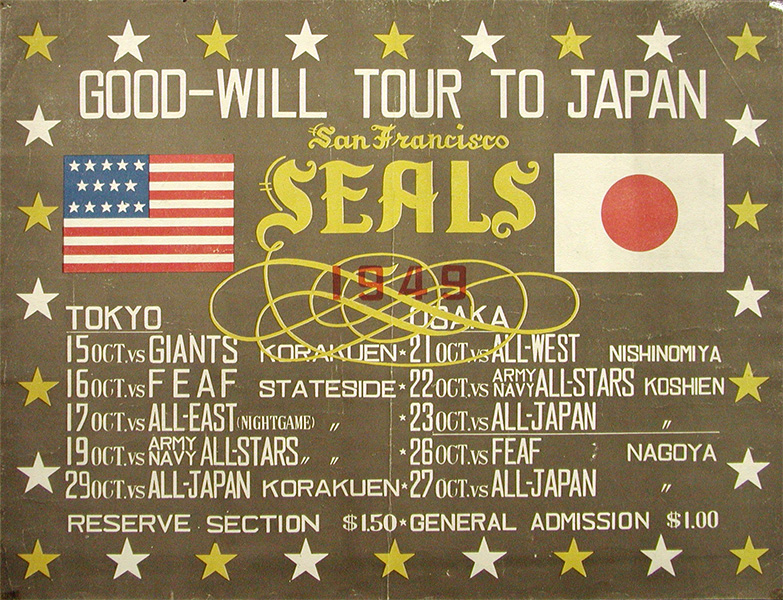

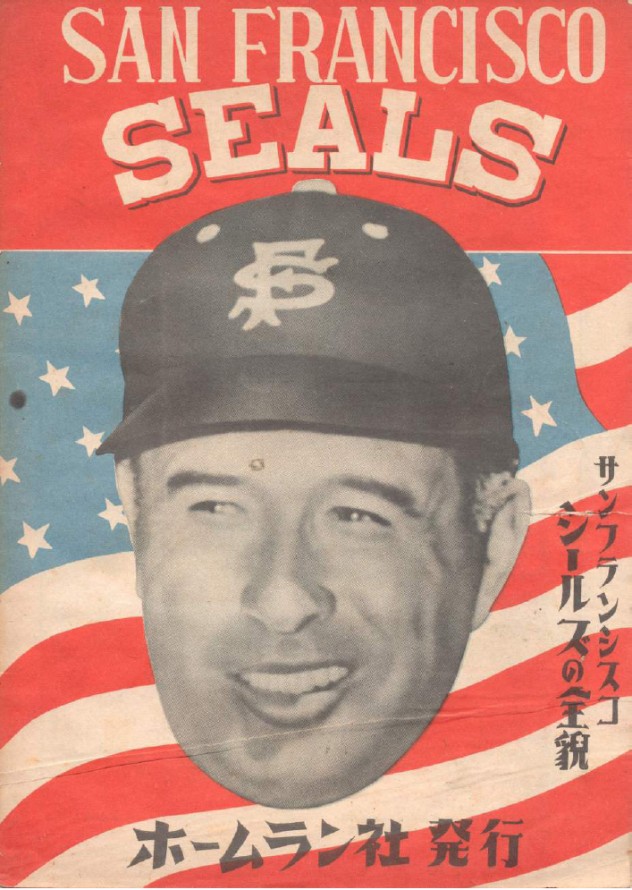

Another person who was extremely happy with the owners’ decision to support the Giants’ tour of Japan was Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada. Harada was a US Army officer serving with the American occupation force in postwar Japan and an adviser to the Yomiuri Giants. One of his tasks was to restore morale among the Japanese people through sports, particularly baseball. It was Harada who suggested to General Douglas MacArthur that the San Francisco Seals be invited to Japan for a goodwill tour in 1949. Working closely with Lefty O’Doul, Harada coordinated the tour, which MacArthur later declared was “the greatest piece of diplomacy ever,” adding, “all the diplomats put together would not have been able to do this.” O’Doul would play a central role in 1953 by assisting Harada in coordinating the Giants’ tour.

After the owners granted approval, Harada flew to Honolulu, where he met with city officials and baseball executives to share the news that Hawaii would host two exhibition games during the team’s layover on their journey to Japan.

At a press conference on July 18 in Honolulu, Harada explained why the Giants were chosen for the tour: They were the oldest team in major-league baseball, and they had Black players. A Honolulu sports- writer observed: “The presence of colored stars on the team will help show the people of Japan democracy at work and point out to them that all the people in the United States are treated equally.”

Harada’s statement was not exactly accurate. First, while the Giants were one of the oldest professional teams, they were not the oldest. Five other teams preceded them: the Braves, Cubs, Cardinals, Pirates, and Reds. And Harada’s statements regarding racial diversity and “equality for all” were misleading. By the end of the 1953 season only eight of the 16 major-league clubs were integrated. Jim Crow laws were firmly in place in at least 17 states and the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ended segregated schooling, was a year away. However, Harada was correct in emphasizing the visual impact an integrated baseball team on the field could have on fans, and society as a whole, as Jackie Robinson taught America in 1947.

The Giants also were selected because of Harada’s close relationship with Lefty O’Doul and O’Doul’s strong connection to Horace Stoneham, which began in 1928 when Lefty played for the Giants. At one point Stoneham even considered hiring O’Doul as his manager. Harada, who was bilingual, lived in Santa Maria, California, where, in the spring of 1953, he arranged for the Yomiuri Giants to hold their spring-training camp. Working closely together, Harada and O’Doul (with Stoneham’s approval) scheduled an exhibition game in Santa Maria between the New York Giants and their Tokyo namesake. O’Doul introduced Harada to Stoneham, and the seeds for the Japan tour were planted.

A CLUBHOUSE VOTE

The one remaining hurdle was a positive vote by at least 15 Giants. Prior to voting, they were told that the tour would take place from mid-October to mid-November. They would play two games in Hawaii on their way to Japan, 14 games in Japan, and a few games in Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam before returning home. They understood that all expenses would be covered by the Japanese, and they should expect to make about $3,000, depending on paid attendance at the games. On July 25, when the Giants lost, 7-5, to the Cincinnati Reds on a Saturday afternoon before 8,454 fans at the Polo Grounds, the team voted 18 to 7 to go to Japan.

Two players who voted yes were Sal Maglie and Hoyt Wilhelm. Several weeks later Maglie backed out, citing his ailing back, which needed to heal during the offseason. Ronnie Samford, an infielder and the only minor leaguer to make the trip, replaced Maglie. Hoyt Wilhelm faced a dilemma: His wife was pregnant. But his brother was serving in Korea. He chose to make the trip when he learned he could visit his brother during the tour.

Only two players’ wives opted to make the trip and at least one dropped out prior to departure. One obvious absentee was the Giants’ sensational center fielder who was the Rookie of the Year in 1951: Willie Mays. Serving in an Army transport unit in Virginia, he would not be discharged until after the tour ended, but in time for Opening Day in 1954.

Players who voted no provided a variety of reasons for their decisions. Alvin Dark and Whitey Lockman cited business commitments made before the invitation arrived; Rubén Gómez was committed to playing another season of winter ball in his native Puerto Rico; Bobby Thomson’s wife was pregnant; Larry Jansen preferred to stay home with his large family in Oregon; and Dave Koslo wanted to rest his aging arm. Tookie Gilbert also voted no but offered no reason for his decision.

Nonplayers in the traveling party included owner Stoneham and his son, Peter; manager Leo Durocher and his wife, Hollywood actress Laraine Day; Commissioner Frick and his wife; Mr. and Mrs. Lefty O’Doul; equipment manager Eddie Logan; publicist Billy Goodrich; team secretary Eddie Brannick and his wife; and coach Fred Fitzsimmons and his wife. Also making the trip was National League umpire Larry Goetz, who was appointed by National League President Warren Giles and Commissioner Frick.

The traveling party’s itinerary was straightforward. Most members left New York on October 8 and, after meeting the rest of the group in San Francisco, flew to Hawaii on October 9 and played two exhibition games. They left Honolulu on October 12 and arrived in Tokyo on October 14. After completing their 14-game schedule against Japanese teams, they left Tokyo on November 10 for Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam before returning to the United States.

Another team of major leaguers was touring Japan at the same time. Eddie Lopat’s All-Stars, including future Hall of Famers Yogi Berra, Enos Slaughter, Eddie Mathews, Nellie Fox, Robin Roberts, and Bob Lemon, and recent World Series hero Billy Martin, were sponsored by the Mainichinewspaper, one of Yomiuri Shimbun’s major competitors. Lopat’s team won 11 of 12 games and earned more money than the New York Giants.

THE TOUR IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

When Dwight D. Eisenhower assumed the US presidency on January 20, 1953, he inherited a Cold War abroad that was intertwined with the nation’s second Red Scare at home. The Soviet Union engulfed Eastern Europe with what Winston Churchill referred to as an iron curtain; and China, which witnessed a Communist revolution in 1949, became a major threat in Asia. On June 25, 1950, nearly 100,000 North Korean troops invaded US-backed South Korea, commencing the Korean War, which lasted until 1953.

The invasion had a major impact on Japan-US relations. In particular, the United States had to reevaluate how to address the rise of communism in Asia as well as quell the growing opposition to US military bases in Japan. On September 8, 1951, representatives of both countries met in San Francisco to sign the Treaty of Peace that officially ended World War II and the seven-year Allied occupation of Japan, which would take effect in the spring of 1952. Japan would be a sovereign nation again, but the United States would still maintain military bases there for security reasons that would benefit both countries. In short, “it was during the Korean War that US-Japan relations changed dramatically from occupation status to one of a security partnership in Asia,” opined an American journalist. And such an arrangement needed to be nurtured by soft-power diplomacy in the form of educational exchanges, visits by entertainers, and tours by major-league baseball clubs. In 1953 the New York Giants served as exemplars of soft power under the new partnership between the United States and Japan.

A CELEBRATORY ARRIVAL AND A SUCCESSFUL TOUR

The Giants easily won their two games in Hawaii. The first was a 7-2 win against a team of service allstars, and the second was a 10-1 victory over the Rural Red Sox, the Hawaii League champions in 1953. Also present in Honolulu was Cappy Harada, who talked of his dream of seeing a “real World Series” between the US and Japanese champions, while emphasizing that the quality of Japanese baseball was getting closer to the level of play of American teams. He noted that the Yomiuri Giants and the New York Giants had split two games during spring training. “We beat the Americans in California and they beat us in Arizona,” he said. Then, almost in the form of a warning to the traveling party that was about to depart for Japan, Harada reminded reporters that Yomiuri was a powerhouse, having led its league by 16 games.

When the Pan American Stratocruiser carrying the Giants landed at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport at 1:00 P.M. on October 14, it was swarmed by Japanese officials, reporters, photographers, and fans. Consequently, the traveling party could not move off the tarmac for more than an hour before boarding cars for a motorcade that wound its way through Tokyo streets lined with thousands of cheering fans waving flags, hoping to get a glimpse of the American ballplayers.

That evening in the lobby of the Imperial Hotel, Leo Durocher boldly stated that he expected his Giants to win every game on the tour. He also expected a home-run barrage by his club because the Japanese ballparks were so small. “We shouldn’t drop a game to any of these teams while we’re over here,” he boasted. Perhaps realizing that his comment was not the most diplomatic way to open the tour, Durocher quickly put a positive spin on his view of the Yomiuri Giants in particular. “They are the best-looking Japanese ball team I’ve seen,” he said. “They showed a great deal of improvement during their spring workouts in the States.” Yomiuri would win their third straight Japanese championship two days later.

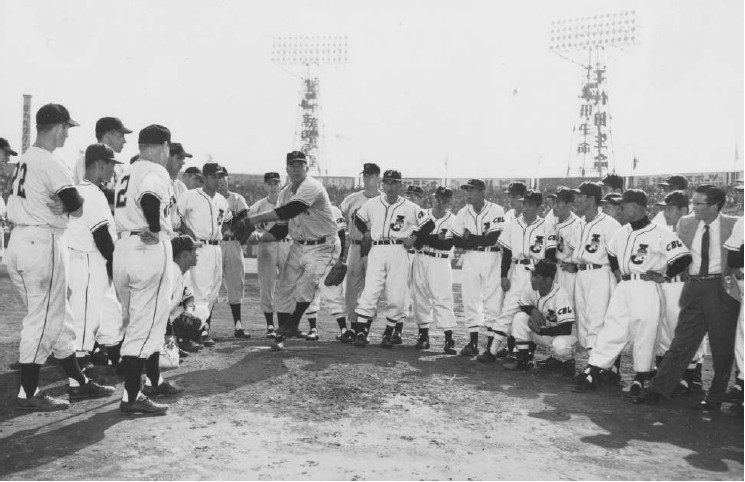

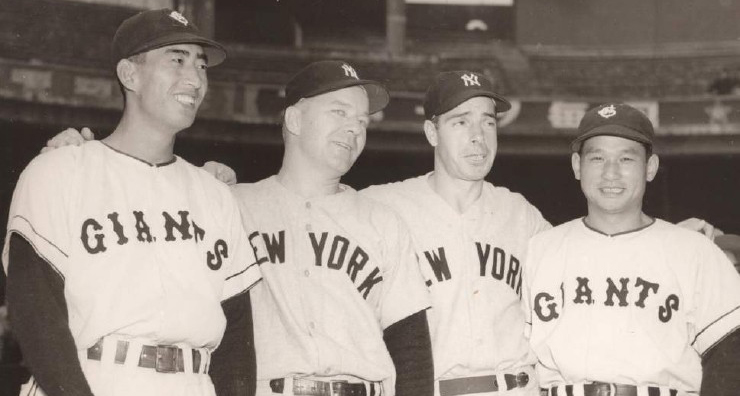

Over the next two days, the visiting Giants attended a large welcoming luncheon, participated in a motorcade parade through Tokyo, and held workouts at Korakuen Stadium. “Giants Drill, Leo’s Antics Delight Fans” read a headline in Pacific Stars and Stripes on October 16, the day before the series opened. Each day Durocher and several of his players conducted a one-hour clinic on the “fundamentals of American baseball.” A photo captured the Giants demonstrating a rundown play between third base and home.

Before the Giants’ arrival, the US Armed Forces newspaper Stars and Stripes published a two-page spread profiling the players on both teams. For the Japanese people, a Fan’s Guide was distributed widely. Gracing the cover was a color photograph of Leo Durocher with his arm around Yomiuri Giants manager Shigeru Mizuhara, a World War II veteran who had spent five years in a Soviet prison. Inside the guide were ads linked to baseball and numerous photos and profiles of players from both the New York Giants and Eddie Lopat’s All-Stars. Near the back of the guide, however, was an error: a photo of Mickey Mantle. Mantle had backed out of the trip with Eddie Lopat to undergo knee surgery in Missouri.

THE GAMES

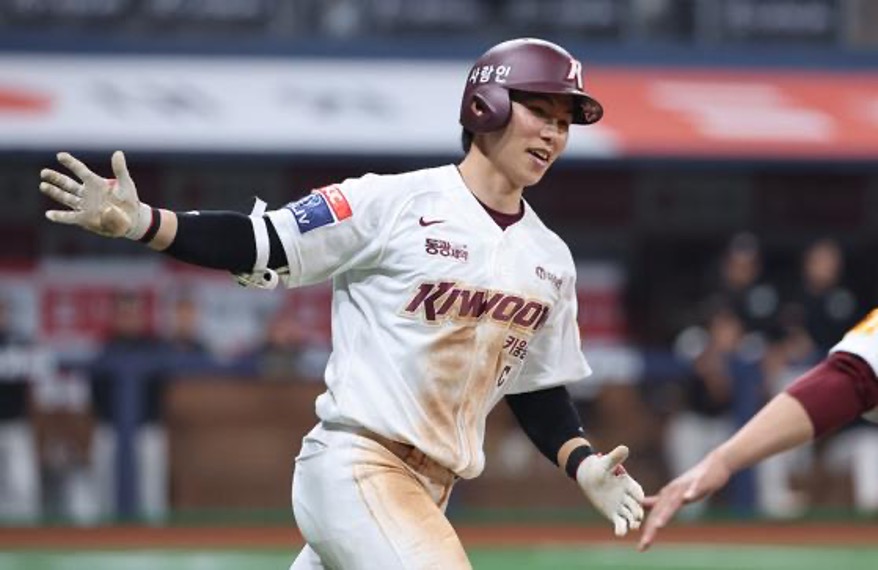

The team’s 14-game schedule was broken down into five games with the Yomiuri Giants, five games against the Central League All-Stars, two games with the All-Japan All-Stars, and single contests with the Chunichi Dragons and the Hanshin Tigers. The first three games were played in Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium, which held 45,000 fans.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website