The Hokkaido Nippon Ham Fighters have created this interesting video on their grounds keeper and how he keeps the field in immaculate condition.

Author: asianbaseballb45a112232

-

Japan’s First Filipino Player

YouTuber Gaijin Baseball presents this fascinating video on the little-known Adelano Rivera, who played for the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants in 1939.

-

Ichiro

A great article on Ichiro Suzuki on MLB.com that is worth sharing

https://www.mlb.com/news/featured/ichiro-suzuki-lasting-impact-on-baseball-japan

-

1934 All American tour of Japan footage

In 1934 the Yomiuri newspaper sponsored a team of American League all-stars to tour Japan. The team included future Hall of Famers Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Earl Averill, Charlie Gehringer, Lefty Gomez and Connie Mack as well as other stars and a backup catcher named Moe Berg. The All-Americans stayed for a month, played 18 games, and spawned professional baseball in Japan. You can read more about the tour in the book Banzai Babe Ruth.

This YouTube post contains colorized footage from the first two games of the tour (November 3 & 4, 1934)played at Meiji Jingo Stadium in Tokyo. Some of the colors are a bit off– some reds appear to be blue– but it’s still a fun window into the past.

-

Lend-Lease Athletes: John Britton & Jimmie Newberry

by Adam Berenbak

This post is a summary of a talk, titled “Lend-Lease Athletes: John Britton & Jimmie Newberry, Post-Integration Negro Leagues, and Japanese Pro Baseball at the end of the US Occupation” to be given at the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, July 26th, 11AM, during the weekend that Ichiro Suzuki will become the first Japanese born player to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Amid the celebration of Ichiro as the first Japanese baseball superstar to be enshrined in Cooperstown, I thought it important to recall two pioneers at another intersection of multiple baseball firsts – involving the Negro Leagues, Japanese pro ball, Jewish baseball and Major League Baseball. While their story isn’t new, Induction weekend seems like the right time to revisit these two amazing athletes.

Before Jimmie Newberry and John Britton made history as the first African American ballplayers to suit up in Nippon Professional Baseball (Jimmy Bonner, a veteran of Black independent teams, pitched several games in the earliest iteration of pro ball in Japan for Dai Tokyo in 1936), they each put together solid careers in the Negro American League, primarily with the Birmingham Black Barons. Both were looking for work after the 1951 Season when Bill Veeck provided an opportunity.

In March of 1951, Bill Veeck, then owner of several minor league clubs including Oklahoma City and Dayton, had scouted several Japanese players (all from the Mainichi Orions of Japan’s Pacific League), including Kaoru Betto and Hiroshi Oshita, but with his eye specifically on pitcher Atsushi Aramaki. Already plotting to sweep in to purchase the St. Louis Browns in July of that year, Veeck had not shed his propensity stretching the rules of the game and thumbing his nose at tradition and sought to bring a Japanese pro to the majors. On Dec 28, 1951, (at the NY opening of the Saints and Sinners Club), Veeck met with Teijiro Kurosaki, GM of the Orions, himself on a scouting trip to find American ballplayers, to discuss purchasing Aramaki’s contract for the Browns.

He could not seal the deal. By early 1952 Abe Saperstein (a minority stockholder in the Browns) was charged with developing contractual relationships with Japanese teams that would lead to the acquisition of Japanese stars to play in the US. Saperstein not only had relationships with Newberry, Britton, the Black Barons and the NAL, but was in regular contact with Japanese business interests as he planned several Japanese tours with the Harlem Globetrotters (who Veeck had helped promote through 1951). What unfolded was a relationship with the Hankyu Braves.

The Treaty of San Francisco ended the US Occupation of Japan on April 28, 1952, and on that day Veeck announced that he had reached an agreement with the Braves that would include loaning the newly acquired (to their minor league system) slugger John Britton and pitcher Jimmie Newberry from the Browns. Despite Veeck’s statement of diplomacy, the eventual goal was to open ties to the extent that NPB teams would negotiate the contracts of stars like Aramaki (who would go on to the Japanese Hall of Fame). Additionally, the timing was conspicuous, as contract negotiation would be much more feasible in a post-occupation world. Having brought 42-year-old Satchel Paige to the majors when he ran the Indians, Veeck was no stranger to controversy in pursuit of victory. As Veeck was also infamous for his promotional antics with the Browns, which would include the Eddie Gaedel incident, his motivation for fielding Japanese born players in the US remains murky. Whether it was a gimmick, a true attempt at competitive advantage, or a way to mine cheap labor, is unclear. It could be all three. Veeck’s reputation, as well as Saperstein’s problematic relationship with supporting and exploiting marginalized athletes (see Rebecca Alpert’s “Out of Left Field”) provide valuable context to what would be a first step in post-war international baseball contract negotiation.

Jimmie Newberry and John Britton had both been stars of the Birmingham Black Barons and veterans of the Negro League World Series, as well as former teammates of Willie Mays. Both would end up as Pacific League All Stars in 1952, and Britton would stay for a second season with the Braves, paving the path for Larry Raines and Jonas Gaines. He is probably the only person to face both Satchel Paige and Victor Starffin (he hit a home run off the latter). Neither Newberry nor Britton would make the Majors, for the Browns nor any other team.

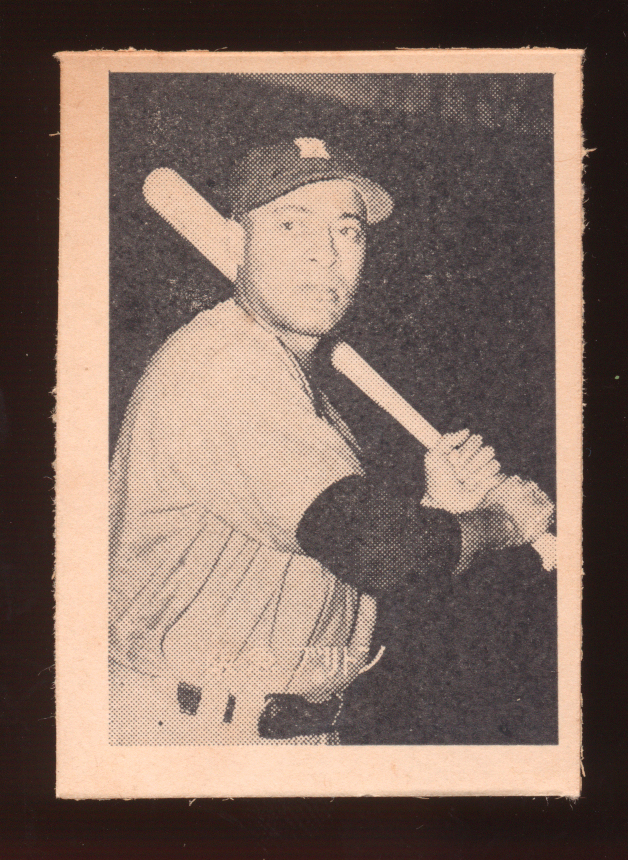

John Britton, 1952 Yamakatsu bromide Both of these pioneers have their own SABR bios, and their story appears in several well-known books on baseball in Japan (including “Wally Yonamine” by Rob Fitts), so there is not much in the way of new scholarship here. However, it’s interesting to note that several reports appearing in overseas newspapers refer to the two as “Lend-Lease” ball players, a journalistic embellishment referring to the famous policy in which the US lent weapons, goods and food to support the war effort at ostensibly no cost, but with provisions for eventual debt repayment. The act pre-dated Pearl Harbor by six months, an oversized event perhaps bookended by the official end to the occupation.

The term seems to be unintentionally inciteful. Beyond the obvious reference to Veeck’s machinations, and elements of diplomacy and international trade & support in a kind of battle (i.e. sports), “Lend-Lease” as a term can be seen as reflective of how professional baseball players, and especially marginalized ballplayers, including Japanese and Black ballplayers, were seen as property or commodities. This resonates especially with the history of slavery and racism imbedded in the African American baseball experience. The fact that both Newberry and Britton not only excelled but laid the groundwork for the success of future Black athletes in Japan is a testament to overcoming the “Lend-Lease” perspective. However, “lend lease” also reflects the reality of their situation as more and more Negro League teams began to disband, and baseball jobs were hard to come by. The fear of many Black sportswriters (including Joe Bostic) regarding how integration would affect the future of the Negro Leagues was no doubt a part of the reticence of Japanese clubs to deal with Major League Baseball. This seems even more instructive in light of the failure of Veeck or Saperstein to promote them to the Browns, or to lure Japanese talent to the US.

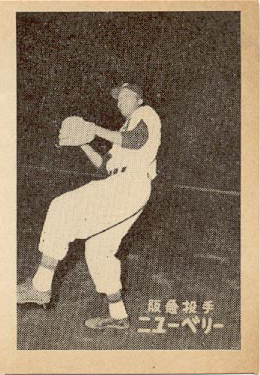

Jimmie Newberry, 1952 Yamakatsu bromide In part, one might attribute some of Newberry and Britton’s success to cultural differences. Time and time again there are stories of African American ballplayers, before and after integration, who found a more hospitable reception in the cities and states of South & Central America, escaping the racism these men endured as they traveled the US. While some racist imagery can be found of Newbery and Britton’s stay in Japan, and there has always been a noted resistance for the majority of Japanese pro baseball to welcome foreigners (especially Americans), both players found a similarly hospitable reception and enjoyed their time in the country. In addition, this occurs at the end of the US occupation, a time of complex feelings towards the US in Japan, although in the world of baseball an overwhelmingly receptive one to western culture.

Though ultimately unsuccessful, in the immediate sense, as an avenue to build a contractual bridge between Japan and the US as a way for Japanese players to head west, this episode was an important step in both forging a path for greater acceptance of Black and US born ballplayers as well as establishing the diplomatic framework for the relationship between NPB and MLB teams – one that would eventually lead to Masanori Murakami, Hideo Nomo, Ichiro and beyond.

-

Check out the new video The Story of Nomomania!

The Los Angeles Dodgers have just released a fantastic video on Youtube called The Story of Nomomania. With great game footage and exclusive interviews with Hideo Nomo, Peter O’Malley, Mike Piazza, and Don Nomura, I think fans will truly enjoy watching.

-

How to Follow Asian Professional Baseball

by Zac Petrillo, Jerry Chen, and Rob Fitts

So how can English speakers follow Asian baseball? There are now numerous ways to track professional baseball in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan even if you don’t read the native languages. Let’s look at each country in turn.

Japanese Baseball (NPB)

Just five years ago, it was difficult for English speakers outside of Japan to follow NPB, but now there are so many ways and sites to follow Japanese baseball that I can only list a small number here. Numerous sites post daily results, standings, and statistics on the web. Some sites that I find useful include the official website of Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB.jp), yakyucosmo.com, proeyekyuu.com, baseball reference.com, and flashscore.com. Japan-baseball.jp, the home page of Samurai Japan, contains schedules, rosters, scores, and information on all the national baseball teams. Those seeking more advance statistics may want to look atNPBstats.com and Delta Graphs which have incredible databases of traditional and sabermetric stats covering the entire history of Japanese professional baseball.The r/NPB group on Reddit is the most active social media site in English dedicated to NPB, with thirty-one thousand members in 2024. Members post game scores, standings, video highlights, and links to stories on other platforms. It is also a great place to ask questions about the game, learn how to buy tickets, find memorabilia, and read about other topics. One can also browse Japanese-language sport sites, such as Sportsnavi, and individual team sites and use a translation Ap, although I have not had much luck with this approach as the translations are often poor.

A great resource for following Japanese baseball is japanball.com, the home for the baseball tourism company JapanBall. Their site includes pages featuring each NPB team and stadium, articles on the history of the game and current players, exclusive interviews, current NPB news, game schedules and statistics, and information on their organized tours of Japan. You can also sign up for weekly updates on NPB via email.One of the easiest ways to follow NPB is by subscribing to select YouTube channels. Pacific League TV Official is a Japanese-language channel that contains over twenty-two thousand videos, including game highlights, player profiles, and much more. Pacific League Marketing also has an English-language channel called Pacific League TV, with nearly two thousand videos. The channel contains highlights, features on top Japanese and foreign players, archived games with English commentary, a podcast, and my favorite: the top-ten plays of the week.

There are two other can’t-miss YouTube channels for English-speaking fans. The Gaijin Baseball channel is one of my favorites. It contains about one hundred videos on the history of Japanese baseball. The stories are well researched and often contain compelling narratives with great graphics. This is the best place on the web for a beginner to learn about the history of the game in Japan. JapanBall has recently started a YouTube channel which contains updates of the current season as well as features on individual players and selected topics.

In July 2025, former NPB and KBO player David McKinnon along with journalist Jasper Spanjaart created Pacificswings.com. This site features video discussions of Asian baseball along with interviews of current and past players.

Full games, albeit with Japanese commentators, are also available. Pacific League games are easily viewed on Pacific League TV, a subscription service run by Pacific League Marketing that provides live games and archived games dating back to 2012. As the name suggests, the service only contains games from the Pacific League, along with interleague games held in Pacific League ballparks. Besides the games, the Pacificleague.com website contains thousands of videos, including game highlights, player profiles, news, and feature stories and league and player stats. The website and the games are in Japanese only, but there is an English-language page providing directions on how to join and navigate the site. As discussed above, Pacficleague.com also runs two YouTube channels, one in Japanese and one in English.

There is no single location to watch Central League games, but one can subscribe to various teams’ streaming channels or subscribe to a Japanese cable TV package. For example, Nozomi provides over eighty Japanese channels, allowing one to watch many Central League games both live and archived for two weeks after the initial broadcast. Programs can also be recorded. More information on watching Japanese baseball games can be found in this excellent article on japanball.com.Korean Baseball

For English-speaking baseball fans, following the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO) is easier than ever, thanks to a growing number of platforms offering games, highlights, and stats in English or with minimal language barriers.

The most comprehensive way to watch KBO games live in the U.S. is via SOOP, which streams every game live with Korean commentary. While it lacks English audio, it’s perfect for fans who want real-time access to all matchups.

For English-language coverage, the best option is the KBO Channel on Plex. Each day, one game is streamed live with Korean play-by-play, followed by a 24/7 replay stream of recent games, all featuring English AI commentary. This makes it easy for fans to catch up at any time and follow the season in their time zone.

If you prefer highlights, the official KBO YouTube channel is a reliable source. Although entirely in Korean, it features medium-form highlight packages for every game, with key hits, big strikeouts, full innings, and significant moments. The visual focus makes it easy to follow even without understanding the commentary.

For real-time stats and box scores, MyKBO Stats is the top destination for English speakers. Created by Dan Kurtz, the site provides live box scores, team and player stats, and historical data going back to 2013. It’s a must-bookmark for serious fans. You can also follow Kurtz on X (formerly Twitter) for regular updates and news.

For those looking for deeper analytics and historical data, STATIZ is a goldmine. Though the site is in Korean, it works well with browser-based translation tools and offers advanced stats and box scores all the way back to the league’s founding in 1982. It’s ideal for fans interested in diving into the numbers behind the game.

A few Korean news organizations provide KBO coverage in English. The most notable is the Yonhap News Agency, which regularly publishes game recaps, player profiles, and league developments. Their best-known KBO reporter is Jee-ho Yoo, a respected Seoul-based journalist and KBO expert whose work is a go-to resource for international readers.

Social media is another excellent way to stay connected. The X account “KBO in English” is run by an English-speaking fan based in Korea and offers regular updates and fan-friendly insights. It’s a great way to build familiarity with the league, players, and teams from a Western perspective. Also worth following is Daniel Kim (@DanielKimW), a bilingual baseball analyst who became widely known during ESPN’s KBO coverage in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While KBO content is still largely in Korean, English-speaking fans have options to follow the league. SOOP delivers every game live, Plex’s KBO Channel provides English commentary and 24/7 replays, MyKBO Stats covers real-time stats and historical data, and STATIZ offers deep analytics for those willing to use browser translation. Add in highlight reels on YouTube and fan-run social accounts, and there’s a whole ecosystem ready for English-speaking fans to dive into Korean baseball.

Taiwanese Baseball (CPBL)

Founded in 1989, the CPBL is more popular than ever, having recently benefited from the completion of Taipei Dome in 2023 and Taiwan’s Premier12 championship in 2024. The league currently consists of six teams who play most of their home games in six stadiums across the country:

- CTBC Brothers – Intercontinental Stadium, Taichung (YouTube)

- Fubon Guardians – Xinzhuang Stadium, New Taipei (YouTube)

- Rakuten Monkeys – Rakuten Taoyuan Stadium, Taoyuan (YouTube)

- TSG Hawks – Chengcing Lake Stadium, Kaohsiung (YouTube)

- Uni-President Lions – Tainan Municipal Stadium, Tainan (YouTube)

- Wei Chuan Dragons – Tianmu Stadium, Taipei (YouTube)

Taiwanese baseball has very limited English-language coverage. The best source currently is the CPBL official website, which publishes real-time box scores, season schedule, standings, team rosters, and stats in English. Besides the CPBL website, the only major resources for English speakers are:

- CPBL Stats – news and stats in English; the site’s X account (@gocpbl) regularly posts news and video clips

- r/cpbl on Reddit – predecessor to CPBL Stats and a good place for updates and questions

- The Taipei Sun – a newer initiative to cover Taiwanese baseball, including players abroad, in English

To watch CPBL games, fans can stream via Twitch (available for some teams only) or purchase a CPBL TV subscription from HamiVideo. As of July 2025, subscription plans for home games for each team are ~$2.70/month, or for all games ~$10.30/month. CPBL Stats has an English Guide to CPBL TV that is a bit dated but should still be helpful.

-

Tony Barnette & Aaron Fischman Zoom Event

On Thursday, July 10, 2025 SABR’s Asian Baseball Research Committee hosted its first Zoom event. Our guests were former Yakult Swallows closer and Texas Ranger Tony Barnette and author Aaron Fischman. Tony and Aaron spoke about their Casey- Award-nominated book, A Baseball Gaijin, as well as Tony’e experiences in Japanese baseball.

This fascinating event can now be view in its entirety on SABR’s YouTube channel.

-

Newly Identified Newspaper Article Pushes Earliest Date of Japanese Baseball Back to July 1869

by Robert K. Fitts

In 2022 Japanese baseball celebrated its official 150th birthday. Most officials and historians date the introduction of baseball to Japan to 1872 when American teacher Horace Wilson taught the game to his Japanese students. Recent research, however, has shown that the crew of the U.S.S. Colorado played against American residents of Yokohama in October 1871, and perhaps against Japanese residents of Osaka in January 1871[1] Now, a newspaper article shows that baseball was played as early as July 1869 in Kobe.

A few years ago, historian Aaron M. Cohen began sending me clippings about Japanese baseball from his files. Among the clippings was an article written by Harold S. Williams in 1976 discussing the origins of Japanese baseball. Williams was an Australian who lived in Kobe, Japan, from 1917 to his death in 1987, except for the war years. Williams wrote extensively about the early history of Kobe and Japanese culture.

In his article, “Shades of the Past: The Introduction of Baseball into Japan,” Williams argued “the names of those who actually first introduced the game into Japan is something which never will be known. Furthermore nobody knows, nobody can ever know, exactly where or precisely when the first game was played. Certainly it would have been a very modest and informal affair”[2] A sentence in the article caught my attention. He wrote: “in Kobe, on 4th August, 1869, about eighteen months after the port was opened, The Hiogo News reported: …one evening last week we saw as many as 7 or 8 men playing cricket and a still larger number playing baseball.”

Intrigued, I shared this with my colleague from Kawasaki, Japan, Yoichi Nagata. Yoichi went to the National Diet Library in Tokyo to track down the original source. The text of the article, appearing on page 434, is as follows.

“The exuberant spirit of youthful Kobe has been disporting itself for some days past a little out of the beaten track. This is a fact that, in spite of all kinds of adverse circumstances, the enthusiasm of a few cricketers has burst through the bonds that hitherto bound it, and bat, ball and stumps have been paraded through our streets. …The practice ground—no, it would not be right to call it by that name—the ball–splitting ground, or the ground upon which play has been carried on, has been the N.E. corner of the “sand patch” of a year ago—now well overgrown with weeds, grass, etc., etc. The best of this has been selected, the grass has been cut, and it makes a fair ground for practice. If anyone is skeptical on this point, he should join in an evening’s play, but novices should be fairly warned of the surrounding dangers, or the drains and stakes may cause a nasty tumble. The stakes are the corner posts of the different unsold lots, and those who have run against them say they are pretty firmly driven in. These are minor disadvantages, and the cricketeers say that a man never runs against them twice,—memory acts as a kindly warning, and one proof of their stability has hitherto been found quite sufficient.Truly, the “sand patch” has been used for purposes never dreamed of, and that it was apparently least fitted for. Two successful Race Meetings have been held on this non-elastic turf, and one evening last week we saw as many as 7 or 8 men playing cricket, and a still larger party playing baseball.We are pleased to hear it is the intention of the cricketeers to form a club, and wish them every success. Although there is sufficient talent here to form a good club, we fear the obstacles in the way of success are greater than are anticipated, unless the promoters are fortunate enough to secure a plot of ground at a very small expense, such, for instance, as an unused portion of a Race Course (should a Race Course be made here.) To buy or rent a piece of ground will entirely will be entirely beyond the means of such a club as can be formed here. A large piece of ground is required—say from 3,500 to 4,000 tsubos, and this at the lowest Japanese rental will amount to a very considerable figure yearly, to say nothing of the cost of preparing and keeping it in repair. The most feasible plan we have heard proposed is that permission should be obtained to use a certain portion of the N.E. corner of the Concession, level it, and cover it with mould, turf, &c. This scheme has few objections. The cost will be trifling, and in a few months, a decent practice grounds can be made. As the land is not likely to be required for some time, we think the Native Authorities would have very little objection to it being used for the purpose. We are aware the ground would be anything but perfect, and far from what a fine player would desire… .”

In March 2025 Yoichi and I returned to the Diet Library to search the Hiogo News for more early references to baseball. Unfortunately, we came up empty.

The “sand patch” mentioned in the Hiogo News article was not a particular location within Kobe but rather was a nickname for the entire area allocated for the foreign settlement. With a few exceptions, Japan was closed to foreigners from the beginning of the seventeenth century until American Admiral Matthew Perry entered Tokyo Bay with his Black Ships in 1853 and demanded access to the country for trade. The subsequent 1854 Convention of Kanagawa and 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce opened seven ports for trade and allowed for a foreign settlement, or Concession, at each port.

The Kobe Concession was opened on January 1, 1868. The land set aside for the foreign settlement was a barren sandy plain with poor drainage. Soon dubbed the “Sand Patch,” it became a swamp with knee deep quicksand during the rainy season and a dusty wasteland during the dry season. Early settlers began reclaiming the land and constructing trading houses and homes. By mid 1868, the area had been surveyed and laid out with staked plots ready for sale. Within the first year, the settlement’s small population (it contained about 200 Westerners in 1871) established two newspapers, social clubs, and on March 1, 1869, a horse racing club.

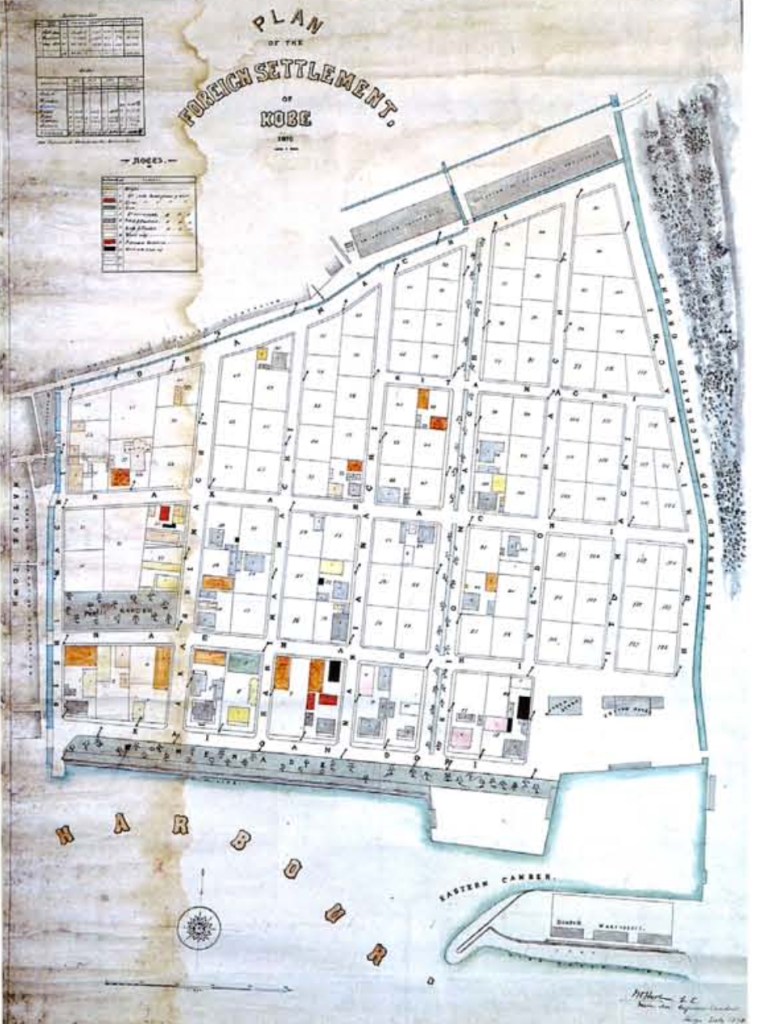

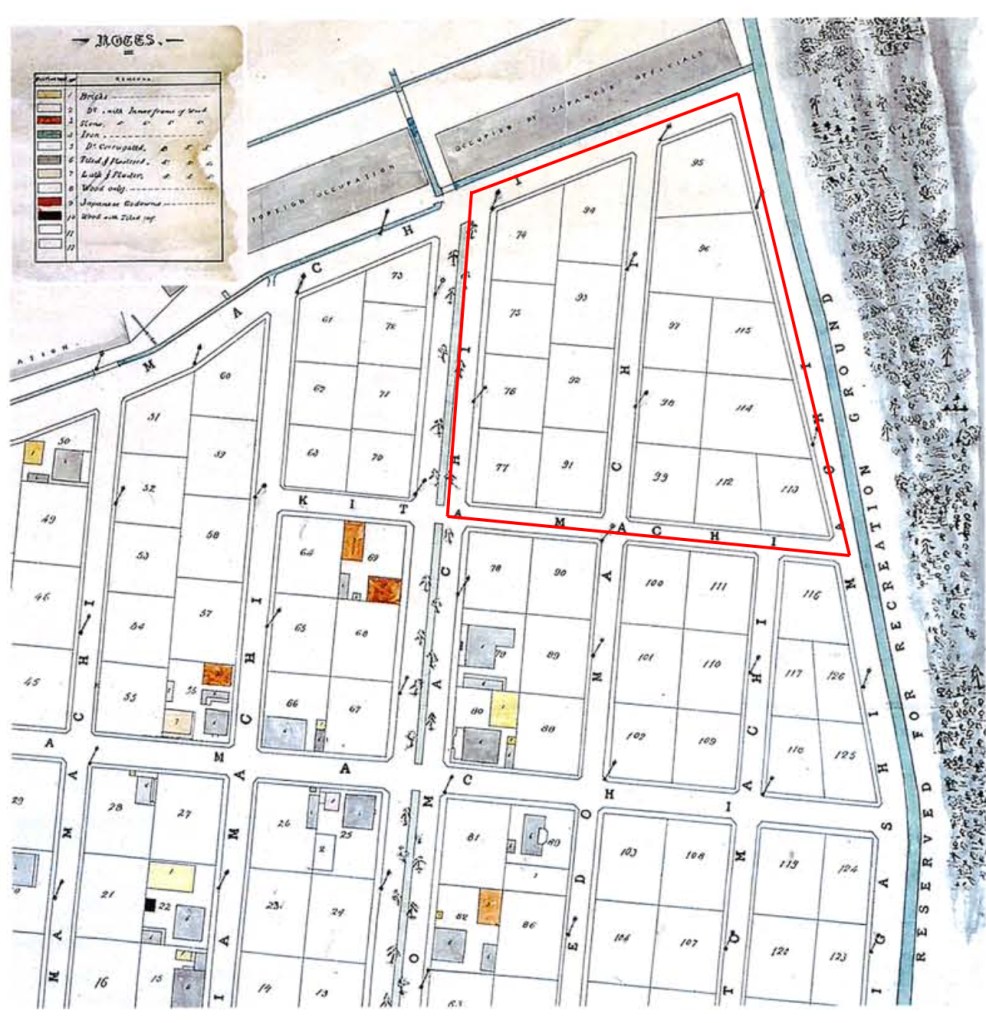

1868 map of Kobe showing the foreign concession on the right An 1870 plan of the Kobe Concession shows the location of the staked plots for sale and the approximate location of the ground used for cricket and baseball in July 1869. As the article clearly states that the ground was in the northeast corner of the concession and contained stakes marking the unsold lots, we can place the area just to the west of modern Kobe City Hall between Kyomachisuji Street on the west, Hanadokeisen Street on the north, Higashimachi-Suji Street on the east, and Kitamachi Street on the south.

1870 Plan of Kobe’s Foreign Settlement

Detail of the 1870 plan showing location of ball grounds

Location of ball grounds on modern map Sadly, Williams is correct that we may never know the identities of these early ballplayers. A complete list of early Kobe settlers that includes nationalities does not seem to exist. Therefore, we cannot identify the American residences who may have played in this July 1869 game.

In September 1870 the foreign residents of Kobe established the Kobe Regatta & Athletic Club and in 1872 reached an agreement with the Japanese authorities to create a recreation ground on the land just east of the concession where future cricket and baseball games were held.

With the digitization of newspapers and other sources from Meiji Japan, I expect that future researchers will find more evidence of early baseball in Japan. But Williams is probably correct that we will never know the exact date and location of first baseball game in Japan.

[1] Nobby Ito’s research on the 1871 game in Osaka is summarized in Michael Clair’s August 17, 2024, article on MLB.com “Search for Japan’s baseball origins unearths new possibility.”

[2] Williams’s article was originally published in the 1976 Journal of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan and was republished in Culture, Power & Politics in Treaty Port Japan, 1854-1899: Key Papers, Press and Contemporary Writings, edited by J.E. Hoare (Amsterdam University Press, 2028).

-

Firsts in Japanese Baseball

by Yoichi Nagata

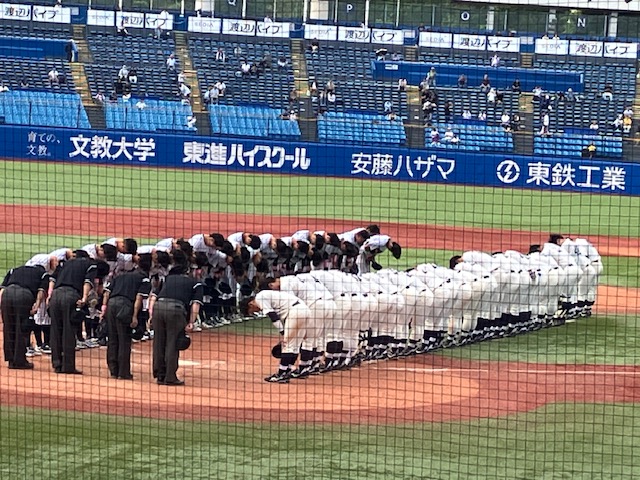

In the 2024 season, American baseball fans were curious to witness two Japanese players, Shohei Ohtani and Shota Imanaga, bowing to each other on the field during the warmup time before the regular season game between the Dodgers and the Cubs. Bows are seen everywhere on Japanese baseball grounds. Probably the most well-known ground bow is seen during the annual spring and summer Koshien high school tournaments. Players from each team line up on the both sides of home plate and bow facing each other before and after the game. It is a ritual in Japanese scholastic baseball.

When and where did the ritual of the pre-and post-game bow on the field begin? In 2022, the official 150th anniversary of Japanese baseball, the ad hoc baseball committee consisted of NPB, the Baseball Federation of Japan and the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum concluded that the Tohoku Six-Prefecture Middle School Baseball Tournament in Sendai, Miyagi, sponsored by the Second Higher School, initiated the ritual on November 3-5, 1911. It was incorporated into a regulation of Koshien baseball in 1915, when the tournament was first held.

The history book of Zenkoku Chuto Gakko Yakyu Taikaishi (History of National Middle-School Baseball Tournament) published in 1929 reveals the idea behind the ritual.

“Bushido (the spirit of Samurai) and sportsmanship have elements in common. However, Yakyu is baseball based on Bushido, apart from American professional baseball. And this is a baseball tournament to promote and spread baseball in Japan. Scholastic baseball must follow the ritual of the Japanese way, “The Bushido match starts with a bow and ends with a bow.”

However, I have found Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun of April 9, 1897 reporting the ritual in the game between Yamaguchi Higher School and Kumamoto Daigo Higher School in Fukuoka, Kyushu. “Players of the two teams came out to the field, and formed two lines and bowed to each other.”

Besides Yomiuri, two Fukuoka local papers of April 6, 1897, Fukuryo Shimbun and Fukuoka Nichinichireported alike.

The Yamaguchi school, hungry for a good opponent, sent a letter of challenge to the Kumamoto school for a baseball game. In front of the eyes of professors and students from both schools, the Kumamoto school pounded the Yamaguchi school, 21 to 2.

“The moment the game was over yells erupted from both cheering groups, “Banzai Daigo Higher School!” and “Banzai Yamaguchi Higher School!” Amidst of the shouts, the nine players of each team made its own line and bowed facing each other in the same manner of the pregame way (Fukuryo Shimbun and Fukuoka Nichinichi Shimbun of April 4, 1897).”

The ritual of the pre-and post-game bow, we now see in high school games at Koshien and college games at Jingu Stadium, was performed fourteen years before the Sendai tournament. However, considering the fact that baseball was introduced to the land of Bushido around 1870, it is unthinkable that for almost 30 years prior to the Fukuoka game, bows had not been performed on baseball grounds.

Post-game bow in the game between Rikkyo University and Meiji University in the Tokyo Big 6 League at Jingu Stadium, May 11, 2025 I am also interested in another example of “first” in Japanese baseball history. The first admission-charged game was considered for a long time Game 1 between the St. Louis College alumni team from Honolulu and Keio University at Tsunamachi ground, Tokyo, on October 31, 1907 to pay off the travelling expenses of the Hawaii team. However, I have found four newspapers, Tokyo Mainichi Shimbun, Jiji Shimpo, Kokumin Shimbun, and Japan Weekly Mail, reporting that the game between Yokohama Cricket and Athletic Club (YC&AC: a sports club of foreign residents) and Waseda University at Yokohama Park on October 12, 1907, nineteen days before the St. Louis and Keio game, was a paid game to keep the spectators section in order. After my continuous research since then, I am not able to conclude that this was the first admission-charged game yet, because a newspaper suggests some games were so before the YC&AC and Waseda game. The paper doesn’t specify which games were.

Recently, we learned that baseball was played in Japan as early as 1869, however, it was thought for many years baseball arrived in Japan in the early 1870s. I wonder how far back firsts of the ritual of pre-and post game bow and admission charged game stretch.

-

MID-DECADE MILESTONES IN U.S.–JAPAN BASEBALL RELATIONS (1875–2025)

by Bill Staples, Jr.

A 150-Year Journey Through the Game That Bridges Nations

Ichiro Suzuki’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame on July 27, 2025 is a milestone worth celebrating—and an opportunity to reflect on the progress of U.S.–Japan baseball relations. From Ichiro’s enshrinement to the sandlot games played by Japanese school children during the 1870s, the history of baseball between the U.S. and Japan is a rich narrative of cultural exchange, perseverance, diplomacy, and innovation.

With that in mind, I thought it would be fun to use Ichiro’s 2025 achievement as a springboard to explore key mid-decade milestones (years ending in five) in the U.S.–Japan baseball journey. Let’s look at how the sport evolved from a foreign curiosity into a shared national passion—and ultimately, a bridge between two nations.

Let’s begin in the present and work our way backward.

NOTE: The full version of this article with all illustrations and links is available on Bill Staples, Jr’s blog, International Pastime.

https://billstaples.blogspot.com/2025/04/mid-decade-milestones-in-usjapan.html

2025

Ichiro Suzuki was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2025, receiving 393 out of 394 votes (99.75%) in his first year on the ballot. This made him the first Japanese-born position player elected to Cooperstown, though he fell one vote shy of unanimous selection—a distinction held by Mariano Rivera in 2019. In anticipation of his enshrinement, the Hall of Fame created a new exhibit titled Yakyu | Baseball: The Transpacific Exchange of the Game. The exhibit will open in July 2025 and remain on display for at least five years. Learn more at: https://baseballhall.org/yakyu. 2015

Ichiro, now with the Miami Marlins, begins symbolically “passing the torch” to Shohei Ohtani, who is in the second year of his professional career with the Nippon Ham Fighters in Japan. The 2015 season marks Ichiro’s first appearance as a pitcher, setting the stage for a rare and unexpected future Hall of Fame connection between Ichiro and Ohtani—two Japanese-born players who both pitched and hit a grand slam during their MLB careers. Ichiro hit just one grand slam, while Ohtani has hit three (as of this post), and intriguingly, all of them against the Tampa Bay Rays.2005

Tadahito Iguchi becomes the first Japanese-born player to compete in and win a World Series, contributing to the Chicago White Sox’s historic run. (Note: Hideki Irabu received a World Series ring as a member of the 1998 and 1998 New York Yankees but did not play in any postseason games). Check out Iguchi’s SABR Bio.1995

Hideo Nomo joins the Los Angeles Dodgers, earning Rookie of the Year, an all-star game start, and igniting “Nomomania.” His success breaks open the modern pipeline between NPB and MLB and reshapes the perception of Japanese players on the global stage. Check out Nomo’s SABR Bio.1985

Pete Rose breaks Ty Cobb’s all-time hit record using a Mizuno bat. After visiting Japan in 1978, Rose teamed up with sports agent Cappy Harada to sign a sponsorship deal with Mizuno in 1980. Rose’s partnership with Mizuno marked a significant moment in sports history, symbolizing Japan’s growing influence in global sports and helping to establish Japanese manufacturers as credible names in American dugouts and MLB clubhouses.1975

The Chunichi Dragons, led by manager Wally Yonamine, and the Yomiuri Giants, led by manager Shigeo Nagashima, conduct spring training in Florida. Meanwhile, American-born manager Joe Lutz and Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn contribute to Japanese baseball by joining the Hiroshima Carp. Lutz becomes the second U.S.-born manager in NPB history after WWII, following Hawaii-native Yonamine. However, Lutz’s time with the Carp is short-lived, as he steps down just weeks into the new season. Spahn continues his role with the Carp and states that he prefers working in Japan compared to the U.S.

Joe Lutz, Hiroshima Carp 1975 1965

Masanori Murakami finishes his rookie season with the San Francisco Giants after debuting in 1964, becoming the first Japanese-born player in MLB. His success inspires generations of Japanese players to dream of American stardom.

Masanori Murakami 1955

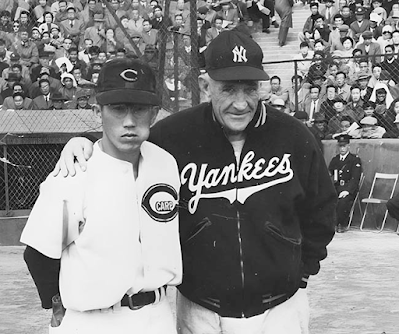

After a season in the minor leagues and facing lingering post–World War II anti-Japanese sentiment, California native Satoshi “Fibber” Hirayama chose to continue his professional baseball career in Japan, signing with the Hiroshima Carp. That same season, the New York Yankees toured Japan, and afterward, former Japanese pitching star and Hawai‘i native Bozo Wakabayashi was hired as a scout for the team. However, Yankees manager Casey Stengel resisted the idea of signing Japanese players, citing concerns about adding new talent to an already talent-heavy roster.

Fibber Hirayama with Casey Stengel, 1955 1945

In the aftermath of World War II, baseball became a source of healing and pride for Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated behind barbed wire. At the Gila River camp in Arizona, the Butte High Eagles stunned the defending state champions, the Tucson High Badgers, with an 11–10 extra-innings victory. Coach Kenichi Zenimura called it “the greatest game ever played at Gila.” After graduating, Eagles second baseman Kenso Zenimura relocated to Chicago, where he attended the East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park and watched Kansas City Monarchs standout Jackie Robinson during his lone season in the Negro Leagues.

Kenichi Zenimura at Gila River in 1945 1935

The founding of the Tokyo Giants paved the way for the launch of the Japanese Professional Baseball League in 1936. During the team’s groundbreaking U.S. tour, four players — pitchers Victor Starffin and Eiji Sawamura, infielder Takeo Tabe, and outfielder Jimmy Horio — attracted interest from American professional clubs and may have received contract offers. However, the 1924 Immigration Act rendered Japanese-born players ineligible to sign with U.S. teams. Only one player—Hawaii-born Horio—was eligible under U.S. law. He signed with the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League for the 1935 season but returned to Japan the following year to join the Hankyu Braves in the new professional league.

Jimmy Horio with Sacramento in 1935 1925

Sponsored by the Osaka Mainichi newspaper, a semipro team called Daimai was formed and sent on tour in the United States, where they faced American universities and semi-pro clubs, including the Japanese American Fresno Athletic Club (FAC). In early September, the FAC played a doubleheader at White Sox Park in Los Angeles—the first game against Daimai, and the second against the L.A. White Sox, the premier Negro Leagues team in Southern California. Behind the strong pitching of Kenso Nushida, FAC edged out the White Sox 5–4, setting the stage for rematches in 1926 and parallel tours of Japan in 1927. White Sox manager Lon Goodwin rebranded his team as the Philadelphia Royal Giants for the Japan tour, ushering in a new era of international baseball exchange.

Catcher O’Neal Pullen and pitcher Jay Johnson of the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1927. Negro Leagues Baseball Museum 1915

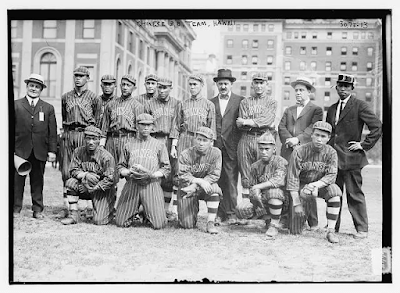

The Hawaiian Travelers, a barnstorming team made up of Chinese and Japanese Americans from the Hawaiian Territories, toured the U.S. mainland in the early 20th century. Two Japanese players, Jimmy Moriyama and Andy Yamashiro, joined the team under assumed Chinese identities, playing as “Chin” and “Yim.” The Travelers impressed fans and opponents alike with victories over top Negro League clubs such as the Lincoln Giants and Brooklyn Royal Giants—both teams now designated as major league caliber by SABR. After a return tour, Yamashiro, still using the name Andy Yim, signed with the Gettysburg Ponies of the Class D Blue Ridge League in 1917, quietly becoming the first Japanese American to join an integrated professional team—though history recorded him only under his adopted identity. Meanwhile, an Osaka newspaper, Asahi Shinbun, sponsors a national tournament for high school teams that eventually becomes one of the most popular sporting events in Japan (known today as the Koshien Tournament).

The Hawaiian Travelers in 1914 1905

The 1905 Waseda University baseball tour was the first time a Japanese college team traveled to the United States to compete, playing 26 games along the West Coast and finishing with a record of 7 wins and 19 losses. The team was led by Abe Isō, a Waseda professor, Unitarian minister, and politician who saw baseball as a powerful tool for international exchange and cultural diplomacy. Although Waseda struggled on the field, the tour was a landmark moment in U.S.–Japan relations, helping to lay the groundwork for future athletic and cultural connections between the two nations. Meanwhile, John McGraw of the New York Giants gave a tryout to a Japanese outfielder known as “Sugimoto.” However, shortly after Sugimoto’s arrival at spring training, discussions in the press about enforcing the color line surface. In response, Sugimoto chose to leave the tryout of his own accord.

1905 Waseda University Baseball 1895

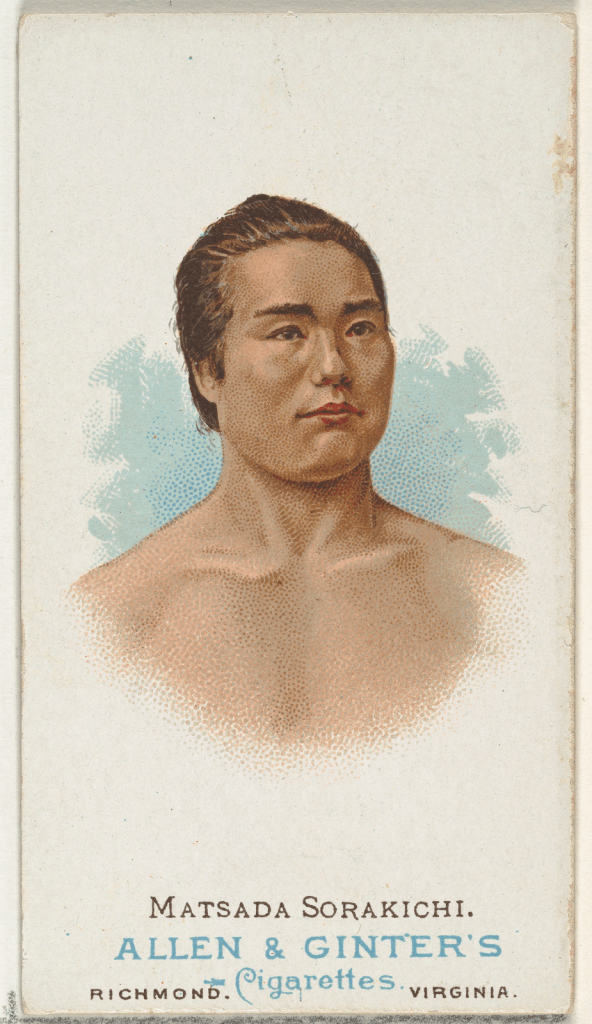

Dunham White Stevens, the American Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Washington, was described as “a baseball crank” and persuaded Japanese Minister Shinichiro Kurino to join him at several games. This gesture reflected one of the earliest examples of diplomatic engagement through sport. Meanwhile, Japanese American ballplayers were competing in amateur leagues in Chicago, and by 1897, a promising outfielder—identified in the press only as the cousin of wrestler Sorikichi Matsuda—was reportedly scouted by Patsy Tebeau, manager of the major league Cleveland Spiders.

1887 Allen & Ginter trading card of Sorakichi Matsuda 1885

Sankichi Akamoto, a young Japanese acrobat and baseball enthusiast, played the game in America, blending cultural performance with sport. His presence foreshadowed the dual role many Japanese athletes would later assume—as both competitors and cultural ambassadors. Around the same time, at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, Japanese student Aisuke Kabayama competed on the school’s tennis and baseball clubs, eventually earning a spot on the varsity baseball team the following season. His participation is believed to be the earliest recorded instance of a Japanese-born player in U.S. college baseball.

The Akimoto Japanese Troupe, circa. 1885. Robert Meyers Collection 1875

The seeds of Japanese baseball began to take root in the early 1870s, as people of Japanese ancestry played the game on both sides of the Pacific. In 1873, Albert G. Bates, an American teacher in Tokyo, organized what’s considered the first formal school-level baseball game in Japan. According to Japanese sports historian Ikuo Abe, the game occurred on the grounds of the Zojiji Temple in Tokyo (image below). Tragically, in early 1875, Bates died at just 20 years old from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning while visiting a public bathhouse.

“View of Zōjōji Temple at Shiba,” by Yorozuya Kichibei (1790-1848), Minneapolis Institute of Art -

Solving the Mystery of Togo Hamamoto

by Rob Fitts

Originally published on RobFitts.com February 15, 2021

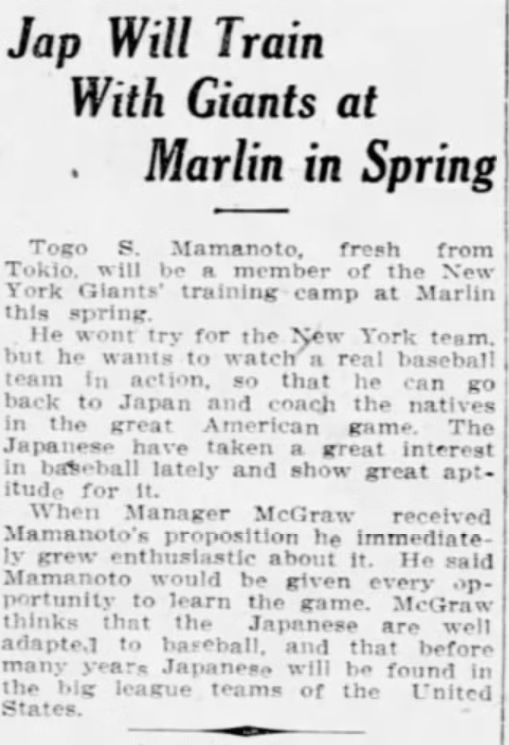

The history of early Japanese American baseball is still being discovered. There is so much we do not know. Mainstream, English-language newspapers rarely covered Japanese American daily life or sport. When these newspapers did mention Japanese immigrant baseball, the articles were often garbled—full of misspellings, factual errors, and sometimes overt bigotry. On top of this, early twentieth century sportswriters enjoyed telling an entertaining story more than report fact. Piecing together history from these articles is challenging as most of the reports cannot be taken at face value but instead need to be confirmed by independent sources. As an example, let’s examine the story of Togo Hamamoto.

In mid-January 1911, an intriguing article ran on the sports pages across the United States. On January 17th, New York Giants manager John McGraw announced that Togo S. Hamamoto of Tokyo would be joining the team at Marlin Springs, Texas, to observe American “scientific baseball.”

A press release noted that Hamamoto, “who has the backing of a number of influential citizens of Tokyo, . . . will devote his time to mastering the game.”[1] “His backers plan to add professional baseball in their own country.”[2] “McGraw plans to do all in his power to spread the gospel of the game in foreign lands,” the release continued. He “is prophesying that some day [sic] a real world’s championship will be played with the United States and Japan as rivals.”[3] Newspapers across the country, from large-market dailies to bi-weekly rags in rural villages, reprinted the announcement.

About a month later, Hamamoto was in the news again. This time, reporters had transformed him from an observer into a player receiving a tryout. “Togo is a star player among the Japs, and will work out daily,” reported the Chronicle-Telegram of Elyria, Ohio. “He may play on the second team.”[4] But of more interest to the writers were reports of Hamamoto bringing his valet and personal cook to training camp.

He “may do more than merely learn baseball. He threatens to change the entire social conditions of ball players,” joked an anonymous writer. “When the valet is seen trailing Togo’s baseball shoes after a workout with the Giants or perhaps pressing his suit and folding it neatly away in the locker to await the next practice, it is likely to strike the ball players’ fancy and before the Giants come north it is more than probable that Togo S. will lose the distinction of being the only ball player who has his own private valet.”[5] Another writer worried, “McGraw fears a valet oiling Togo’s shoes and fanning him between innings, may cause the Giants to insurge [sic] and ask for the same treatment.”[6]

On March 9, the sports editor of the New York Times asked, “Where is Togo Hamamoto, the Japanese athlete, who was going to train with the New York Giants at Marlin Springs? Togo burned up the cables getting permission from Manager McGraw to get inside information on training a baseball team, and McGraw gave him permission to join the camp. But he hasn’t appeared, and nothing has been heard from him.”[7] The Giants began practicing in Marlin’s Emerson Park on February 20 and stayed until March, practicing in Emerson Park. Reports from the Giants’ spring training camp fail to mention Hamamoto and newspaper articles do not provide a reason for his absence.

When I wrote the first draft of Issei Baseball in 2018, I wondered if the story was a hoax dreamed up by a bored sportswriter yearning for the start of the baseball season. My searches of immigration records found no man named Hamamoto arriving from Japan in 1911, plus his name does not appear in Japanese baseball histories. On top of that, his name is suspiciously similar to Irving Wallace’s fictional character Togo Hashimura, the Japanese “school boy” whose book of fictitious letters describing life in America had become a best seller in 1909. I concluded that the articles written about Hamamoto attending spring training were a hoax written for amusement.

That changed in early 2019 when I received a copy of Tetsusaburo “Tom” Uyeda’s previously classified FBI file. Uyeda, who had played on Guy Green’s 1906 Japanese Base Ball Team and the 1908 Denver Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team, was unjustly convicted in 1942 by the U.S. Alien Enemy Hearing Board as a Japanese spy. During his appeal, Uyeda explained; “In the Spring of 1912, I received a letter from one Mr. Hamamoto who asked me to come over to St. Louis, Missouri, to assist in organizing a baseball team.”[8]

Refocusing my research on St. Louis, I found a Togo S. Hamamoto listed in the city directory as valet working for Hugh Kochler, a wealthy brewer. Born Shizunobu Hamamoto in Nagasaki on December 25, 1884, he arrived in Seattle on the SS Shimano Maru on April 22, 1903. He made his way to St. Louis in 1906 and began working as a valet while reporting on Major League baseball for the Nagasaki-based newspaperSasebo. He attended four or five games per week and became friendly with a number of the players, including Cristy Mathewson, Lou Gehrig, and Babe Ruth [9].

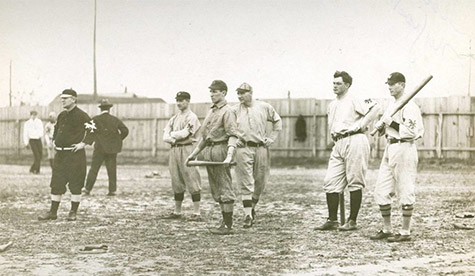

But did Hamamoto attend the Giants’ spring training in 1911? There was no evidence that he had until June 2020 when Robert Klevens, owner of Prestige Collectibles and an authority of Japanese baseball memorabilia, found this postcard.

The picture shows Hamamoto wearing a Giants uniform made between 1909 and 1910 (the team used a different logo on their sleeve in 1908 and switched to pinstripes in 1911). The solid stocking pattern was used by the Giants only in 1909, but we do not know if the Giants issued these to Hamamoto or if he wore his own stockings.

(Illustration from Baseball Uniforms of the 20th Century by Marc Okkonen

As new uniforms were expensive and teams did not have large budgets, it was common for players to practice in uniforms from previous seasons. This picture from spring training in 1912, for example, shows Giants players in various uniform styles.

I have not been able to locate enough pictures of Emerson Park to confirm if the photograph of Hamamoto was taken there, but the wooden fence in the photograph is similar to the fence surround the ballpark. Efforts to identify the Mr. S noted on the back has been fruitless.

So even though the postcard does not prove that Hamamoto attended the Giants spring training in 1911, it is likely that the newspaper stories were partly accurate and that he eventually arrived. Hamamoto’s time with the Giants, however, did not lead to a professional baseball league in Japan. Unsuccessful attempts to create a pro circuit did not begin until 1920s and it was not until the creation of Japanese Baseball League in 1936 that Japan would have a stable professional league.

Hamamoto would eventually turn his back on baseball. A few years later, he was in the stands watching his home-town Browns battle Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators when a St. Louis batter popped out in a key situation. “Some of the people behind me, and one of them was a lady, used such language—oh, it was so bad that I decided baseball did not always contain the three cardinal principals which I think a sport should have—Dignity, Honesty, and Humor. Since then I have not gone to ball games.”[10]

Around 1916, while still working as a valet for Kochler, Hamamoto took up golf. He played at every opportunity and soon mastered the sport. In 1929, he won St. Louis’s Forrest Park Golf Club’s championship and went on to play in several national amateur championships. Upon his father’s death in 1933, he returned to Nagasaki to inherit the estate. At the end of World War II, he became an interpreter for the police in Haiki, Japan.[11] The year of his death is unknown.

[1]Salt Lake Telegram, January 17, 1911, 7.[2] Akron Beacon Journal, January 18, 1911, 8.

[3]Salt Lake Telegram, January 17, 1911, 7.

[4]Chronicle-Telegram, February 23, 1911, 3.

[5]Winnipeg Tribune, February 24, 1911, 7.

[6]Elyria Chronicle-Telegram, February 23, 1911, 3.

[7]New York Times, March 9, 1911, 12.

[8] Tetsusaburo Uyeda to Edward J. Ennis, January 3, 1944. World War II Alien Enemy Detention and Internment Case Files, Tetsusaburo “Thomas” Uyeda, Case 146-13-2-42-36.

[9]St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1929, 19.

[10]St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1929, 19.

[11]St. Louis Star and Times, December 4, 1945, 22.