by Rob Fitts

The first Japanese professional baseball game took place not in Tokyo, not in Osaka, or even in Japan, but in a tiny town in Northeastern Kansas.

In 1906 much of United States was enthralled by Japan and all things Japanese. Japan had just emerged as the improbable victor in the Russo-Japanese War and the year before the Waseda University baseball club had toured the West Coast. Guy W. Green, the owner of the Nebraska Indians Baseball Club, decided to capitalize on the fad by creating an all-Japanese baseball team to barnstorm across the Midwest. It would be the first Japanese professional team on either side of the Pacific.

The early twentieth century was the heyday of barnstorming baseball. Independent teams crisscrossed the country playing in one-horse towns and large cities. There were all female teams, squads of only fat men, clubs of men sporting beards, and teams consisting of “exotic” ethnicities. These independent squads were often called “semi-professional” to differentiate them from teams in Organized Baseball (clubs formally associated with Major League Baseball), but they were professional enterprises. The teams signed players to contracts, paid salaries during the season, provided transportation and housing on the road, charged admission to games, and were intent on turning a profit.

Although Green would claim that he had “scour[ed] the [Japanese] empire for the best players obtainable,” he did nothing of the sort. In early 1906 Green instructed Dan Tobey, captain of the Nebraska Indians, to form a team from Japanese immigrants living in California. Players congregated our March 15 in Havelock, Nebraska for two weeks of practice. It soon became evident that not all of his recruits were strong enough to play on a professional independent squad, so Green and Tobey decided to bolster his roster with Native Americans —hoping that most spectators would not be able to tell the difference.

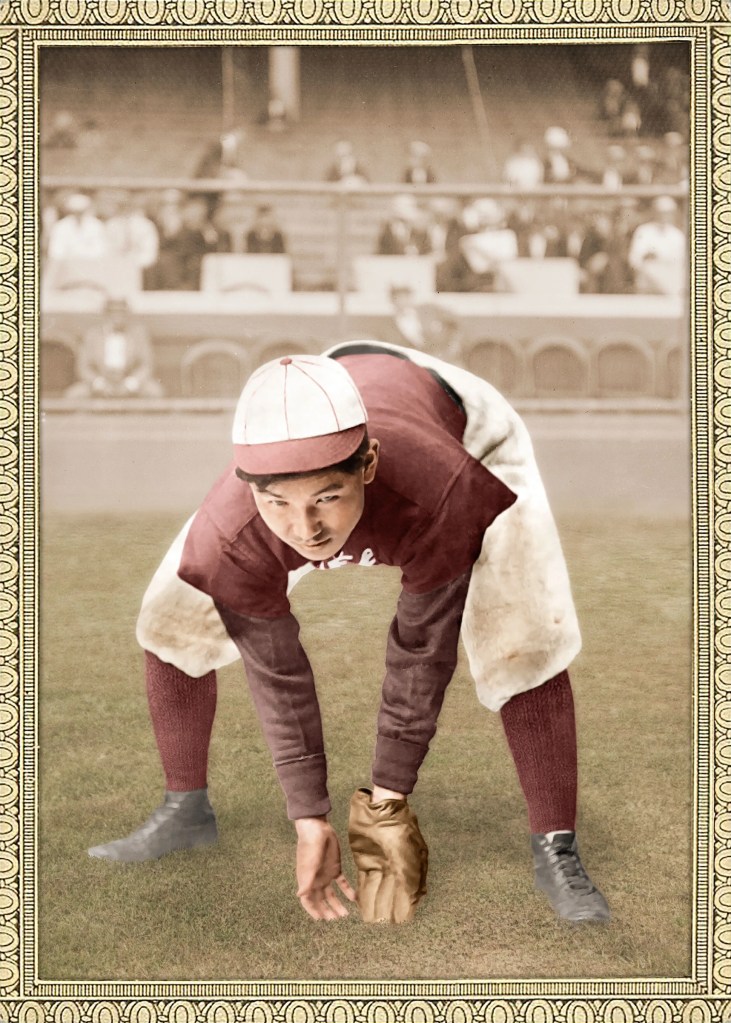

The starting lineup featured five Japanese: Toyo Fujita, a writer for the Rafu Shimpo newspaper, at first base; Tetsusaburo Uyeda from Yamaguchi Prefecture at second; 21-year-old Ken Kitsuse from Kagoshima at short; and 21-year-old Umekichi “Kitty” Kawashima from Kanagawa and a man identified only as Naito in the outfield. Manager Dan Tobey and Nebraska Indian veteran Sandy Kissell shared the pitching duties and played outfield on their off days. Seguin, another member of the Nebraska Indians, was the catcher. Roy Dean Whitcomb, an 18-year-old Caucasian from Lincoln, usually played third base under the name Noisy, while a man known only as Doctor filled in as necessary.

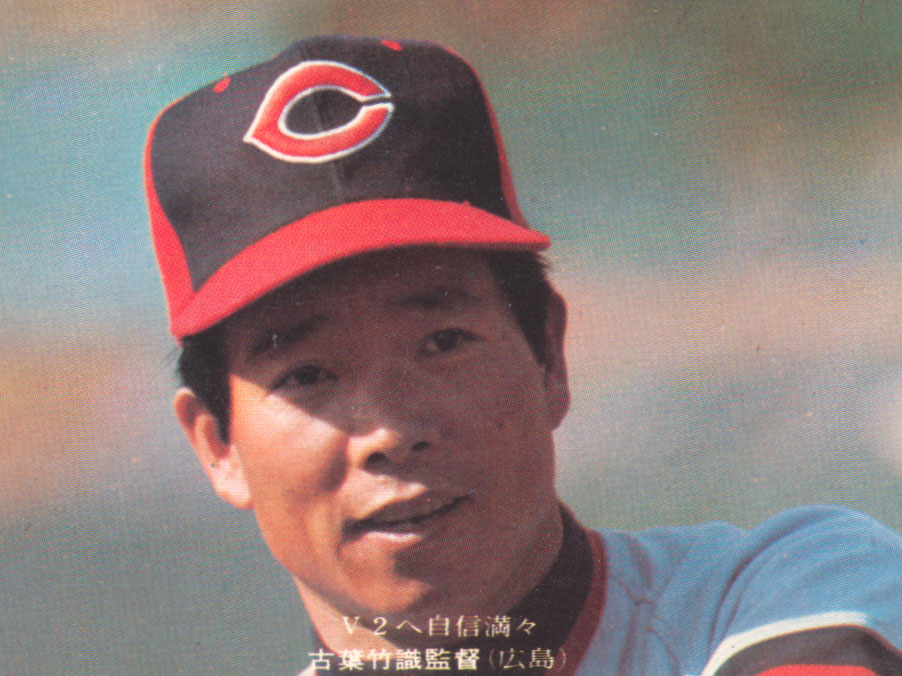

Ken Kitsuse Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame

On evening of April 13, Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team left Havelock and headed south to begin a twenty-five-week tour that would cover over twenty-five hundred miles through Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri. Their first stop was Frankfort, a small town of about 1,400 people in northeastern Kansas, where they would play the town’s high school squad.

Prior to the game, Guy Green sent out promotional material and flooded local newspapers with advertising and press releases. At the time, there were so few Japanese living in the Midwest that many rural farmers had never seen a Japanese person. So, Green’s advertisements emphasized the players’ foreignness and the uniqueness of the team. A typical announcement read, “Green’s [team] are the most novel baseball organization the world has ever known. Every player is a genuine Japanese. Not one of them can speak a word of English. They do all their coaching in Japanese and is certainly the most Japanesy Japanese you have ever listened to.”

Playing on the public’s fascination with the Russo-Japanese War, Green also concocted fictional backgrounds for his players. An April 13, 1906 article in the Frankfort Review noted, “One of the most interesting members of Green’s Japanese baseball team is Kitsuse, who left school in Japan to serve during the last great war with Japan. He was wounded in the left leg at Mukden so severely that he was compelled to go home and even yet he limps slightly. He is one of the best me on the team, however, and always a great favorite with the crowds.” Kitsuse, however, immigrated to California on June 8, 1903, almost two years before the 1905 Battle of Mukden.

On Sunday, April 15 the two teams met on a leveled field just outside of town. There were no grandstands or bleachers—spectators sat and stood on a raised berm that surrounded the diamond. The high schoolers took the field in brand-new red and grey uniforms that had just arrived a couple of days before. The Japanese squad wore white pants reaching just below the knees, wide leather belts, maroon stockings, maroon undershirts, and a winged-collared maroon jersey with “Greens Japs” stitched in white block letters across the chest. The caps were white with maroon bills.

As the high school contained just 41 students, the match should have been an easy victory for Green’s independent team. Perhaps seeing the game as an opportunity to allow his weaker players to gain experience, Tobey started a mostly Japanese lineup. But Tobey had underestimated the skinny, 15-year-old redhead on the mound. The teenage ace, Fairfield “Jack” Walker would go on to pitch for the University of Kansas in 1911-12 and professionally in the Class D Nebraska State League and the Eastern Kansas League. Although a quiet kid, the Horton Headlight noted “when playing Walker wears a perpetual grin that makes a lot of batters mad because they think he is laughing at them.”

Besides Walker, the school’s lineup consisted of George Moss behind the plate; a boy identified only as Russell at first; Harold Haskins at second; Willis Cook at third; Leo Holthoefer at short; and Robert Barrett, John McNamara and Walker (unknown first name) in the outfield.

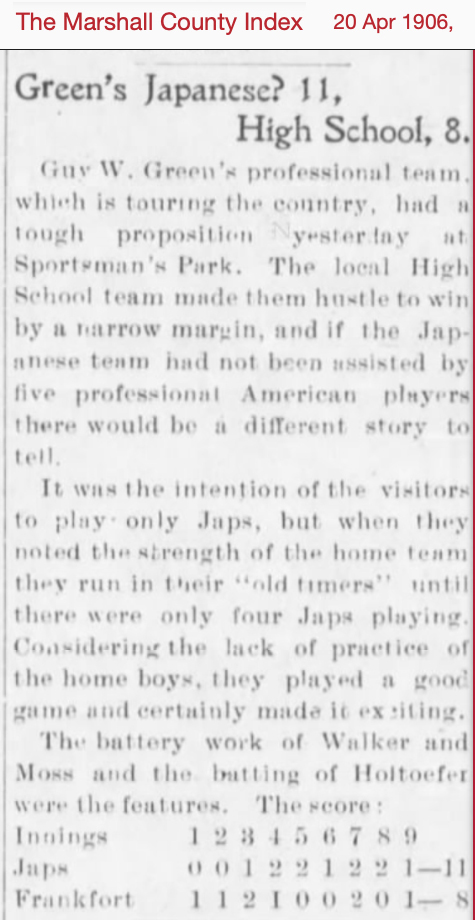

The schoolboys jumped out to an early 4-1 lead after three innings, forcing Tobey to bring in what the Marshall County Index called “five professional American players.” The visitors battled back, scoring in every inning after the second, to eventually win 11-8. The Frankfort Review reported, “A large number of people witnessed the game and they prounce [sic] it one of the best games ever played here.”

The near loss to schoolboys confirmed Tobey’s view that many of his Japanese players were not talented enough for an independent team. Green’s Japanese squad would stay on the road until October 10, playing about 170 games and winning 122 of the 142 games for which results are known, but there is no record of the team using an all Japanese starting lineup again.

Despite the lengthy tour and the uniqueness of the club, The Sporting News, as well as big market newspapers in New York, Washington and Los Angles, did not cover or even mention Green’s Japanese team. As a result, the first professional Japanese players had little impact on the national or international baseball scene and were soon forgotten. But the tour marked the true beginnings of Japanese-American baseball. After the season, the players headed back to the West Coast to form independent Japanese ball clubs. The Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team of Denver would barnstorm in Colorado and Kansas in 1908, while the Nanka of Los Angeles would play at the amateur level before changing its name to the Japanese Base Ball Association and becoming an independent barnstorming team in 1911. These teams’ success helped spawn numerous Nikkei clubs as baseball became an integral part of the Japanese-American community and culture.

You can read more about the Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team and the early pioneers of Japanese American baseball in my new book Issei baseball: The First Japanese American Ballplayers (University of Nebraska Press, 2020).

I would like to thank Alice Jones of the Frankfort City Library and Dwight “Skip” McMillen for their invaluable help searching the archives in Frankfort, Kansas.

Identified Frankfort Players

Frank Robert Barrett (born April 16, 1888 Frankfort KS – died December 28, 1968 Los Angeles)

James Willis Cook (born April 30, 1887 Frankfort KS – died December 13, 1960 San Anselmo, CA

Harold Haskins (born ca. 1892- 12/6/1918, died in the 1918 influenza epidemic)

Leo Holthoefer (born January 1, 1886 Atchinson, KS – died December 12, 1927 Denver, CO)

John McNamara (born 1890, Nebraska)

George Edward Moss (born October 6, 1887 Frankfort KS – died June 13, 1961 Frankfort KS)

Fairfield “Jack” Walker (born February 20, 1891 Frankfort KS – died 1951, Wichita, KS)