by Adam Berenbak

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Adam Berenbak tells us about the 1922 MLB tour led by Herb Hunter.

THE PLOT

The Polo Grounds. New York’s National League champs were on the verge of beating the mighty Yankees for the second year in a row. The 1922 World Series was once again a series in one park, as each game for the past two years had found a home at Coogan’s Bluff. As the triumph neared, Herbert Hunter, a former Giant attending the game, received a cablegram inviting him and the stars of the Series on a tour of Japan. Eager to capitalize on this moment, he recruited several Yanks and Giants, including the dashing George Kelly, to make the trip across the Pacific. Little did they know that they had just been swept up in an international plot to corrupt baseball, a plot not too distant from the Black Sox conspiracy that had nearly ruined faith in the great game.

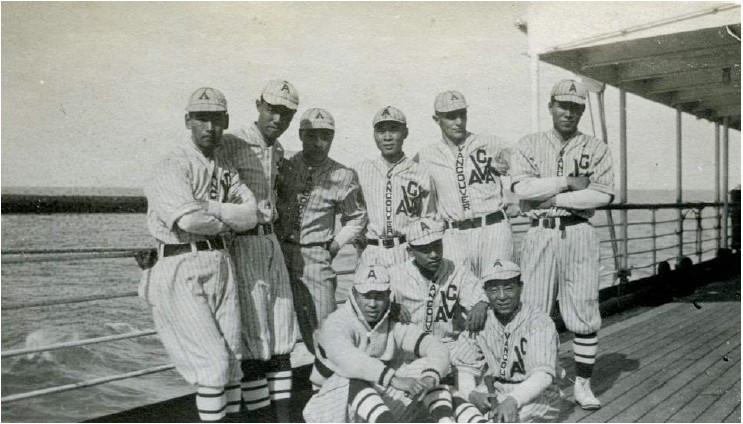

Luckily for the history of the sport, this was not the truth of the 1922 tour of Japan, nor a plot in any sense other than fictional. The United Pictures Company had assembled a team of actors, both American and Japanese, as well as a loose script about an international conspiracy plot, to travel with the group of major-league all-stars, assembled by Hunter, during their trip overseas.Known officially as the All-American Baseball Team but often called the Herb Hunter All-Stars, they sailed across the Pacific after the 1922 season to face college and club teams that represented the height of Japanese talent. In addition to the professional actors, the American and Japanese ballplayers portrayed themselves in the film, participating in the unique experience of acting on two stages at once—in front of the crowds that gathered in Japanese ballparks as well as future crowds in theaters. It might be said that somewhere between fact and fiction lies the truth, and while the tour did not produce the kind of melodrama filmgoers would be eager to view, the games generated their own drama and myths, straddling that line between fact and fiction in the legacy of international baseball.

VANCOUVER

The Canadian Pacific Railway train number 1 arrived in British Columbia on October 17, 1922, carrying with it the team of major leaguers set to sail for Japan and begin a tour of baseball diplomacy. On the 19th the Vancouver weather held and the touring pros, led by Herb Hunter, opened their trip with a 16-1 walloping of Ernie Paepke’s local squad, providing a thrill to a crowd that had little access to major-league ball as well as a proper warm-up prior to the long boat ride to Japan. During the game, George Kelly, Irish Meusel, Joe Bush, and Fred Hofmann all saw playing time. Because all four had participated in the recent World Series, this technically broke the rules against Series stars barnstorming together. However, due to the pickup nature of the game, neither the press nor the players, and especially not the fans, seemed to care. The team boarded the Empress of Canada for Honolulu immediately after the game.

Once aboard and on their way, the team received a telegram from Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, hired as commissioner two years prior to clean up the game wrecked by what has become known as the Black Sox Scandal. Reports had reached Landis that the barnstorming rules he guarded with such ferocity had been broken. Just the year before, he had chastised, suspended, and fined Babe Ruth for similar barnstorming infractions. He was furious, especially after only reluctantly giving Hunter permission for the tour. The tourists communicated with home via Bob Brown, sponsor of the Vancouver game, to whom they messaged a wireless reply to Judge Landis’s barnstorming complaint. Brown in turn sent an explanation over the wire assuring Landis that there was no intentional rule-breaking and that the entire experience fostered nothing but goodwill and economic possibilities in the Northwest. What went unmentioned in the press was that the game was not on the printed schedule, and it was probably the unscheduled barnstorming that added to Landis’s ire. Landis made no reply but was reported sleepless over the incident. His objections to barnstorming, along with his reported racial prejudice, combined with the events of the 1922 tour to shape the relationship between US and Japanese baseball for the next decade.

Tour organizer Herbert Harrison Hunter had been a professional ballplayer since 1914, and signed with John McGraw’s Giants in 1915. Though he had been touted as a sure-bet prospect, Hunter was never able to fulfill those promises in New York or anywhere else in the big leagues. He had first made his way to Japan as part of the 1920 Gene Doyle tour that featured primarily Pacific Coast League players. An eccentric among eccentrics, and more of an entertainer on baseball’s stage, Hunter was always a dandy (to McGraw’s consternation and confusion), and enjoyed sticking out, wearing “a fresh chrysanthemum every day” and touring the nightlife of Tokyo as a celebrity. During the 1920 tour, Hunter began coaching the Waseda University nine. He seemed to enjoy the way the students looked up to him; he treated them to elaborate dinners and allowed them to worship him.

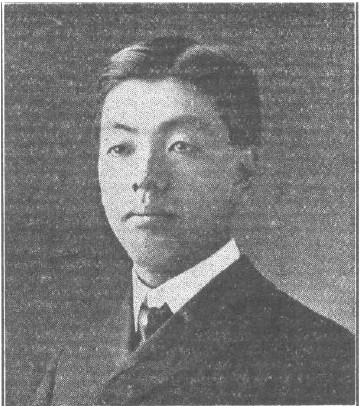

He found work back in the States in 1921, playing the majority of the year in the South Atlantic League before an end-of-season call-up to the St. Louis Cardinals. In the fall Branch Rickey released him in support of his endeavors in Japan. Though Hunter, bom in Boston on Christmas Day 1895, had played in only 39 games over four seasons with the Giants, Red Sox, Cardinals, and Cubs, his major-league experience, however brief, was highly valued in Japan. In the winter of 1921 and into early 1922, Hunter returned to Japan to coach both Waseda and Keio Universities and developed a friendship with the “father of Japanese baseball,” Isoo Abe.

With Abe’s help, a sponsorship by Mariya Sporting Goods, and the backing of the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper company, Hunter sought to arrange for a group of major leaguers, including Babe Ruth, to tour Japan after the end of the 1922 season.

Having witnessed the unrealized potential of the 1920 Doyle tour, as well as the value in the promise of Ruth, he knew the revenue was there. And it wouldn’t hurt to align himself with Ruth, the most popular player in the world, to achieve his financial and celebrity ambitions. After spending the whole winter in Japan, he sailed back in February of 1922 with a mission to build a roster, armed with a guarantee of $50,000, though it would be only to cover expenses. Hunter envisioned this as the first of what would be annual tours, with him at the center, his mission to promote himself as much as to establish regular international competition with a real “world series.”

Although Hunter had also worked with Keio as well as other teams that would eventually form the Big Six University system, it was his relationship with the Waseda team that played the biggest role in getting the first real major-league tour of Japan under way. Waseda was eager to become the dominant team in Japan as well as the foremost ambassador of the Japanese game. Between the beginning of 1920 and the All-Stars’ visit in the fall of 1922, the team had faced US competition seven times on both sides of the Pacific. Instrumental in their drive were Abe, who had founded the Waseda team and had led the first-ever transcontinental tour when his team traveled the US West Coast in 1905, and Chujun Tobita, a man on a mission. Tobita had played with the Waseda nine back in 1910 when the University of Chicago had beaten them soundly, and the loss inspired the second baseman. Now the manager of Waseda, he drove the team with his famous “death training,” developed to hone the skills and spirit of the young players. Success, in part, meant beating Chicago, and “[i]f the players do not try so hard as to vomit blood in practice, then they cannot hope to win games.”

With Waseda’s support, the backing of the Mainichi Shimbun, a tentative agreement from both American League President Ban Johnson and Landis that goodwill tours would benefit the game (as long as its participants conducted themselves as diplomats and nobody got injured), and even the support of President Warren Harding, who noted the tour’s “real diplomatic value,” Hunter assembled an all-star squad for the 1922 tour.

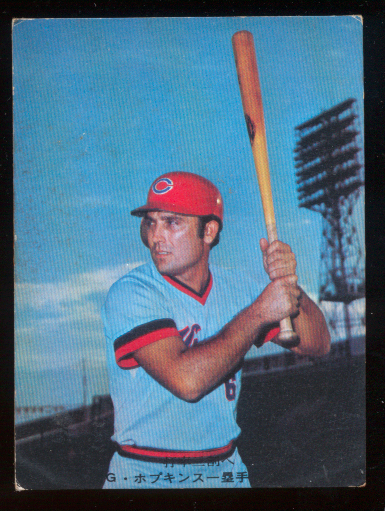

But first a roster would need to be constructed. Rogers Hornsby, Harry Heilmann, and Frank Frisch topped Hunter’s list, but all of his backers in Japan were especially pining for home-run hitters Babe Ruth and George “High Pockets” Kelly. Near the height of his fame, Ruth was a draw everywhere he went, and Japanese fans reportedly clamored for a chance to see him in person—something that didn’t happen for another 12 years. Ruth proved to be unattainable, and most of the others declined for various reasons—even an invitation to Art Nehf that was initially accepted fell through when John McGraw requested that he stay stateside.

In the end, Hunter secured the 1921 National League home run king George Kelly and put together a team featuring members of the 1922 World Series competitors. Included with Kelly were fellow Giants Casey Stengel and Irish Meusel, along with Waite Hoyt, Fred Hofmann, and Joe Bush from the Yankees. Also on the team were future Hall of Famer Herb Pennock, Amos Strunk, Brooklyn outfielder Bert Griffith, Luke Sewell, Riggs Stevenson, and Bibb Falk. Rounding out the group was John “Doc” Lavan, Hunter’s ex-teammate on the Cardinals. The agreement with Landis included a clause that the players would receive no 1923 contract until they reported to spring training in good health after returning from the tour. New York Sun sportswriter Frank O’Neill joined as an organizer as well as reporter, along with George Moriarty, who was along as much to be the eyes and ears of Landis as umpire. It may have been Moriarty who had reported the barnstorming infraction, but nonetheless his role seemed to be keeping an eye on the proclivities of some of those players prone to take a drink outside the confines of Prohibition. Some of the organizers’ and players’ wives accompanied the team, a request made in light of the 1920 tour’s unruly behavior.

After arriving in Yokohama on the last day of October, the Americans checked into the Tokyo Imperial Hotel. The hotel was one of the few structures to survive the great earthquake that struck Japan in September of the following year. That disaster, known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, devastated Tokyo and led to fires and tsunamis that killed more than 100,000 people.

Japan’s fortunes had fluctuated since the end of the Meiji period, a decade prior to Hunter’s tour. The silk market, and the stock market along with it, had crashed in 1920, and the country’s place on the world stage was precarious. Tension between the United States and Japan was high as arguments were about to begin in front of the US Supreme Court regarding barring immigrants of Asian descent from becoming naturalized American citizens.28 The importance of the diplomatic aspect of baseball tours grew as these tensions grew, and the 1922 tour proved how successful the tours could be. This diplomatic endeavor was showcased on the baseball diamond at the Shibaura Grounds in Tokyo’s Minato ward.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website