by Adam Berenbak

This post is a summary of a talk, titled “Lend-Lease Athletes: John Britton & Jimmie Newberry, Post-Integration Negro Leagues, and Japanese Pro Baseball at the end of the US Occupation” to be given at the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, July 26th, 11AM, during the weekend that Ichiro Suzuki will become the first Japanese born player to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Amid the celebration of Ichiro as the first Japanese baseball superstar to be enshrined in Cooperstown, I thought it important to recall two pioneers at another intersection of multiple baseball firsts – involving the Negro Leagues, Japanese pro ball, Jewish baseball and Major League Baseball. While their story isn’t new, Induction weekend seems like the right time to revisit these two amazing athletes.

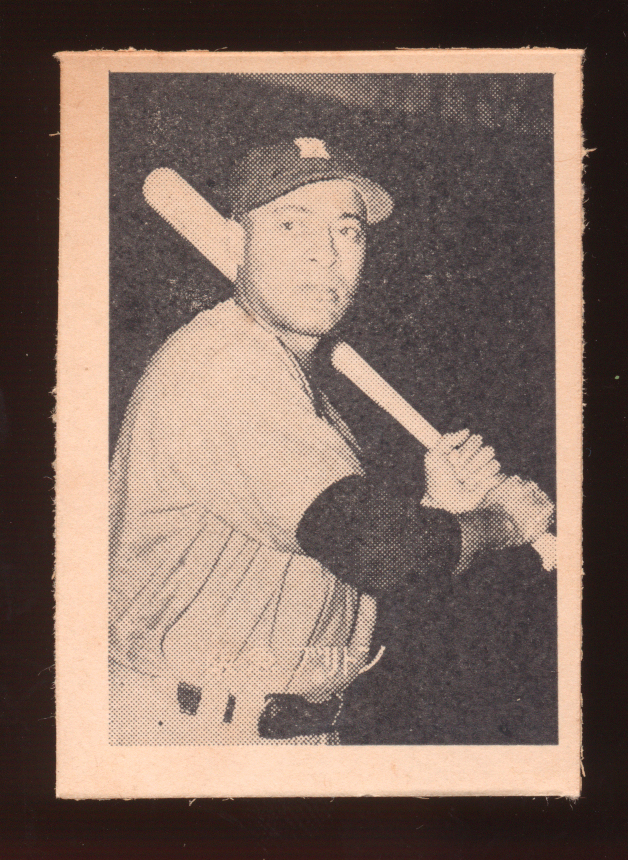

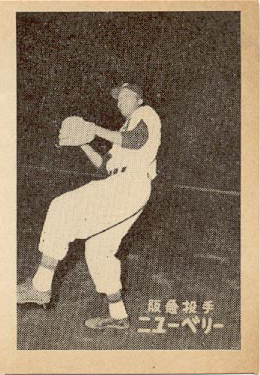

Before Jimmie Newberry and John Britton made history as the first African American ballplayers to suit up in Nippon Professional Baseball (Jimmy Bonner, a veteran of Black independent teams, pitched several games in the earliest iteration of pro ball in Japan for Dai Tokyo in 1936), they each put together solid careers in the Negro American League, primarily with the Birmingham Black Barons. Both were looking for work after the 1951 Season when Bill Veeck provided an opportunity.

In March of 1951, Bill Veeck, then owner of several minor league clubs including Oklahoma City and Dayton, had scouted several Japanese players (all from the Mainichi Orions of Japan’s Pacific League), including Kaoru Betto and Hiroshi Oshita, but with his eye specifically on pitcher Atsushi Aramaki. Already plotting to sweep in to purchase the St. Louis Browns in July of that year, Veeck had not shed his propensity stretching the rules of the game and thumbing his nose at tradition and sought to bring a Japanese pro to the majors. On Dec 28, 1951, (at the NY opening of the Saints and Sinners Club), Veeck met with Teijiro Kurosaki, GM of the Orions, himself on a scouting trip to find American ballplayers, to discuss purchasing Aramaki’s contract for the Browns.

He could not seal the deal. By early 1952 Abe Saperstein (a minority stockholder in the Browns) was charged with developing contractual relationships with Japanese teams that would lead to the acquisition of Japanese stars to play in the US. Saperstein not only had relationships with Newberry, Britton, the Black Barons and the NAL, but was in regular contact with Japanese business interests as he planned several Japanese tours with the Harlem Globetrotters (who Veeck had helped promote through 1951). What unfolded was a relationship with the Hankyu Braves.

The Treaty of San Francisco ended the US Occupation of Japan on April 28, 1952, and on that day Veeck announced that he had reached an agreement with the Braves that would include loaning the newly acquired (to their minor league system) slugger John Britton and pitcher Jimmie Newberry from the Browns. Despite Veeck’s statement of diplomacy, the eventual goal was to open ties to the extent that NPB teams would negotiate the contracts of stars like Aramaki (who would go on to the Japanese Hall of Fame). Additionally, the timing was conspicuous, as contract negotiation would be much more feasible in a post-occupation world. Having brought 42-year-old Satchel Paige to the majors when he ran the Indians, Veeck was no stranger to controversy in pursuit of victory. As Veeck was also infamous for his promotional antics with the Browns, which would include the Eddie Gaedel incident, his motivation for fielding Japanese born players in the US remains murky. Whether it was a gimmick, a true attempt at competitive advantage, or a way to mine cheap labor, is unclear. It could be all three. Veeck’s reputation, as well as Saperstein’s problematic relationship with supporting and exploiting marginalized athletes (see Rebecca Alpert’s “Out of Left Field”) provide valuable context to what would be a first step in post-war international baseball contract negotiation.

Jimmie Newberry and John Britton had both been stars of the Birmingham Black Barons and veterans of the Negro League World Series, as well as former teammates of Willie Mays. Both would end up as Pacific League All Stars in 1952, and Britton would stay for a second season with the Braves, paving the path for Larry Raines and Jonas Gaines. He is probably the only person to face both Satchel Paige and Victor Starffin (he hit a home run off the latter). Neither Newberry nor Britton would make the Majors, for the Browns nor any other team.

Both of these pioneers have their own SABR bios, and their story appears in several well-known books on baseball in Japan (including “Wally Yonamine” by Rob Fitts), so there is not much in the way of new scholarship here. However, it’s interesting to note that several reports appearing in overseas newspapers refer to the two as “Lend-Lease” ball players, a journalistic embellishment referring to the famous policy in which the US lent weapons, goods and food to support the war effort at ostensibly no cost, but with provisions for eventual debt repayment. The act pre-dated Pearl Harbor by six months, an oversized event perhaps bookended by the official end to the occupation.

The term seems to be unintentionally inciteful. Beyond the obvious reference to Veeck’s machinations, and elements of diplomacy and international trade & support in a kind of battle (i.e. sports), “Lend-Lease” as a term can be seen as reflective of how professional baseball players, and especially marginalized ballplayers, including Japanese and Black ballplayers, were seen as property or commodities. This resonates especially with the history of slavery and racism imbedded in the African American baseball experience. The fact that both Newberry and Britton not only excelled but laid the groundwork for the success of future Black athletes in Japan is a testament to overcoming the “Lend-Lease” perspective. However, “lend lease” also reflects the reality of their situation as more and more Negro League teams began to disband, and baseball jobs were hard to come by. The fear of many Black sportswriters (including Joe Bostic) regarding how integration would affect the future of the Negro Leagues was no doubt a part of the reticence of Japanese clubs to deal with Major League Baseball. This seems even more instructive in light of the failure of Veeck or Saperstein to promote them to the Browns, or to lure Japanese talent to the US.

In part, one might attribute some of Newberry and Britton’s success to cultural differences. Time and time again there are stories of African American ballplayers, before and after integration, who found a more hospitable reception in the cities and states of South & Central America, escaping the racism these men endured as they traveled the US. While some racist imagery can be found of Newbery and Britton’s stay in Japan, and there has always been a noted resistance for the majority of Japanese pro baseball to welcome foreigners (especially Americans), both players found a similarly hospitable reception and enjoyed their time in the country. In addition, this occurs at the end of the US occupation, a time of complex feelings towards the US in Japan, although in the world of baseball an overwhelmingly receptive one to western culture.

Though ultimately unsuccessful, in the immediate sense, as an avenue to build a contractual bridge between Japan and the US as a way for Japanese players to head west, this episode was an important step in both forging a path for greater acceptance of Black and US born ballplayers as well as establishing the diplomatic framework for the relationship between NPB and MLB teams – one that would eventually lead to Masanori Murakami, Hideo Nomo, Ichiro and beyond.

Leave a comment