by Taein Chun

MLB fans are familiar with the MLBPA. Strikes, negotiations, and collective action are deeply etched into the history of American sports. However, in Korean professional baseball (KBO), player rights were long treated as a taboo. Players were stars, yet at the same time they were almost like property of the club. If they spoke up, consequences awaited them. But the cries of a few players eventually began to change history.

Dong-won Choi: The First Voice for Player Rights

In the 1984 Korean Series, Lotte Giants ace Dong-won Choi led the team to victory in four out of five games. He was the hero of Busan and a symbol of Korean baseball. Yet at the peak of his career, he began another fight, this time about rights. At that time, Korean players were treated like the property of the club. Salaries were unilaterally dictated. If they raised objections, release or trade awaited them. Injuries were to be borne solely by the players, and there were no mechanisms to guarantee life after retirement. Dong-won Choi pointed out that “players’ lives are treated too lightly” and pushed to establish a players’ association.

His demands were simple: abolish the salary cap and floor, introduce a player pension, and allow an agent system. Looking back now, they were completely reasonable proposals. But the clubs resisted, and the media denounced him: “How can a player earning hundreds of millions talk about unions?” Public opinion was cold. Choi was not alone. He sought legal counsel through acquaintances and also turned to Jae-in Moon, who was working as a labor lawyer in Busan at the time. Though he would later become President of South Korea, back then he was a young lawyer defending workers’ rights. This scene shows how unfamiliar and even dangerous the idea of “players are workers too” was in Korean society at the time.

However, without institutional support, the attempt could not last long. The price was harsh. He was traded overnight, from the symbol of Busan to Samsung. Everyone knew it was retaliatory, but there was no official explanation. Later he said, “Players are workers too. But I was too far ahead of my time.” His challenge ended in frustration, but it was the first voice ever raised in Korean baseball. Just as Curt Flood fought a lonely battle against the reserve clause in MLB, Dong-won Choi planted the seed in Korea.

The Players’ Association: From Frustration and Turmoil to Recognition

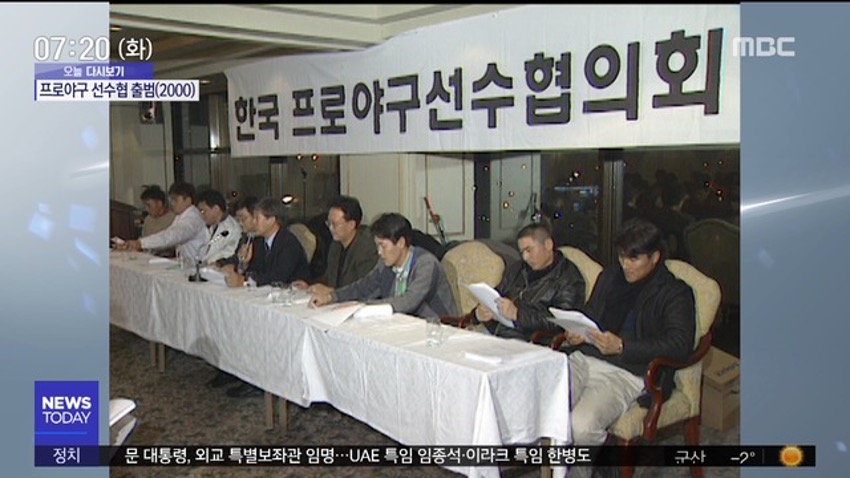

The seed planted by Choi did not die out. In the 1990s, Dong-yeol Sun and Sang-hoon Lee attempted to reestablish a players’ association. But faced with the wall of the clubs and the absence of legal structures, they ultimately failed. Still, traces remained, the growing recognition that “rights can be discussed.” In the winter of 1999, stars including Jun-hyuk Yang took the lead. The movement to form a players’ association led to the inaugural general meeting in early 2000, but due to lack of preparation and internal conflict, it fell into chaos. The KBO declared it would release as many as 75 players to stop the movement. The secretary-general at the time even said in an interview, “The league will function without those players.” But such pressure only backfired. Player rights were no longer an internal issue but a matter of public debate.

The second attempt, made after the 2000 season, was different. They emphasized procedure and strengthened internal representation. The first president was Jin-woo Song, a veteran pitcher from Hanwha. He is the all-time wins leader in Korean professional baseball. The fact that such a legend stood at the forefront showed that the players’ association was no longer just a minority voice but an institution representing the entire league. With the support of civil society and public opinion, the players’ association was finally recognized by the KBO in January 2001.

But recognition did not mean stability. Core players such as Jun-hyuk Yang, Hae-young Ma, Jung-soo Shim, and Ik-sung Choi had to endure retaliatory trades and disadvantages. The history of player rights in Korean baseball is one of institutional recognition accompanied by simultaneous suppression. In 2009, six players from Hyundai Unicorns were declared free agents for participating in players’ association activities. This time, even players who had not been involved in the association sent letters of protest to media outlets. “This is too much.” The issue of rights grew from the concern of a few to that of the entire community.

This scene overlaps with MLB history. In the 1960s and 1970s, when Marvin Miller led the MLBPA as its first full-time executive director, it was the same. His leadership earned the trust of the players, and through strikes and negotiations he secured collective bargaining rights. The moment Jin-woo Song became the face of the Korean players’ association resembles the moment in the United States when Miller brought the MLBPA into the institutional mainstream.

Player Protection: Voices Rise Again

Ik-sung Choi was one of the players who stood at the very front during the establishment of the players’ association. But the cost was severe. Due to a retaliatory trade, he had to leave his team overnight. Though he continued playing through frustration, he eventually retired. Many players, bearing similar wounds, chose silence, but he kept speaking. Even after retirement, he did not stop. He founded the Sports Athlete Protection Research Institute and in 2024 held Korea’s first-ever Player Protection Forum. Active players like Kyung-min Heo of Doosan and Young-pyo Ko of KT stood on stage alongside retired players such as Soo-chang Shim and Dae-eun Lee. It was also symbolic that the players’ association and the retired players’ association participated together. In the past, such a coalition would have been unthinkable.

At the forum, topics such as injury compensation, post-retirement life, and the power imbalance between clubs and players were openly discussed. These were once conversations reserved for barrooms, but now they were addressed in institutional language before the media and the fans. MLB fans would find this scene familiar as well. When Curt Flood fought against the reserve clause, he was completely isolated. But his sacrifice became the starting point for major league free agency, and Marvin Miller institutionalized it through the MLBPA. The way Ik-sung Choi expanded his personal wounds into intergenerational and collective solidarity through the forum after retirement mirrors that very process.

And he did not stop. Through the institute he established, he also joined hands with the Korean Professional Football Players Association, expanding solidarity beyond baseball to other sports.

The Message Left for Korean Baseball

The protection of player rights in Korean baseball started late and has followed a difficult path. The challenge of Dong-won Choi against club abuse of power, the collective strength that brought the players’ association into the institutional sphere, and the return of Ik-sung Choi who organized Korea’s first Player Protection Forum, all these steps have formed today’s movement.

Yet even now in Korea, players are often seen not as “workers” but as “independent contractors.” Criticism persists over whether well-paid stars have the right to speak of rights. But the essence of rights is not about income level. The right to be respected in the workplace and to safeguard one’s body and future safely is not determined by salary scale.

The message of Korean baseball is clear: players are workers and human beings deserving of respect. Rights do not emerge on their own. They take root only through sacrifice, solidarity, and the empathy of society. The journey for rights in Korean baseball continues to this day.

Leave a comment