by Keith Spalding Robbins

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Keith Spalding Robbins examines a little-known amateur tour from 1935.

“Last year in the Guide it was the pleasure of the editor to call attention to the fact that the Japanese had so thoroughly grasped Base Ball that they were bent on some day playing an American team for the international championship.” So proclaimed John Foster in the 1913 Spalding’s Guide. That anticipated “some day” finally arrived in November of 1935; that “American team” was the Wheaties All-Americans. The nascent beginnings of the hoped-for “international championship” series participants were the Wheaties All-Americans and Tokyo’s best amateurteams.

The 1935 Wheaties All-Americans were not just a team, but part of a multi-year effort to create a global sports organization. The team was the brainchild of Leslie “Les” Mann, a former major-league player who became a college coach and leading organizer and promoter of amateur baseball. Mann wanted to make baseball an Olympic sport and to create organized international competition. But first the European- based Olympic Committee had to be convinced that the American national pastime would be appropriate for their global games.

Given the complex requirements established by the International Olympic Committee, it took Mann five years to create the new necessary domestic and international amateur baseball organizations to push his plan forward. By 1935 he had the pieces in place to stage an amateur baseball exhibition in Tokyo “to encourage Japan to form an amateur organization … for participation in [an] Olympic Baseball championship,” and to show Olympic officials that baseball was a viable and legitimate international sport. The 1935 Wheaties All-Americans were trailblazers on a global goodwill baseball mission—to bring baseball to the Olympic Games.

THE GREAT FINANCIAL CHALLENGE

Initially, Mann had promises of financial support from the major leagues, and the A.G. Spalding & Bros, firm. As the Great Depression wore on and corporate profits declined, that support waned. Needing more financial resources for the expensive transpacific journey, Mann went looking outside the traditional sports funding sources, and found General Mills. Thus, the team was dramatically introduced to the American public by Wheaties Cereal on the Jack Armstrong, All American Boy radio show. This amateur ballclub was known as the 1935 Wheaties All-Americans.

UNEASE WITH COMMERCIAL SPONSORSHIP NAME

The Minneapolis cereal producer subsidized the trip for $12,000, and the “Wheaties” name was prominently displayed on the left sleeve of the players’ uniform. Yet the name “Wheaties” is not listed in many sources describing the team. The Japanese Olympic committee objected to the name as a symbol of the commercial corruption of amateur sport.The Japan Advertiser and the Japan Times & Mail, for example, did not use the Wheaties name when referring to the team, yet the Honolulu Advertiser called it by its Wheaties moniker.

SELECTING THE TEAM

With his trademark bravado, Les Mann announced that the final player selections were taken from a baseball talent pool of 500,000 to 1 million American youths. To narrow the pool, Mann and General Mills created a contest. Consumers could nominate an amateur player by writing his name on a Wheaties box top and mailing it to Mann. Players with the most box-top votes would be given a tryout. Some 1,000 players were nominated out of the countless thousands of Wheaties breakfast cereal box tops submitted. This list was narrowed down to a final 100, who were then reviewed by trusted scouts and a selection committee. Other players were added to the list through recommendations of top collegiate and amateur coaches. Forty players were then selected to the first and second teams and announced in newspapers in the fall of 1935. The final candidates for the Japan trip were announced nationally in late September. This was the first nationally selected amateur baseball All-American team.

THE 1935 WHEATIES ALL-AMERICANS

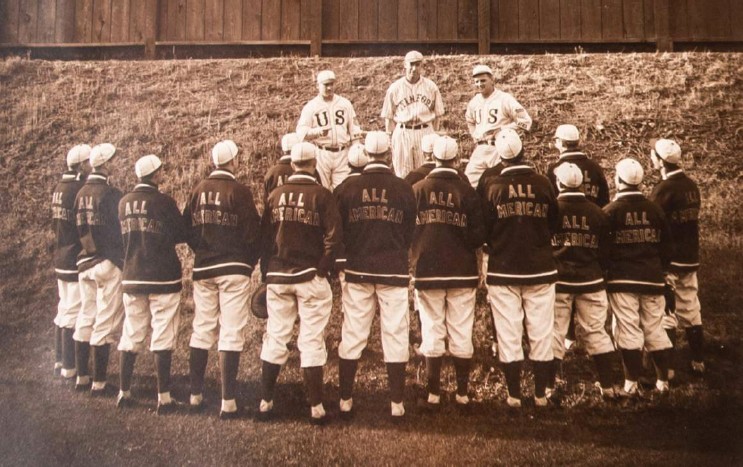

The final team included 16 ballplayers: pitchers George Adams (Colorado State University), Lou Briganti (Textile High School, Manhattan), George Simons (University of Pennsylvania), Hayes Pierce (Tennessee Industrial School, Nashville), and Fred Heringer (Stanford University); catchers Ty Wagner (Duke University) and Dirk Offringa (Ridgefield High School, Wyckoff, New Jersey); infielders Bob Chiado (Illinois Wesleyan College), Leslie McNeece (Fort Lauderdale High School), Alex Metti (Fisher Foods, Cleveland), Frank Scalzi (University of Alabama), Ted Wiklund (Kansas City), and Ralph Goldsmith (Illinois Wesleyan); outfielders Jeff Heath (Garfield High School, Seattle), Ron Hibbard (Western Michigan Teachers College), and Emmett “Tex” Fore (University of Texas). The manager was Max Carey and the coaches Les Mann and Herb Hunter.

The players were selected not only for their ability but also for their character to act as ambassadors during a nearly three-month-long trip to a foreign land. The team also reflected Mann’s habits of clean living and notable positive behaviors. Carey, an old-school veteran player, gruffly lamented, “Only two of them smoke, and none of ’em drink. What kind of a ball team is this?”

Briganti, McNeece, and Offringa were teenagers, and all but McNeece had graduated from high school. Metti, Pierce, Simons, and Wiklund were well-established amateur or semipro ballplayers. Wiklund’s semipro career was unique; he attended Missouri Teachers College at Warrensburg and was the starting guard for their basketball team, but the college had no baseball team. His baseball fame was generated at the local sandlot Ban Johnson Amateur League of Kansas City, where he was the league MVP. Heringer and Wagner had graduated from college that spring and kept their amateur status active. Scalzi returned to Tuscaloosa to finish his college career as a three-year starter and Alabama’s team captain, and led the club to three consecutive SEC baseball titles. Scalzi’s immortality in Alabama sports history was cemented: He was football Coach Bear Bryant’s college roommate. Wagner was the captain of coach Colby Jack Coombs’ winning Duke baseball team. Adams, Chiado, Goldsmith, Fore, and Hibbard were underclassmen ballplayers. Hibbard also had played for the Battle Creek (Michigan) Postum team against the 1935 barnstorming Dai Nippon Baseball Club. Like Babe Ruth, he too was struck out by the Japanese great Eiji Sawamura. Hibbard was the only player who had faced Japanese opposition before the trip.

The All-Americans boarded the NYK line’s passenger ship Taiyo Maru on October 17 in San Francisco, with a scheduled arrival at Yokohama on November 3. The joyous troupe posed for syndicated newspaper photos in their grand quasi-Olympic apparel. The ballplayers wore white buck shoes, white dress pants, white shirts, red neckties, red sweater-vests, and resplendent and elegant dark blue baseball sweaters. The embossed logo was Art Deco-inspired, with giant USA letters and an eagle emblem atop a red and white shield. Adding to the ensemble, all the players wore the now-traditional USA signature Olympic beret. Honoring their bat sponsor, many were holding their Louisville Sluggers high.

JAPANESE TOURISTS

Once in Japan, the ballplayers were given the special tourist treatment and were well feted. Staying at the historic Imperial Hotel, they attended private receptions at the Pan-Pacific Club, the US Embassy, and the Japanese government’s Education Department. Iesato Tokugawa, a member of the Japanese royal family and chairman of the 1940 Japanese Olympic Committee, sponsored a banquet for the American baseball tourists. Bob Chiado and his Illinois collegiate teammate, Ralph Goldsmith, were overwhelmed by the authentic Japanese cuisine experience. Writing back to his hometown newspaper, Chiado remarked:

They say that [the sukiyaki’s] aroma is a great appetizer for it is said to be a mixture of all those best kitchen smells which excite the salivary glands and thus make the mouth water but neither Ralph nor I could eat it. … [A]bout all we could do was to eat the rice, and the dessert, which was persimmons. … The main feature of the suki yaki dinner is a large fish, done up artistically. At this time, we were using chop sticks and sitting on the floor. After this came some raw fish, and some more fish, and “Goldie” and I were happy when the party was over.

In typical first-time tourist behavior, the more sushi the mid-westerners saw and were offered, the more they became homesick. The lumbering first baseman and football player lamented, “I will still stick to those big T-bone steaks.”

Chiado overcame his fear of raw fish to enjoy and admire Japanese architecture, the scenic mountainous landscape, and the island nation’s unique cultural and historic sites. The team traveled north to the Kinugawa Onsen and spent the night in Nikko. “We lived native for the night here, all sleeping on the floor, in keeping with an old Japanese custom” on traditional tatami mats, Chiado noted with a tourist’s pride of accomplishment. The team visited the famous Dawn Gate, the Sacred Stable, and the famous vermillion-lacquered bridge at the Futarasan-jinja shrine. Then the team hiked through the snow to the mountain peaks. Overwhelmed with the scenic views of the numerous majestic waterfalls, Chiado wrote back home glowingly, “The Nikko Shrine is probably the most beautiful sight in Japan, if not the world.”

Some of the baseball tourists carried with them letters of introduction to selected Japanese officials and industry leaders. New Jersey’s Dirk Offringa carried a letter of introduction from the governor of New Jersey to certain dignitaries in Tokyo. The letter allowed Offringa to create a collection of souvenirs that made him a popular presenter when he returned to New Jersey.

Back in Tokyo, the intrepid Midwestern tourist/ reporter Chiado found city life modern and familiar. Chiado noted the abundance of both taxicabs and bicycles, including specialized department-store delivery bicycles darting throughout the Japanese metropolis. He noted how expensive individual automobile ownership was due to high gas prices and taxes and that Tokyo streets were overflowing with thousands of taxis. Chiado reported on up-to-date Tokyo, which had “all the modern devices and equipment of any of our leading cities and compares favorably with Chicago.”

Being college athletes, they were keenly observant of their opponents. The Japanese college experience was six years, not the United States’ traditional four years. Unlike the small-town, coed Illinois Wesleyan where he played, Chiado noted that all the opponents came from male-only urban universities with student bodies of 10,000-plus. Being a starter on the baseball team as an underclassman, Chiado was taken aback by the Japanese seniority system. He remarked, “[E]ven if a freshman was a stronger player in Japan, than a four-year man, he would not play because of seniority.” Chiado noted with some envy that Japanese baseball players received preferential and exceptional collegiate athletic treatment, “The college teams all have special houses to live in and are not scattered about campus … as are our boys.”

Witnessing how the game was played in Japan with an air of respectful honor, Chiado wrote, “They are a jump ahead of us certainly as to sportsmanship.” Ever respectful of the experience, Chiado concluded that the Japanese baseball tourist experience was both “a marvelous trip” and educational, commenting, “We have learned a great deal.”

HIGHLY SKILLED EXHIBITIONS

By 1935, Tokyo’s Big Six Collegiate Baseball League teams had played many American college teams and beaten them handily. In March of 1935, the Harvard nine’s lack of performance was described as “[t]he least said … the better. … [T]hey underestimated the strength of the Japanese collegians.” In August, Yale’s varsity nine faced the same fate. The Elis’ baseball coach, former big-leaguer Smoky Joe Wood, remarked pensively, “I know exactly what the Japanese college teams can do. … [T]hey are mighty tough. … [I]f we are lucky enough to win half our games, I shall consider the trip a success.” Yale was not lucky, going 4-6-1.

Beating the Big Six teams and capturing the favor of a smart, rabid Japanese baseball fan would be challenging, a Ruthian task. Chiado remarked that manager Mann and coaches Carey and Hunter stressed the serious nature of the trip and noted that the 1935 Wheaties All-Americans “were not out for ajoyride.” Much was at stake, as the Wheaties All-Americans vs. Japanese Big Six Series would determine the unofficial amateur champion of the baseball world. Moreover, a successful tour would help persuade the Japanese authorities tojoin the 1936 Olympic baseball exhibition game in Berlin and to establish future tournaments, fulfilling Les Mann’s Olympic baseball ambitions.

DIFFERENT BASEBALL APPROACHES

The series presented a test of different baseball philosophies. Japanese teams were noted for playing a “small ball” offensive game, while the American approach focused more on power hitting. Japanese batters were noted for their keen understanding of the strike zone, being aware of game situations, employing bunts, and hitting behind the runners as needed. Hayes Pierce noted that his fellow pitchers were pressured when runners got on, since “the first thing they think of when they get on base is to steal.” But Max Carey, had who led the National League in stolen bases in 10 seasons, was not impressed, stating in US papers that the Japanese players were not as fast as perceived.

BASEBALL AS METAPHOR

Japanese national pride in achieving parity with the United States on both the baseball diamond and high seas was a driving force in 1935. In his articles, Chiado observed, “When a Japanese boy plays against an American, he has his country at heart, and wins for his country.” In November, as the Wheaties All- Americans played the Big Six colleges on the Meiji Jingu diamond, British, American, and Japanese diplomats were preparing their governments’ positions on naval strength for the 1935 London Naval Conference. The British and American position called for a weaker Japanese naval ship ratio of 10:10:7, while the Japanese position sought parity and no quotas. Chiado concluded: “Every time a Japanese nine beats an American team, the natives feel that it is just like winning a war.”

THE BALLGAMES

The All-Americans had five days to regain their legs from three weeks at sea, practice, and do some sightseeing before their first game. They wound up playing just eight games, after some scheduled games were rained out. All the games were played during the day, which allowed time for banquets and sightseeing and helped avoid the November cold.

ontinue to read the full article on the SABR website

Leave a comment