by Dennis Snelling

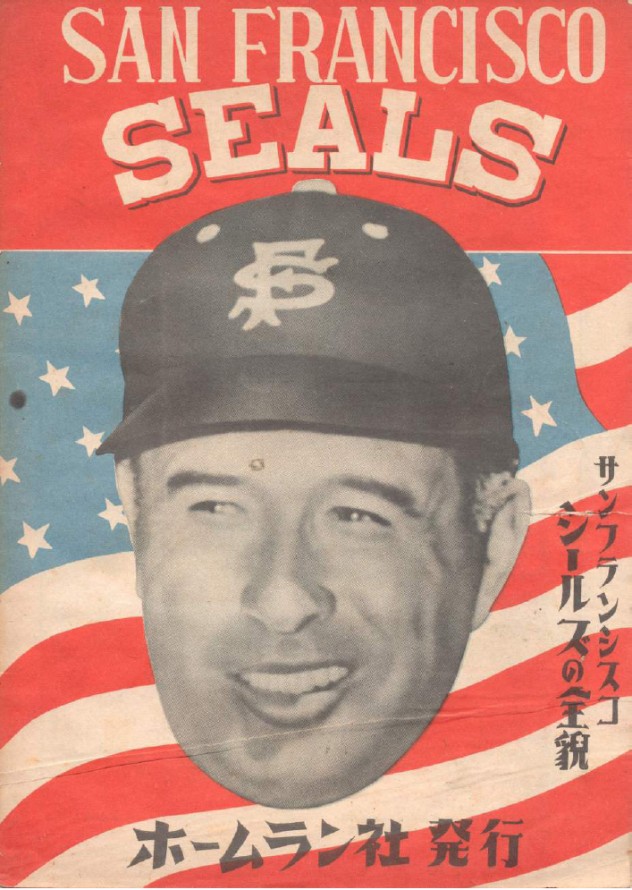

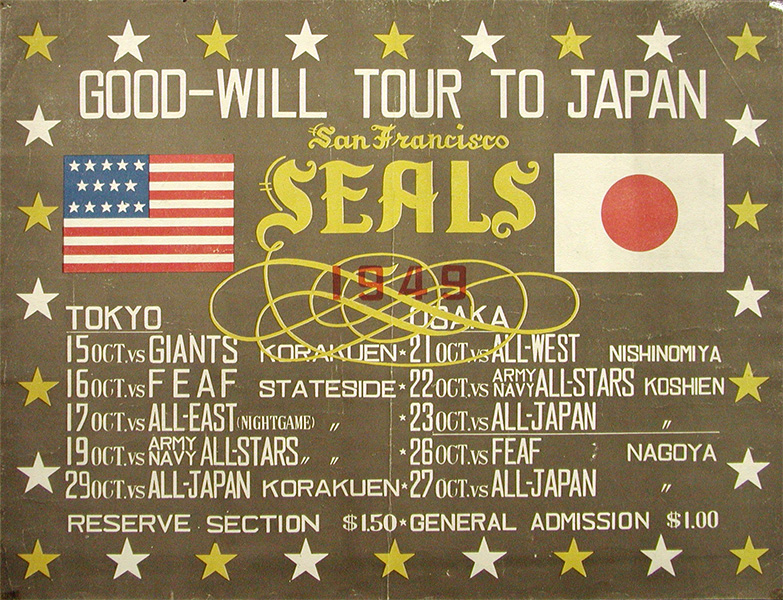

Every Tuesday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Dennis Snelling focuses on one of the most important pieces of baseball diplomacy in history: the 1949 San Francisco Seals tour of Japan

There are moments, sometimes fleeting, often accidental, when sport transcends mere athletic competition. These moments are not judged by wins or losses, nor by runs scored or surrendered. The baseball tour of Japan undertaken by Lefty O’Doul and his San Francisco Seals in October 1949 serves as a prime example—an event that changed the course of history.

At the tour’s conclusion, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, declared, “This trip is the greatest piece of diplomacy ever. All the diplomats put together would not have been able to do this.”

In a letter supporting a campaign aimed at Lefty O’Doul gaining membership in the National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, MacArthur’s successor, General Matthew Ridgway, wrote, “Words cannot describe Lefty’s wonderful contributions, through baseball, to the postwar rebuilding effort.”

In September 1945, a month after Japan’s surrender, reporter Harry Brundidge landed in the country and was barraged with queries about O’Doul. Lefty’s old friend Sotaro Suzuki, who first met O’Doul in New York in 1928 and was instrumental in organizing the 1934 tour featuring Babe Ruth, wanted Lefty to know he was okay. Emperor Hirohito’s brother inquired about the San Francisco ballplayer. Prince Fumimaro Konoe, the former prime minister of Japan, told Brundidge that O’Doul should have been a diplomat.

If the 1934 tour was a watershed moment in the history of baseball between the United States and Japan, then 1949 served as a bookend, providing a yardstick for the Japanese after they had been shut off from the rest of the baseball world for 13 years. And, while he is not enshrined in Cooperstown, the 1949 tour is a major reason that Lefty O’Doul is in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame.

Immediately after the end of the war, Douglas MacArthur was tasked with maintaining order in an occupied Japan, while at the same time maintaining the morale of its citizens. Communists were gaining a foothold, taking advantage of everyday Japanese life that was harsh, plagued with shortages of food, housing, and other basic necessities. Ruins and rubble pockmarked the country’s major cities, and families were disrupted by severe illness and death. Orphans hustled on the streets to survive, bullied, abused, and used; most of them homeless because existing orphanages could accommodate—at best—one-tenth of the need. Those who did make it into orphanages were sometimes stripped of their clothing in winter to prevent their escape.

MacArthur saw sports as a means to boost the spirit of the Japanese, and assigned General William Marquat and his aide-de-camp, a California-born Japanese American named Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, to rebuild athletic facilities around the country. University and professional baseball soon flourished, and in 1948 the amateur game was boosted through an affiliation with the National Baseball Congress, which served as an umbrella organization for semi-pro baseball in the United States and was expanding its reach to other countries. Within two years a Japanese team, All-Kanebo, was hosting a team from Fort Wayne, Indiana, in a well-received “Inter-Hemisphere Series,” won by Fort Wayne in five games.

While local baseball remained extremely popular, it was not enough to arrest the decline in morale, leading MacArthur to grill his aides about the deteriorating situation. The story goes that Cappy Harada proposed an American baseball tour, recalling the one that had brought Babe Ruth to Japan 15 years earlier. He further suggested minor-league manager and two-time National League batting champion Lefty O’Doul, widely considered the most popular living American player by the Japanese, as the man to lead such a mission.

MacArthur reportedly replied, “What are you waiting for?”

O’Doul had spent three years pushing for just such a tour and was indeed interested. In March 1949 General Marquat announced that he was deciding between two proposals, one involving O’Doul and his PCL San Francisco Seals, and the other Bob Feller and his All-Stars.

O’Doul enthusiastically made his pitch, declaring, “I think we can contribute something to postwar Japan.” While his plan involved minor-league players versus Feller’s big leaguers, the veteran manager held an advantage due to his popularity and willingness to play for expenses only. He lobbied Marquat to choose his proposition over Feller’s, arguing, “A well-trained team which has been playing together all season doubtless could demonstrate much more than a group of all-stars who had been on different teams all season.”

Marquat agreed, and in July 1949, Seals general manager Charlie Graham Jr. arrived in Japan to finalize what was hoped to be a 22-game tour beginning in mid-October.

Graham was quoted as saying that General MacArthur told him, “The arrival of the Seals in Japan would be one of the biggest things that has happened to the country since the war.” Graham said that the General added, “It takes athletic competition to put away the hatred of war and it would be a great event for Japan politically, economically, and every other way.”

Lefty O’Doul had visited Japan more than a half-dozen times by 1949, highlighted by trips while still an active player in 1931 and 1934, the latter of which led to an opportunity for him to play a role in establishing the first successful Japanese professional team, the Tokyo Giants. He had even helped that team stage two tours of the United States, in 1935 and 1936.

Now, 15 seasons into managing the San Francisco Seals, O’Doul was on a plane in October 1949 bound for Japan. There was some disappointment that for financial reasons the schedule had been pared to 10 games, but O’Doul couldn’t help experiencing an emotional mix of excitement and anxiety, reflecting the gravity of the moment.

Even so, he and his players were unprepared for the reception that awaited. The motorcade, led from Shimbashi Station by the Metropolitan Police band, was greeted by, according to some accounts, nearly one million people lining a route that stretched five miles. By all accounts, it was the largest gathering in Japan since the end of the war.

The players were astounded by the reception. “It got the boys off on the right foot,” crowed an enthusiastic Seals owner Paul Fagan. Charlie Graham Jr. sputtered, “I couldn’t believe it. Never have we seen such a demonstration anywhere.” Infielder Dario Lodigiani exclaimed, “You would have thought we were kings.”

As the 22-vehicle caravan wound through the streets of downtown Tokyo, the players were nearly obscured by a five-color flurry of confetti flung from office windows while they attempted to navigate a sea of humanity pinching the thoroughfare, fans close enough for the players to shake hands, and even sign a few autograph books. O’Doul shouted above the din, “This is the greatest ever!”

It was at this point O’Doul realized that when he greeted those along the route with a triumphant “banzai,” it was not returned.

“I noticed how sad the Japanese people were,” recalled O’Doul during an interview nearly 20 years later. “When we were there in ’31 and ’34, people were waving Japanese and American flags and shouting ‘banzai, banzai.’ This time, no banzais. I was yelling ‘Banzai’, but the Japanese just looked at me.”

O’Doul asked Cappy Harada, “How come they don’t yell banzai?” Harada replied, “That’s the reason you’re here, Lefty. To build up the morale so that they will yell ‘banzai’ again.”

The players spent their second day in Japan as a guest of Douglas MacArthur, highlighted by a luncheon served at the general’s home. MacArthur made a few remarks acknowledging the undertaking, and reminded the athletes of the importance he placed on the tour. He then turned to O’Doul and, noting his dozen-year absence from the country and the esteem in which he was held by Japanese baseball fans, told the Seals manager, “You’ve finally come home.” In public, players were treated as celebrities, provided special badges with their names printed in both English and Japanese so they would be recognized wherever they went. According to Seals outfielder Reno Cheso, every team member was assigned a car and driver, standing at the ready 24 hours a day.

The Americans were quickly exposed to the Japanese mania for baseball. There were more than two dozen magazines devoted to the sport in Tokyo alone, and the game was played everywhere, all the time. “It was nothing to see Japanese kids playing ball on the streets and in vacant lots as early as six o’clock in the morning,” noted Dario Lodigiani—without revealing whether he was witnessing this as he was rising for the day, or as he was crawling back to his hotel following a raucous night.

And then there were the autograph seekers—none of the Seals had ever seen anything like it, O’Doul included. Bellboys served as lookouts, and when the players returned to their hotel they confronted a gauntlet of fans in the lobby, each with baseballs and autograph books at the ready.

“I remember the hordes of people who used to line up seeking Babe Ruth’s autograph when the Babe was at the height of his career,” said O’Doul. “But that was a bit more than a puddle of beseeching humanity compared to the ocean we encountered on every street comer, store, and hotel lobby in Kobe and Tokyo.”

Many were repeat customers, looping back multiple times to obtain a signature on a ball or a program. Seals owner Paul Fagan was approached by one such man for three straight mornings. When he appeared for a fourth day in a row, Fagan asked him why he wanted another autograph from him. The man cheerfully replied, “All I need is four of your signatures and I can swap them for one of O’Doul’s!”

The evening after lunch with MacArthur, O’Doul quashed a potential rumble at the Tokyo Sports Center, during a rally held in the team’s honor. People had lined up for nine hours in anticipation of gaining admittance; while 15,000 successfully obtained a coveted seat, 2,000 more remained outside, frustrated when the doors were locked.

Made aware of the situation, which threatened to turn ugly, O’Doul rushed outside and apologized for not being able to admit the unlucky fans. He then told them, “I think speaking to you personally will no doubt serve to promote goodwill and friendship.” The crowd peacefully dispersed.

The day before the first game, following a two- hour workout that included his taking a few swings, O’Doul made it clear that the Seals would respect their opponents. “In order to show our gratitude,” he said, “we intend to fight to the best of our ability and win the first goodwill game with the Giants with our best members.”

The manager of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, Osamu Mihara—who had broken O’Doul’s ribs in a collision at first base during the 1931 tour—also vowed to use his best lineup, with one exception; his starting pitcher would be Tokuji Kawasaki, arguably the team’s third- best hurler. Mihara gambled that Kawasaki’s unusual breaking pitches would surprise the Americans. Since this would be the only meeting between the Seals and the team O’Doul had helped launch, Mihara’s choice disappointed many Japanese commentators, who had wanted to measure how their best professional team matched up against O’Doul’s squad.

Fifty-five thousand fans jammed Korakuen Stadium for the tour’s first contest—the largest crowd ever to attend a game there. The stands were packed three hours before the first pitch despite a steady drizzle that had threatened cancellation.

O’Doul addressed the fans before the game began, and the crowd roared its approval when he began his speech with a single word—a word he knew they would appreciate. The word was, “Tadaima,” translated in English as “I am home.”

He presented a dozen American bats to each manager of the Japanese professional teams, and received thanks from the Japanese chairman of the event, Frank Matsumoto. Cappy Harada then introduced the Seals players to the crowd, and Mrs. Douglas MacArthur threw the ceremonial first ball to Seals pitcher Con Dempsey.

Controversy would not absent itself from this event. The Japanese were surprised—and thrilled—when the national anthems of both nations were played and their flags flew together, the first such instance since the war. In contrast to the deep emotional response of the crowd, some in the American military contingent were angered by the display.

Cappy Harada then ignited a firestorm by saluting both flags, a gesture that did not go unnoticed by the crowd. That salute, coming from a Japanese American no less, further infuriated some of Harada’s fellow American officers, who wanted him punished immediately. Complaints reached General MacArthur, who quashed the objections by revealing that he not only approved, but had asked Harada to do it, and Harada continued to do so for the remainder of the tour. O’Doul was pleased by the raising of the flags, and reflected on the emotion of that day. “I looked at the Japanese players and fans,” he remembered nearly two decades later. “Tears. [Their eyes] were wet with tears. Later, somebody told me my eyes weren’t too dry either.”

The Seals easily won the opener, 13-4, even though San Francisco starter Con Dempsey was less than sharp, having been idle for three weeks. The 52-year- old O’Doul, energized by his return to Japan, grabbed a bat in the eighth and grounded out as a pinch-hitter. Pittsburgh Pirates left-hander Bill Werle, a former Seal added to the roster because several of the current Seals could not make the trip, relieved Dempsey and hit two batters in the fifth, but settled down and struck out the side the next inning. Werle closed the game with a one- two-three ninth, a pair of strikeouts and a slow roller to the mound. Werle’s opposite, Kawasaki—chosen because Osamu Mihara thought he would prove more effective against the Seals lineup—failed to make it out of the first inning. Afterward, Kawasaki blamed his underwhelming performance on the American horsehide baseballs that were used, complaining that they were more slippery than the cowhide baseball normally employed by the Japanese.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

Leave a comment