by Roberta Newman

Every Monday morning we will post an article from SABR’s award-winning books Nichibei Yakyu: Volumes I and II. Each will present a different chapter in the long history of US-Japan baseball relations. This week Roberta Newman highlights the New York Yankees 1955 tour of Japan.

On Thursday, October 20, 1955, the New York Yankees and their entourage landed at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport to begin a three-week, 16-game goodwill tour of Japan. There, they were mobbed by kimono-clad young women bearing bouquets, an eager press corps, and a thousand devoted fans. The result was chaos, as children, autograph seekers,joumalists, businessmen, and advertisers of all stripes besieged the Yankees party. But the airport crowd was tiny compared with the throng lining the streets of Tokyo. An estimated 100,000 turned out to shower the motorcade—23 vehicles carrying the players and coaching staff, team co-owner Del Webb, general manager George Weiss, Commissioner Ford Frick, and accompanying wives—with confetti and ticker tape. They were also showered with rain from Typhoon Opal, but the weather, which caused significant damage and loss of life elsewhere in Japan, did little to dampen the crowd’s enthusiasm.

The Yankees were not the only American visitors to arrive in Japan on that day. Former New York Governor and failed presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey also landed in Tokyo on the Japanese leg of his world tour, with the stated aim of learning about Japan’s recent economic advances. In reality, Dewey’s aim was to spread pro-American Cold War propaganda to a new democracy still finding its political direction, a nation he called “one of the keystones to any sound system of freedom.” Dewey stayed but four days, his visit gamering little coverage in the English- language press. In contrast, the Yankees remained in the spotlight and on the pages of newspapers for the entirety of their visit. If influence can be measured by column inches, the Yankees’ impact on Japanese attitudes toward America far outweighed that of the political power broker.

Ten years before the Yankees arrived, Japan was thoroughly beaten, exhausted from fighting the “Emperor’s holy war.” Of the early postwar period, historian John W. Dower writes:

Virtually all that would take place in the several years that followed unfolded against this background of crushing defeat. Despair took root and flourished in such a milieu; so did cynicism and opportunism—as well as marvelous expressions of resilience, creativity, and idealism of a sort possible only among people who have seen an old world destroyed and are being forced to imagine a new one.

For the Japan that greeted the Yankees, this new world had just begun to become a reality. The year 1955—Showa 30 or the 30th year of Emperor Hirohito’s reign by the Japanese dating system—marked the beginning of what would be called the Japanese Miracle, a period of unprecedented economic growth that lasted more than three decades. Ironically, war was the engine that drove the Japanese Miracle—the Cold War. In 1945, Japanese industry was crippled—almost one-third of its capacity had been demolished. With staggering unemployment rates among an educated labor force, combined with the country’s advantageous geographic location near Korea, China, and the USSR, Japan became an ideal place to establish new war-related industries and revive old ones. In a very real sense, Japanese manufacturers played an active part of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower would come to call the “military-industrial complex” in his 1961 farewell speech. Nevertheless, in 1955, relations between the United States and Japan were occasionally tense, the United States fearing that Japan, like India, would take a neutral position in the power struggle between it and the Soviet Union. It did not. Instead, it became one of the United States’s strongest allies. But the strength of that alliance was still wobbly as the two nations negotiated an ultimately successful trade deal, one that would see Japan’s entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and become a player in the global economy.

Though clearly not as delicate as treaty talks with international implications, negotiations to bring the Yankees to Japan were handled with care. In a very broad sense, these negotiations were a microcosm of the larger, far more complicated economic and political talks. In June, during the broadcast of a “good will talk” for the Voice of America, Yankees manager Casey Stengel, who had toured Japan in 1922 as part of an all-star outfit, let it slip that he might be returning. An anonymous source within the Yankees intimated that the team had, in fact, been discussing the possibility of a tour, as had several other clubs. Although there may have been other teams under consideration, it had to be the Yankees. As New York World Telegram and Sunsports columnist and Sporting News contributor Dan Daniel observed, “Information from U.S. Army sources says that baseball enthusiasm over there (in Japan) and rooting support for the pennant effort of the Yankees have achieved unprecedented heights.” Daniel, who covered the New York team, became the primary source of information regarding tour negotiations, though he did not cover the tour itself. But he was not the only sportswriter to weigh in. Writing in the Nippon Times, F.N. Mike concurred, noting, “The Yankees is a magic name here, where every household not only follows baseball doings in Japan, but also that in America. The Yankees, of all others epitomizes big-time baseball in the States, just as Babe Ruth, who helped to build up its name and who led the great 1934 All-Americans to Japan, represented baseball in America individually.” And not only were the Yankees the most recognizable and most popular American team in Japan, but their very brand meant “American baseball” and, by extension, America, to the Japanese, in the most positive sense.

Before the Yankees front office would consent to the visit, it required assurance that both governments were on board. More importantly, even after they were invited to tour by sponsor Mainichi Shimbun, the second largest newspaper in Japan, the organization would not begin to plan a tour without a formal invitation from the Japanese. The Japanese government laid down certain conditions, most specifically, that the visiting team would not be compensated. According to Daniel, “the proposition offers no financial gain to the club. Nor would any of the players receive anything beyond an all-expense trip for themselves and their wives.” In fact, it was absolutely essential that the team agree to forgo any type of payment. Writing in Pacific Stars and Stripes, columnist Lee Kavetski observed, “Each Yankee player is likely to be asked to sign an acceptance of non-profit conditions before making the trip.” Kavetski continued, “It is recalled an amount of unpleasantness developed from the Giants’ 1953 tour. Upon completion of the tour, some of Leo Durocher’s players complained that they had been misled and jobbed about financial remuneration. There was absolutely no basis for the complaint. And the beef unjustly placed Japanese hosts in a bad light.” This was hardly goodwill. Indeed, it was a public-relations disaster that extended into the realm of foreign relations. Kavetski noted, “As Joe DiMaggio, who has been to Japan twice, said to New York sports writer Dan Daniel, ‘Stengel’s players can perform a great service to baseball and to international friendship if they sign up for the trip even though there is no prospect for personal financial gain.’”

Why did the bad behavior of a few American baseball players border on an international incident? On April 28, 1952, the San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed by 49 nations, including the United States and Japan, officially ended World War II. It also ended the Allied Occupation. As such, the Giants were guests in a newly sovereign nation trying to find its way and to establish its identity on a global stage. Tour sponsor Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest newspaper, promised to pay each player 60 percent of the gate of their final two games in Osaka in return for their participation. Unfortunately, the resulting figure was smaller than the players expected. Only 5,000 of the 24,000 who attended the first of those games actually bought tickets. As a result, each player was to be paid $331, in addition to “walking around money.” While this was no small amount—it translates to approximately $3,550 in 2021 dollars—it was nowhere near the $3,000 they believed they would net. Writing in Pacific Stars and Stripes, Cpl. Perry Smith noted, “The individual players did not appreciate the ‘giving away of the remaining 19,000 tickets and six team members refused to dress for the final contest.” Although they were eventually persuaded to take the field, they were not happy. This represented a significant cut in revenue for players accustomed to making good money during the offseason.

Although the players thought they had a legitimate beef, their complaints did not play well in the press. To demand more was a public insult. Conditions in Japan had certainly improved by 1953, when the Giants toured, but they were far from ideal. Poverty and unemployment were still an issue, as was Japan’s huge national debt. That representatives of a wealthy nation demanded payment from the representatives of a newly emerging nation looked especially bad. That the players themselves were no doubt viewed as wealthy by individual Japanese could not have helped, either. It was essential that the Yankees not make the same mistake, treating their hosts as inferior and not worthy of due respect.

In 1955, US-Japanese relations were still a work in progress. While arrangements for the tour were being discussed, Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu visited the United States for talks with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. At a press conference, Shigemitsu, who simultaneously served as Japan’s foreign minister, “emphasized the desire of his government for a more independent partnership with the United States.” For Japan to make what Shigemitsu called “a fresh start,” he said, “we must talk things over frankly with the United States and see that the two governments understand each other.” Of course, Shigemitsu’s conference with Dulles had nothing directly to do with the goodwill baseball tour. But as he suggested, conditions laid down by a government seeking recognition of its independence had to be given their due. And given the timing, it would have been terrible optics were the insult to be repeated.

Ultimately, the Yankee players agreed and the tour was organized, but not before another major wrinkle had to be ironed out. Once Mainichi Shimbunoffered its sponsorship, its chief competitor, Yomiuri Shimbun, countered with an offer to another team. Commissioner Frick was not having any of it. He responded negatively, announcing that simultaneous Japanese tours by two major-league clubs was out of the question—it would be one or none. Following their own delicate negotiation, competitors Mainichi and Yomiuri came to their own agreement. The two papers would sponsor tours by American clubs in alternating years.

On August 23 George Weiss announced that the visit would proceed. Beginning with five games in Hawaii and ending with several more in Okinawa and Manila, the Yankees would leave New York shortly after the World Series on October 8 and planned to return on November 18. Included in the group of 64 travelers were many of the players’ wives, though some planned to stay behind in Hawaii. Among these wives were those of Andy Carey, Eddie Robinson, and Johnny Kucks, all of whom were on their honeymoons.

The schedule, which included games in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyushu, Sendai, Sapporo, Nagoya, and Hiroshima, was announced on September 24. Tickets, which went on sale on October 1 for the Tokyo games to be played at Korakuen Stadium, ranged in price from 1,200 yen (approximately $3.33) for special reserved seats, to 300 yen (approximately 83 cents) for bleacher seating. Games at other stadiums would top out at 1,000 yen (approximately $2.77). According to Japan’s National Tax Agency, in 1955 private sector workers earned an average annual salary of 185,000 yen (approximately $513). This was a great improvement from the poverty of the early postwar years. Indeed, it was approaching twice the annual salary that private sector workers earned in 1950. But even a ticket to the bleachers would have been a considerable reach for the average worker. As a result, it is safe to assume that the live spectatorship for the Yankees games would have consisted primarily of well-off Japanese as well as American servicemen. Other Japanese fans had to make do with newspaper coverage, radio and, in many cases, television. Realistically speaking, television receivers were extremely expensive, making individual ownership rare—in 1953, for example, even the least expensive receivers cost more than a year’s wages for the average Japanese consumer. But this didn’t mean that television was only for the wealthy. As in the United States, sets were placed strategically in front of retail establishments in order to draw customers. Far more common, however, was the institution of gaito terebi, plaza televisions, sets situated in accessible public spaces, which gave rise to the practice of communal viewing. This would have enabled many Japanese fans to watch the games.

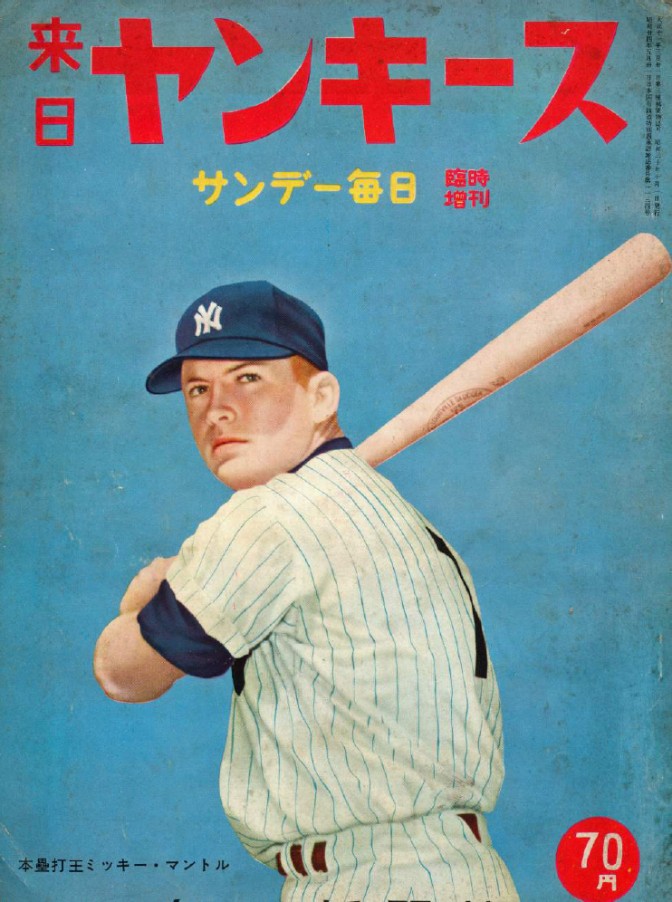

A Japanese poster promoting the series announced, “Unprecedented—the marvelous terrific team of our time—Champion of the Baseball World—New York Yankees—coming! Sixteen games in the whole country.” While not entirely accurate—the Yankees went on to lose the World Series to the Brooklyn Dodgers in seven games after the poster was printed—it did not matter to Japanese fans. Given the public response to the team’s arrival in Tokyo, the Yankees were, in fact, the “marvelous terrific team” of l955.

That the series had a purpose beyond “goodwill” was publicly stated by Vice President Nixon, speaking on behalf of President Eisenhower, on October 12. Eisenhower had, in fact, been involved with the planning, according to Del Webb. Prior to arranging the tour, Webb had discussed its potential benefits with the president, Secretary Dulles, and General Douglas MacArthur, former commander of the Allied powers in Japan. “I asked the president last summer if he thought a trip by the Yankees might help bring the American and Japanese people closer to each other,” said Webb. “He said it would.” So it was no surprise that Nixon made a statement, addressing Commissioner Frick, expressing the president’s best wishes. Nixon wrote, “Appearances in Japan by an American major league baseball team will contribute a great deal to increased mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of Japan, and thus to the cause of a just and lasting peace, which demands the continued friendship and cooperation of the nations of the Free World.” It was up to the Yankees, Nixon implied, to help cement the US-Japanese alliance, assuring that Japan would come down on the side of “freedom” rather than neutrality in the ongoing struggle against the unfree Soviet bloc. Of course, the vice president’s statement was a clear example of the inflated rhetoric of Cold War propaganda. But the message was unavoidable. Public relations played an essential role in geopolitics, and this tour was, above all else, an exercise in public relations.

Having fared well on their Hawaiian stop, winning all five games against a mixture of local teams and armed forces all-stars, and having survived their mobbing at the airport, the Yankees began their hectic schedule. The sodden but jubilant welcome was followed by a series of events, receptions, and press conferences. The next day, the team worked out while Stengel, who would serve as the face of the club, and Weiss attended a luncheon at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club. Lest it be thought that the tour consisted only of propaganda, the proceedings included their fair share of frivolous fun, which was also covered in the press. At the club, Stengel was presented with a gift—a large box, labeled “For 01’ Case.” According to the Nippon Times,“Stengel stood patiently by while bearers deposited the box at his feet. Then, lo and behold, a pretty girl in a kimono crashed through the wrapping pounding her fist into a baseball glove in the best tradition of the game.” Sensing an opportunity to get in on the act, Weiss “went through the motions of putting the girl’s name to a contract.” In what might, in twenty-first-century terms, be considered in very bad taste, Weiss asked her how much she wanted. But under the circumstances, Weiss’s actions were just part of the fun. Nevertheless, Stengel took a moment to emphasize the true nature of the tour. The Yankees were in Japan “on a serious mission of good will.”

It would be nice to say that the first game, held on Saturday, October 22, went off without a hitch. But rarely does this happen when there are so many moving parts. This time, Opal did more than just soak a parade. The typhoon caused a postponement of Game Five of the Japanese championship series between the Nankai Hawks and the Yomiuri Giants, which was scheduled to be played at Korakuen Stadium on Friday. As a result, the Yankees contest had to be moved to the evening to accommodate both games. A smaller crowd than expected—35,000, about 5,000 shy of a capacity crowd—turned out to see the Yankees make quick work of the Mainichi Orions, beating the Japanese team 10-2. After Kaoru Hatoyama, the wife of the prime minister, threw out the first pitch—the very first wife of a head of state to do so at a major-league game, exhibition or otherwise—fans and dignitaries were treated to a 10-hit barrage by the Yankees, including two home runs and a triple by rookie catcher Elston Howard. The Orions countered with seven hits, but committed a costly first-inning error in their loss. The crowd, which included Thomas E. Dewey and his wife, was not disappointed.

Baseball, however, never completely supplanted diplomacy, as Prime Minister Hatoyama greeted the Yankees, Frick, and their entourage at a reception. Among the many photo ops, one stood out. Hatoyama, having been presented with a Yankees hat by Stengel, became the first Japanese prime minister to wear a baseball cap.

Continue to read the full article on the SABR website

Leave a comment