by Thomas Love Seagull

A recent poll for a TV special saw more than 50,000 people in Japan vote for their favorite retired baseball players. 20 players emerged from a pool of 9,000. Yes, they could only vote for players who are no longer active, so you won’t see Shohei Ohtani or other current stars on this list. Which is probably smart because I’m sure Ohtani would win by default. There are, however, players who were beloved but not necessarily brilliant, and foreign stars who found success after coming to NPB. Unsurprisingly, the list leans heavily towards the past 30 years, with a few legends thrown in for good measure.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be profiling each of these players. Some of these players I know only a little about, so this will be as much a journey for me as, hopefully, it will be for you. It’ll be a mix of history, stats, and whatever interesting stories I can dig up.

For now, have a look at the list below and see how the public ranked them. I’ve included the years they played in NPB in parentheses.

20. Alex Ramirez (2001-2013); 19. Yoshinobu Takahashi (1998-2015); 18. Warren Cromartie (1984-1990), 17. Takashi Toritani (2004-2021); 16. Suguru Egawa (1979-1987); 15. Katsuya Nomura (1954-1980); 14. Tatsunori Hara (1981-1995); 13. Kazuhiro Kiyohara (1985-2008); 12. Masayuki Kakefu (1974-1988); 11. Masumi Kuwata (1986-2006); 10. Atsuya Furuta (1990-2007); 9. Randy Bass (1983-1988); 8. Daisuke Matsuzaka (1999-2006, 2015-2016, 2018-2019, 2021); 7. Tsuyoshi Shinjo (1991-2000, 2004-2006); 6. Hiromitsu Ochiai (1979-1998); 5. Hideo Nomo (1990-1994); 4. Hideki Matsui (1993-2002); 3. Shigeo Nagashima (1958-1974); 2. Sadaharu Oh (1958-1980); 1. Ichiro Suzuki (1992-2000).

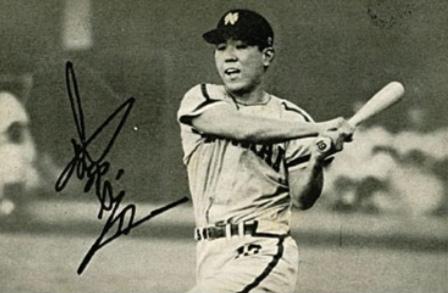

No. 15, Katsuya Nomura:

He caught nearly 3,000 games, hit 657 home runs, and never believed he was gifted

If you were playing bar trivia and the category was baseball catchers, the answers would feel obvious.

Who hit the most home runs?

Mike Piazza.

Who finished with the most hits?

Ivan “Pudge” Rodríguez.

Those are good answers. They are also incomplete.

Because in Japan, one man redefined what a catcher could be—hitting more home runs than any catcher in baseball history, winning a Triple Crown at the position, and changing how the job itself was understood.

And the irony is this: Katsuya Nomura never believed he was a natural home run hitter.

That may sound like false modesty coming from a man who hit 657 of them—more than any catcher in the history of professional baseball, second-most in Japanese history behind Sadaharu Oh—but Nomura was serious. He believed power was borrowed, not owned. Something earned through preparation, positioning, and timing, but never brute force.

He believed that if you wanted to understand baseball, you had to understand why the ball went where it did, and why people behaved the way they did under pressure.

Those beliefs did not come from theory: they came from survival.

Nomura’s father went to war when he was two years old and never came home. By three, his father was dead. What followed was not tragedy in the cinematic sense, but something quieter and more exhausting: illness, poverty, and responsibility arriving too early. His mother battled cancer—first uterine, then colon—and spent long stretches hospitalized in Kyoto. Nomura and his older brother Yoshiaki were sent to live with neighbors.

Nomura would later say that poverty itself was survivable. Even hunger was survivable. What stayed with him was learning that in someone else’s house, you could not say you were hungry at all.

When his mother finally returned, he waited for her train hours in advance at a tiny rural station surrounded by rice fields. Only a few trains passed each day. He waded into a nearby stream and chased fish to pass the time. When the train arrived, she stepped down supported by another woman, her face white, her body spent. There was no car so they borrowed a handcart, loaded her onto it, and walked home together—three people, a cart, and a future that suddenly felt very heavy.

At home, she sat silently in front of a small dresser inside their equally small room. She didn’t move and she didn’t say anything. Nomura asked what was wrong. Still, she said nothing. Only later did he understand: she was trying to figure out how to keep her children alive.

Help came from unexpected places. A local factory manager offered her work spinning yarn for carpets. Nomura learned, early, the value of kindness and the necessity of endurance. He delivered newspapers. He babysat. In summer, he sold ice candy wherever people gathered: factory lunch breaks, school fields, festivals.

Without realizing it, he was learning how information worked. If you went where people were, the ice candy sold. If you guessed wrong, it melted in your hands.

When Nomura showed promise in middle school, he aimed for high school baseball. His mother told him to abandon the idea and apprentice somewhere after graduation. It was Yoshiaki who intervened, offering to give up his own plans for college so that Katsuya could continue. Nomura never forgot that trade.

He attended a small, obscure high school—so obscure that, by his own account, they sometimes had to bring in a university student just to hit fungoes before games. Nomura was everything at once: catcher, cleanup hitter, captain, and de facto manager. They barely won. Scouts did not come. He cheated on exams to keep the team alive. He did not know what pitch calling really was. He was, in his own words, just a wall.

That turned out to be enough.

When it came time to chase baseball seriously, he did so practically. He studied the player directory and looked for teams with aging catchers. Two teams fit the bill, Nankai and Hiroshima. Nomura entered professional baseball as a test player for the Nankai Hawks, one of hundreds trying out. Seven were selected. Four were catchers, all from rural areas. Nomura didn’t understand why until later: test catchers were cheap bullpen labor and country boys were thought to be obedient. No one expected them to matter.

His first contract was ¥84,000, paid over twelve months. ¥7,000 a month. ¥3,000 went straight back to the team for dormitory fees. He only took home ¥4,000. When his hometown celebrated him as a professional player and people asked about his signing bonus, he smiled and deflected. “Use your imagination,” he said.

After his first year, having barely played, a team official told him he was being released.

Nomura went back to his dorm room, sat in the dark, and thought of home.

The next day, he returned and begged for one more year. He even offered to play for free.

The team relented and gave him another chance.

His second year nearly ended the same way. Coaches suggested he abandon catching and move to first base; his arm wasn’t strong enough to behind the plate. Nomura accepted the logic but refused the conclusion. He stayed late, throwing long toss every day in an empty stadium. For months, nothing changed.

Then one day, veteran outfielder Kazuo Horii noticed how Nomura gripped the ball.

“That’s a breaking-ball grip,” he said. “You’re a pro and you don’t know how to hold the ball? Turn the seams sideways.”

The throw changed instantly. Nomura had been teaching himself baseball from its first principles and had gotten one of the most basic ones wrong. He laughed about it later and remembered it forever.

He returned to catching because he had done the math. Beating a star first baseman was impossible. Beating a mediocre catcher was not.

He began to watch everything. How hitters reacted to pitches. How pitchers repeated mistakes. How counts shaped decisions. A former journalist working as a scorer agreed to chart pitch sequences for him. Nomura studied them obsessively. He discovered patterns where others saw randomness.

That is the version of Katsuya Nomura that explains everything that followed: the refusal to rest, the obsession with preparation, the willingness to endure being unseen. Baseball did not teach him how to survive. Baseball merely gave survival a uniform.

The numbers followed. Then the power, improbably. Nomura was never built like a slugger. He shortened his swing, widened his grip, focused on contact and rotation. “A home run that barely clears the fence counts the same,” he said.

Catching every day, hitting every day, Nomura became something Japan had never seen: a catcher who did not wear down. A catcher who hit in the middle of the order. A catcher who led the league in home runs.

During a Japan–U.S. exhibition series, Willie Mays nicknamed Nomura “Moose,” not for his size or speed, but because he stood still, watched everything, and reacted instantly when it mattered.

He moved from sixth in the order to fifth to fourth. He won batting titles as a catcher—something no one thought was supposed to happen. He led the league in home runs eight straight years. In 1965, he became the first catcher in professional baseball history to win the Triple Crown.

He thought it was terrifying. He had never believed the batting title was meant for him. He had won home run and RBI titles before, but batting average felt different. It depended too much on luck. The batting title arrived because other great hitters like Isao Harimoto and Kihachi Enomoto slumped.

Late in the season, the final obstacle was Daryl Spencer, a former big leaguer playing for the Hankyu Braves. Nankai had already clinched the pennant. Manager Kazuto Tsuruoka was away scouting for the Japan Series. Acting manager Kazuo Kageyama* pulled Nomura aside before a crucial doubleheader.

*In 1965, Tsuruoka stepped down and Nankai named Kageyama manager. Four days later, he was dead. The shock forced Tsuruoka’s return and left a lasting impression on Nomura.

“I’ll take responsibility,” he said. “Walk Spencer every time.”

Nomura hated it.

He was the catcher. He had to call those pitches. Spencer grew visibly angry, eventually holding his bat upside down in protest. Days later, before the race could resolve itself cleanly, Spencer was injured in a motorcycle accident and ruled out for the season.

When reporters congratulated him, he didn’t celebrate. He said only that he wasn’t the kind of person who could rejoice in another man’s misfortune. Later, he admitted something closer to the truth:

“If I’m the only one allowed to be this lucky,” he wondered, “is that really okay?”

He decided the only acceptable response was more work. More swings and more gratitude expressed through effort.

“I am a second-rate hitter,” he said. “That’s why I work.”

He whispered to hitters. He studied their lives. He categorized their minds. He manipulated timing and doubt. Some ignored him. Some rattled. Some fought back. Nomura accepted all of it. This was work.

He worked for 26 seasons. He was behind the plate until he was 45, catching 2,921 games. He became player-manager when he was 35. He was named MVP five times. He endured doubleheaders, summer heat, stolen bases he could no longer stop. He believed the catcher did what no one else could: give shape to baseball’s scriptless drama.

The catcher sees everything first. The catcher absorbs every mistake. The catcher makes decisions that never appear in the box score and lives with consequences that always do. When things go wrong, it is the catcher’s fault. When things go right, it is simply how the game was supposed to go.

When Nomura reached 600 home runs in 1975, the moment barely registered nationally. Nomura played for the Hawks, who played in the Pacific League, and everybody knew that what happened in the PL didn’t matter. Oh and Shigeo Nagashima were dominating headlines for the Giants in the Central League. Nomura understood. He prepared a line in advance.

“If they are sunflowers,” he said, “then I am a moonflower, blooming quietly along the Sea of Japan.”

It became his most famous quote. He even jumped rounding the bases, a rare display. The moonflower, it turned out, wanted to be seen, even if only once.

When his playing career finally ended in 1980, it happened in a way that felt fitting. With the bases loaded and his team trailing by one, Nomura was lifted for a pinch hitter. Sitting on the bench, he caught himself hoping the substitution would fail.

It did.

On the drive home, Nomura realized something unforgivable had happened: he had put himself ahead of the team. That night, he decided to retire. After all, a player who no longer put the team first had already retired in spirit.

Katsuya Nomura caught more pitches than anyone in the history of Japanese professional baseball. He endured more innings, more games, more seasons than anyone should have had to. He also grounded into more double plays than anyone in NPB history.

At his retirement ceremony, Nomura put on his catcher’s gear one last time. His teammates lined up between first and third base. One by one, they stepped onto the mound, said a few words into a microphone, and threw him a ball.

Nomura caught every one.

Nomura once said that if you take baseball away from him, nothing remains.

Zero.

But that was never quite true. Because even when the uniform came off—when the knees finally stopped cooperating, when the dugout door closed for the last time after stints of managing Yakult, Hanshin, and the newly formed Rakuten, Nomura kept doing the same thing he had always done.

He watched.

Because to Nomura, baseball was never a game solely for the gifted.

It was a game for the people who noticed.

Thomas Love Seagull’s work can be found on his Substack Baseball in Japan

Leave a comment